Rivers of India: Lifelines of a Diverse Subcontinent

Explore the rivers of India—from the sacred Ganga to the mighty Brahmaputra—shaping culture and life across the vast subcontinent.

From the icy heights of the Himalayas to the sun-drenched coasts of the Indian Ocean, the rivers of India are more than waterways—they are sacred threads weaving together landscapes, cultures, and histories. These rivers feed fields, inspire poems, cleanse souls, and shape the destiny of millions. With every bend, they whisper stories of gods and farmers, of cities born and civilizations sustained. Let’s flow with them—across geography, ecology, and time.

River of India: Geography & Geology

India’s rivers are born from the restless heart of the Earth itself—a land sculpted by ancient tectonic forces that still rumble beneath the surface. The collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates, which began over 50 million years ago, didn’t just create the towering Himalayas—it rewrote the subcontinent’s entire drainage map.

Where Mountains Meet the Sea: Asia’s Great Rivers

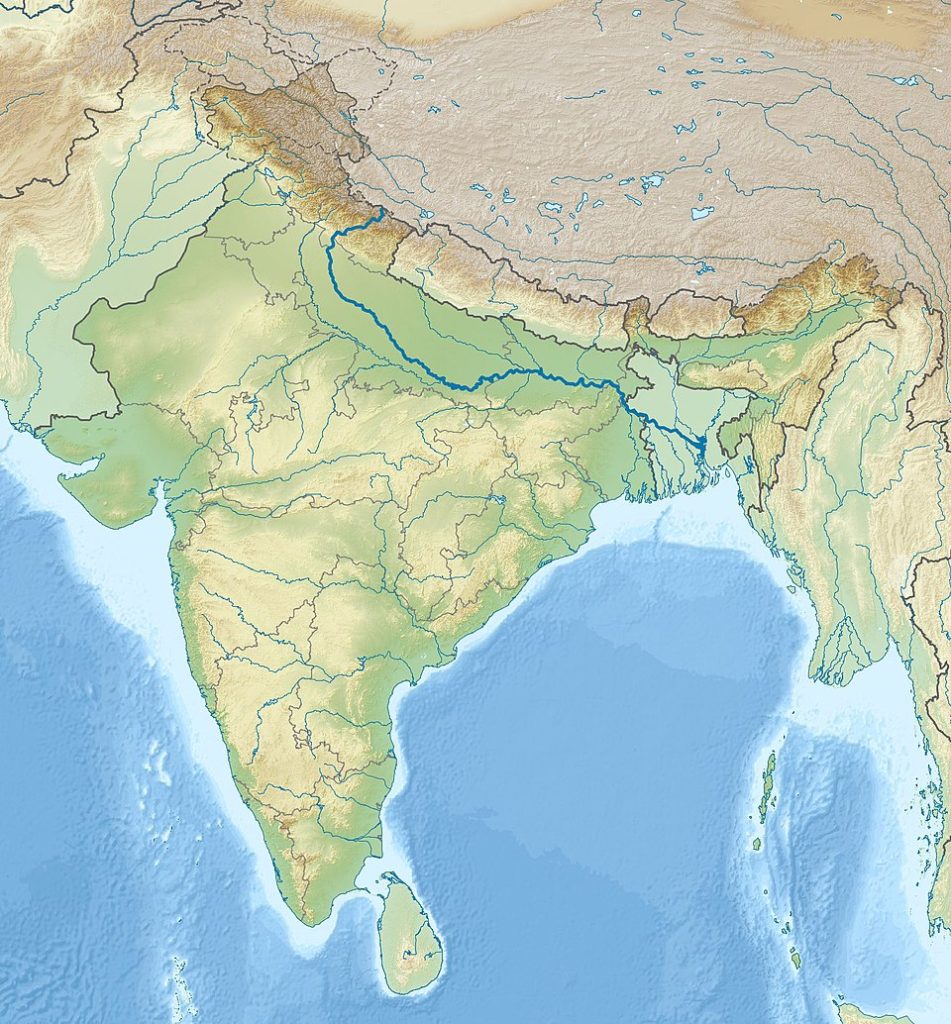

These massive mountains, still rising by a few millimeters each year, act like an enormous sponge, catching snow and monsoon rains, then slowly releasing them as perennial rivers. The Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Indus—India’s greatest rivers—originate in this Himalayan arc, coursing down with glacial vigor before meandering across the flat, fertile plains of northern India. Their enormous catchment areas support hundreds of millions of people and some of the world’s oldest civilizations.

In contrast, the Peninsular Plateau—one of the most ancient landmasses on Earth—tells a different story. Composed of hard igneous and metamorphic rocks, it lacks the dramatic uplift of the north. Here, rivers like the Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery, and Mahanadi are predominantly rain-fed. Their flow is highly seasonal, dictated by the monsoon. These rivers cut deep valleys into the plateau, creating waterfalls, gorges, and some of India’s most picturesque landscapes.

The western part of the plateau slopes gently toward the Bay of Bengal, allowing most rivers to flow eastward and form broad deltas, like the ones at the mouth of the Godavari and Krishna. However, exceptions like the Narmada and Tapi rivers defy this trend, carving out westward paths through rift valleys before emptying into the Arabian Sea.

India’s diverse topography, ranging from snowfields and foothills to plateaus, hills, and coastal plains, gives rise to a complex and rich river system. Each river, depending on its origin and the terrain it travels, follows a unique geological narrative—some calm and sinuous, others wild and untamable.

In short, the geography of India doesn’t just cradle its rivers—it commands and choreographs them, making the country’s river systems among the most varied and significant on Earth.

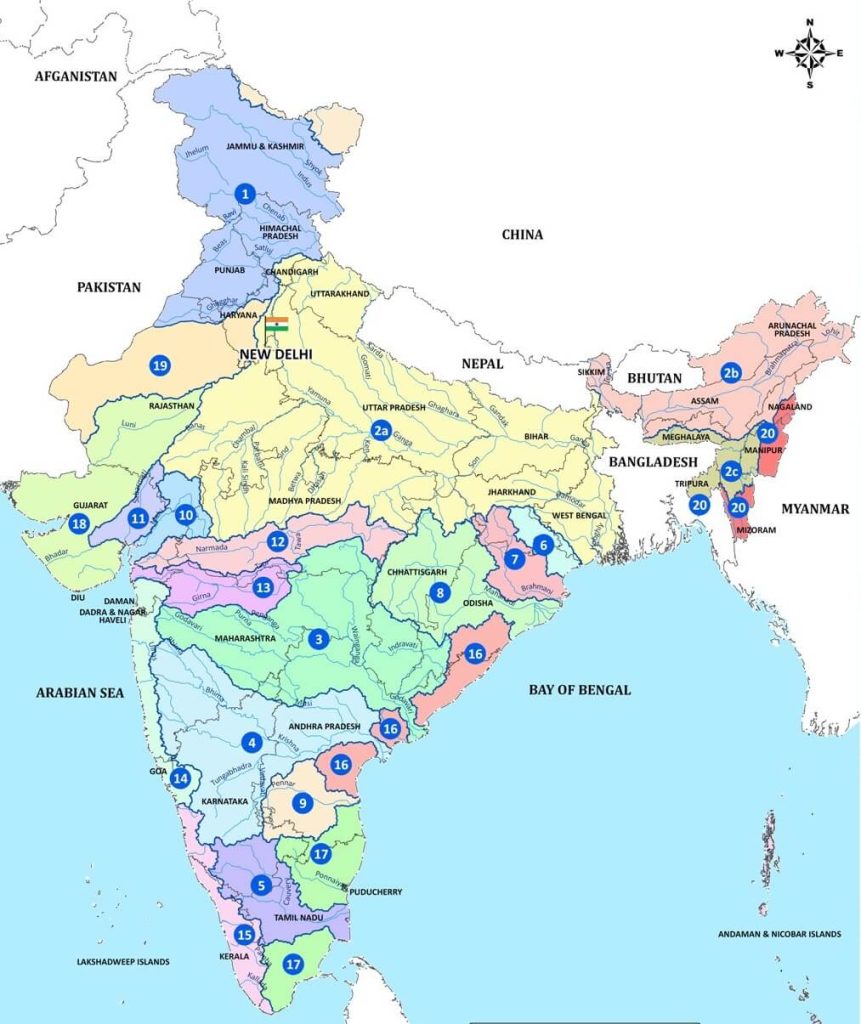

River of India: Major Drainage Basins and Catchments

India’s vast and varied landscape is etched by an intricate web of rivers, each belonging to a broader drainage basin—the geographic area from which a river and its tributaries collect water. These basins function like the vascular system of the country, channeling rain and meltwater through plains, plateaus, forests, and cities. Understanding India’s river basins is key to grasping the geography, agriculture, and cultural lifeblood of the nation.

🏔 The Himalayan Drainage System

The northern rivers—Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Indus—form the core of the Himalayan drainage system. Originating from snowfields and glaciers, these rivers are perennial, meaning they flow year-round and surge during the monsoon.

The Ganga Basin is the largest and most iconic. Stretching across northern India and parts of Nepal and Bangladesh, it covers over 1 million square kilometers—nearly 26% of India’s total land area. It is home to more than 500 million people, making it not just one of the largest, but also one of the most densely populated and agriculturally vital river basins in the world. The basin encompasses fertile floodplains, sacred ghats, and urban centers like Kanpur, Varanasi, and Kolkata.

The Brahmaputra Basin, shared with Tibet and Bangladesh, begins in the icy wilderness of the Himalayas as the Yarlung Tsangpo, then carves one of the world’s deepest gorges before entering India. It swells dramatically during monsoons, often causing widespread flooding in Assam and Bangladesh.

The Indus Basin, though now mostly in Pakistan, still waters parts of northern India through its tributaries like the Jhelum, Chenab, and Beas. Its ancient floodplains gave rise to the Indus Valley Civilization, one of the world’s oldest urban cultures.

🪨 The Peninsular Drainage System

South of the Vindhyas lies the Peninsular Plateau, one of the oldest landmasses on Earth. Rivers here, such as the Godavari, Krishna, Mahanadi, and Cauvery, arise from the highlands and flow toward the Bay of Bengal. Unlike their Himalayan cousins, these rivers are rain-fed and have highly seasonal flows, with peak discharge during the southwest monsoon.

The Godavari Basin, sometimes called the Dakshin Ganga or “Ganges of the South,” is the second-largest basin in India, covering parts of Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh.

The Krishna Basin supports extensive irrigation systems, especially in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, while the Cauvery Basin—though smaller—is agriculturally rich and politically significant due to inter-state water disputes.

The Narmada and Tapi Rivers are unique in that they flow westward, emptying into the Arabian Sea. Their basins are narrower but geologically fascinating, cutting through ancient rift valleys and gorges.

🔄 Endorheic and Coastal Basins

India also has smaller endorheic (closed) basins, like the Luni River in Rajasthan, which flows into marshlands rather than reaching the sea. Along both coasts, short and swift rivers like the Sharavati or Periyar drain the Western and Eastern Ghats, feeding lush forests and waterfalls before tumbling into the sea.

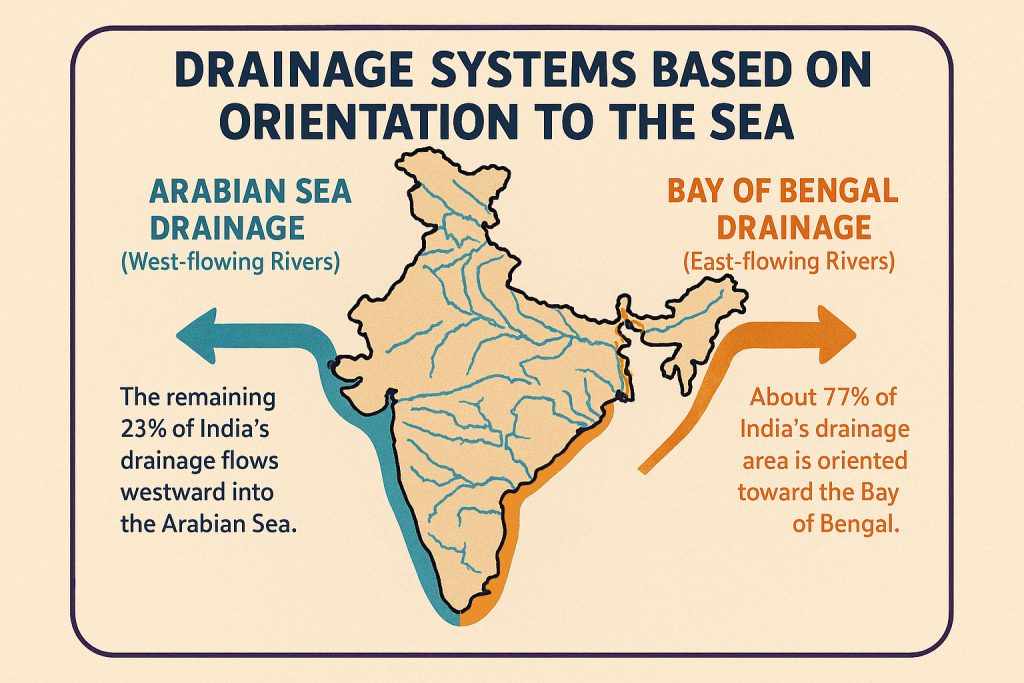

🌊 Drainage Systems Based on Orientation to the Sea

India’s rivers follow two major directions, determined by the slope of the land:

➡️ Bay of Bengal Drainage (East-flowing Rivers)

About 77% of India’s drainage area is oriented toward the Bay of Bengal.

Rivers like the Ganga, Brahmaputra, Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery, Mahanadi, Penneiyar, Penneru, and Vaigai all flow eastward across the subcontinent, eventually forming vast deltas before emptying into the sea. These rivers tend to have larger drainage basins, gentle gradients, and more meandering paths, forming some of the most fertile and populous river plains on Earth.

Importantly, although they cover roughly three-quarters of India’s river catchments, they drain over 90% of the total water discharge in the country.

⬅️ Arabian Sea Drainage (West-flowing Rivers)

The remaining 23% of India’s drainage flows westward into the Arabian Sea.

This includes rivers like the Narmada, Tapi (Tapti), Mahi, Sabarmati, and numerous fast-flowing rivers descending from the Western Ghats (Sahyadri range) such as the Sharavati, Periyar, and Mandovi. These rivers are typically shorter and swifter, with steeper gradients and narrower valleys.

The Narmada and Tapi are two of the few major rivers in India that flow westward, running almost parallel to each other across the central highlands before entering the Arabian Sea. The valleys of these rivers are rich in alluvial soil and dense teak forests, supporting both biodiversity and human settlement.

✨ Note: The volume of water discharged by the Arabian Sea drainage is disproportionately smaller compared to its area. Despite covering nearly a quarter of the land, it accounts for less than 10% of India’s total river water discharge.

Each of these basins tells a story—not just of water and land, but of people, history, and culture. They influence rainfall patterns, crop cycles, biodiversity, settlement patterns, and even state politics. Together, India’s river basins form a hydrological mosaic as complex and ancient as the subcontinent itself.

💧 Hydrology: Rhythms of Water in a Monsoon Nation

India’s hydrology is a tale of powerful extremes—from glacial trickles to monsoon torrents, from bone-dry riverbeds to catastrophic floods. At its heart lies the seasonal pulse of the Indian monsoon, a complex climate phenomenon that breathes life into most of the country’s rivers, especially those in the south and central plateau.

☀️ A Tale of Two Sources: Glaciers & Rain

India’s rivers have two main sources of water:

In the north, rivers like the Ganga, Yamuna, and Brahmaputra originate in Himalayan glaciers. These rivers are perennial, sustained throughout the year by both snowmelt and rain. Their flow volume rises dramatically from June to September as the monsoon drenches the plains and the melting glaciers contribute to the torrent.

In the south, rivers such as the Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery depend almost entirely on monsoonal rainfall. These rivers often run dry or shrink to sluggish trickles outside the rainy season, creating stark contrasts between wet and dry months.

🌧 The Monsoon Effect

India receives over 70% of its annual rainfall during the monsoon season. This concentrated deluge transforms rivers into roaring highways of water. In some places, rivers rise by 10 meters or more in just a few weeks, bursting banks, rejuvenating wetlands, and flooding fields. The same rivers that appear lazy in April can become flood monsters by July.

This hydrological cycle is both blessing and burden—essential for rice paddies, drinking water, and power generation, yet unpredictable and increasingly erratic in a warming world.

💦 Groundwater and Aquifer Recharge

Many Indian rivers are intimately linked with groundwater systems. In the dry season, especially in the Indo-Gangetic Plain, rivers are sustained by underground aquifers that feed into the surface flow. But overextraction for agriculture and urban use is depleting this invisible reserve, causing rivers like the Yamuna to dry up in stretches or flow with only wastewater near major cities.

Conversely, rivers also recharge aquifers, especially when they meander through sandy floodplains. This dual relationship means that river health is tightly bound to subsurface hydrology—a connection often ignored in water management.

🔁 Flow Regimes: The Pulse of a River

Every river has a unique flow regime—its seasonal rhythm of rise and fall. These patterns define everything from agricultural cycles to fish spawning and migration patterns of birds. In healthy rivers, this rhythm is predictable. But in dammed and regulated rivers, the natural pulse is altered, often to the detriment of riverine life.

Hydrological studies now emphasize the importance of maintaining “environmental flows”—a minimum quantity of water that must be allowed to flow, even in dammed rivers, to sustain ecosystems.

🧠 The Challenge of Management

India’s hydrology is under constant stress:

- Climate change is making monsoons more erratic.

- Dams and diversions alter natural flow paths.

- Urban sprawl replaces wetlands that once absorbed seasonal floods.

- Agricultural overuse drains both rivers and aquifers.

Effective river management in India is no longer just about irrigation or flood control—it’s about balancing ecology, economy, and tradition in an age of rising temperatures and falling water tables.

From the glaciers of Gangotri to the mangrove tides of the Sundarbans, India’s hydrology is a living, breathing system—complex, sacred, and increasingly fragile. To understand India’s rivers is to understand time, rainfall, tradition, and science—braided like tributaries in a mighty stream.

🌿 River Ecology: From Himalaya to Tropical Wetlands

India’s rivers are not just channels of water—they are living ecosystems, stretching from the frozen Himalayan snows to the mangrove-tangled deltas of the Bay of Bengal. Along their journeys, they pass through an astonishing array of ecological zones, each with its own rhythm, scent, and species.

A single drop of water in the Ganga, Brahmaputra, or Godavari may glide past alpine meadows, subtropical forests, floodplain farms, and brackish mangroves—all in the same river’s flow. These dynamic landscapes host life in dazzling forms, many of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

The rivers born in the Himalayas are more than snowmelt and sediment—they are cradles of cold-water biodiversity. Their upper reaches teem with snow trout, Himalayan mahseer, and a fragile web of invertebrates adapted to fast-flowing, oxygen-rich currents. These cold streams sustain alpine vegetation and act as vital corridors for migratory birds, such as the bar-headed goose, who soar over the mountains guided by ancient instinct.

🏔️ Himalayan Headwaters: Icy Origins of Life

The rivers born in the Himalayas are more than snowmelt and sediment—they are cradles of cold-water biodiversity. Their upper reaches teem with snow trout, Himalayan mahseer, and a fragile web of invertebrates adapted to fast-flowing, oxygen-rich currents. These cold streams sustain alpine vegetation and act as vital corridors for migratory birds, such as the bar-headed goose, who soar over the mountains guided by ancient instinct.

Here, the rivers cut through pine forests, rhododendron groves, and high meadows grazed by yaks and bharal (blue sheep). The icy purity of these waters is revered not just spiritually—but ecologically.

🌾 Middle Reaches: The Riverine Heartlands

As rivers descend into the plains of northern and central India, their waters slow and warm. These middle stretches are rich with silt, nutrients, and life. Vast floodplains support fertile agriculture—rice, wheat, sugarcane—and create mosaic habitats of oxbow lakes, swamps, and riparian forests.

Here live iconic species such as:

- The endangered Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica), a blind yet graceful swimmer that navigates with echolocation.

- Softshell and hard-shell turtles, thriving in the quiet eddies and sandbanks.

- Mugger crocodiles sunning themselves near muddy shores.

- Wading birds like painted storks, ibises, and black-necked storks, elegantly combing the shallows for prey.

These floodplains are not just ecological hotspots—they are also deeply human landscapes, dotted with ghats, temples, fishing villages, and sacred rituals.

🍃 Peninsular Plateaus: Ancient Rivers, Ancient Life

The rivers of the Indian plateau—like the Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery—flow through older geological formations, supporting a different, often drier ecology. These rivers run through deciduous forests, grassy plains, and rocky outcrops, forming seasonal wetlands that come alive during the monsoon.

Species such as the giant river prawn, catfish, and freshwater mussels thrive here, while the surrounding forests shelter Indian leopards, sloth bears, and wild boars, all of whom drink from the riverbanks.

Many stretches of these rivers are lined with sacred groves and ancient temple towns, where nature and devotion have coexisted for centuries.

🌴 Coastal Lowlands & Deltas: Life at the Edge of Land and Sea

As rivers approach the coast, their final chapters unfold in vast, fertile deltas and estuaries—mystical, muddy, and alive with motion.

- The Sundarbans Delta, where the Ganga and Brahmaputra merge, is the world’s largest mangrove forest, a tangled refuge of roots and mystery. It is the last stronghold of the elusive Royal Bengal tiger, who swims between islands in search of prey.

- Mangrove ecosystems act as nurseries for fish, crabs, and shrimp, while mudskippers dance between tide and trickle.

- The mix of salt and fresh water creates a unique brackish habitat for species such as the irrawaddy dolphin and horseshoe crab.

These deltas also protect inland areas from storm surges, playing a vital role in climate resilience—though they themselves are now threatened by rising seas and human encroachment.

🌱 Rivers as Ecological Corridors

Beyond individual habitats, India’s rivers function as biological highways, allowing species to move, migrate, breed, and adapt. Otters, turtles, and fish follow the currents; birds use rivers as navigation lines during migration; and trees spread their seeds downstream. In a country where wilderness is increasingly fragmented, rivers remain the last threads of ecological continuity.

Yet, this rich ecological mosaic is fraying. Dams block migration routes. Pollution suffocates aquatic life. Riverine forests are cleared for fields and roads. But where rivers still flow free, life blooms in abundance.

To protect India’s rivers is not just to save water—it is to preserve thousands of interwoven lifelines, from plankton to people, from the Himalaya to the sea.

🏞 River Features: Sculptors of the Indian Landscape

Rivers are not merely carriers of water—they are ancient sculptors, etching valleys, carving gorges, building deltas, and shaping the very identity of the Indian subcontinent. Across millennia, they’ve molded not only the earth beneath our feet but the civilizations that grew upon their banks. To follow a river’s path is to trace the chisel marks of deep time upon the land.

⛰️ From Rugged Heights: Gorges and Rapids of the North

In their infancy, Himalayan rivers like the Alaknanda, Bhagirathi, Teesta, and Subansiri slice through sheer rock walls with raw, glacial force. Their turbulent youth is marked by:

- Deep gorges, like those of the Brahmaputra in Arunachal Pradesh—among the world’s deepest.

- White-water rapids that challenge rafters and echo with ancient thunder.

- Terraced valleys, carved by seasonal floods and landslides, now cradling mountain farms.

These rivers are powerful agents of erosion and sediment transport, their every flood reworking the canvas of the Himalayas.

🌾 Plains of Plenty: Alluvial Marvels and Oxbow Dreams

As they descend from the mountains, the rivers stretch and slow, braiding and meandering across the Indo-Gangetic plains. Here, they become:

- Architects of fertility, depositing nutrient-rich silt each year that sustains millions of hectares of farmland.

- Creators of oxbow lakes, the curving remnants of old meanders—now tranquil havens for birds and fish.

- Sources of sacred sandbanks and islands, where festivals unfold and pilgrimages converge.

The Ganga, in particular, builds one of the largest and most fertile deltas on Earth, nurturing the rice paddies of Bengal and wetlands of Bangladesh.

🪨 Plateau Passages: Cascades, Ravines, and Rocky Beds

The peninsular rivers tell a story of age and resilience. Flowing over ancient rock formations, they often display features unique to the old, stable crust of the Deccan and Chotanagpur plateaus:

- Spectacular waterfalls, like Jog Falls on the Sharavati, Chitrakote Falls on the Indravati (the “Niagara of India”), and Hogenakkal Falls on the Kaveri, where rivers tumble off escarpments in roaring curtains of spray.

- Steep gorges, such as those carved by the Narmada and Tapi through resistant basalt and granite.

- Rocky beds and pools, where water flows crystal-clear over smoothed stone, dotted with boulders and shaded by sal forests.

These features are both geological wonders and cultural landmarks, often surrounded by temples and legends.

🏝 Deltaic Worlds and Coastal Beauty

Where the rivers reach the sea, their artistry becomes even more complex. Over centuries, sediment-laden flows have formed:

- Vast deltas, like those of the Ganga-Brahmaputra, Mahanadi, and Godavari, where rivers branch into distributaries and wetlands.

- Estuaries, where freshwater mingles with salt, nurturing mangroves, fisheries, and human settlements.

- Coastal lagoons, such as Chilika Lake in Odisha, a brackish wonderland formed by the Mahanadi system and home to flamingos and Irrawaddy dolphins.

These features protect coastlines from erosion, support rich biodiversity, and form some of India’s most delicate ecological balances.

📿 Rivers as Mythical Landscapes

Indian rivers do more than shape land—they shape belief. Mountains become abodes of gods, waterfalls gain healing powers, and islands are believed to host divine footprints. Rivers like the Ganga are said to descend from heaven, breaking the Earth’s crust with cosmic force.

These features—natural yet numinous—anchor both the physical and spiritual landscapes of India.

Wherever you look in India, from mist-veiled Himalayan cliffs to sunlit coastal plains, rivers have sculpted beauty, bounty, and belief into the land. They are geologists, gardeners, and poets all in one—constantly reshaping a subcontinent that never stops flowing.

👥 People Along the Riverbanks

To walk along the banks of an Indian river is to step into the living heart of human civilization. Here, water doesn’t merely sustain life—it defines it. For millennia, people have built their homes, dreams, and rituals beside rivers. They’ve bathed their children, burned their dead, grown their crops, and sung their prayers to the same flowing waters. In India, a river is not just a natural feature—it is a neighbor, a deity, a witness, and a mirror.

🕉 Rivers as Sacred Beings

Few cultures personify rivers with such depth and devotion as India does. The Ganga is Ganga Ma, a goddess flowing from the locks of Lord Shiva himself. A bath in her waters is believed to purify karma and grant salvation. The Yamuna, too, is revered as the companion of Krishna, while the Saraswati—though vanished—is invoked in Vedic hymns.

Rivers are honored in rituals both grand and intimate:

- The Kumbh Mela, held at river confluences like Prayagraj, is the largest religious gathering in the world, where millions come to cleanse their sins.

- Chhath Puja, celebrated on riverbanks across northern India, venerates the setting and rising sun reflected in the water.

- Even daily life is filled with quiet acts of reverence: a whispered prayer, a floating lamp, a garland sent downstream with love.

🌾 Rivers as Providers

Beyond the spiritual, rivers are the economic lifelines of India. Over 70% of India’s agriculture depends on river irrigation, especially in the fertile Indo-Gangetic plains. Rivers feed:

- Rice paddies in Bengal and Odisha

- Sugarcane fields in Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra

- Cotton plantations in the Krishna and Godavari basins

- Vegetable-rich floodplains along the Yamuna and Kaveri

Rivers also support inland fisheries, vital for local livelihoods. Towns like Allahabad, Patna, Guwahati, Rajahmundry, and Tiruchirappalli have evolved alongside rivers—not just for sustenance, but as hubs of commerce, education, and art.

🛶 Rivers as Routes and Markets

Before railways and roads, rivers were India’s original highways. Boats ferried people and goods through the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and even smaller waterways like the Periyar and Mandovi. In Assam, long wooden boats still glide past rice fields and river islands. In Kerala, the famed backwaters remain both picturesque and practical.

Today, India is reinvesting in inland water transport, hoping to revive riverine trade in an eco-friendlier way.

🧺 Rivers and Everyday Ritual

In India’s villages and temple towns, the riverbank is the first and last stop of the day:

- Women gather at dawn to wash clothes, fill earthen pots, and exchange stories.

- Children swim in afternoon light, using banana stems as makeshift rafts.

- At dusk, diyas (oil lamps) are lit and set afloat—prayers carried gently downstream.

Even in cities like Delhi or Varanasi, where concrete crowds the river’s edge, the water remains a thread of continuity, a stage where life’s drama unfolds: birth, love, prayer, and farewell.

Yet, these human-river relationships are under strain. As cities swell and industrial demands grow, rivers once revered are now polluted, dammed, and degraded. Still, the cultural bond remains strong—sometimes stronger than the river itself. And in that bond lies both hope and responsibility.

In India, to live by a river is to be part of a sacred story—one that stretches across epochs and empires, across villages and rituals, and still flows forward, carrying people and memories alike.

⚠️ River of India: Threats and Conservation Challenges

India’s rivers—once wild, worshipped, and life-giving—are now among the most threatened in the world. What flowed as sacred and cyclical has become, in many places, choked, poisoned, and fragmented. Yet, even in their decline, rivers endure. Their pulse weakens, but it still beats—carrying with it the possibility of renewal.

🧪 Pollution: When Holy Turns Hazardous

In cities and towns, rivers often bear the brunt of unchecked urban expansion:

- Untreated sewage, industrial effluents, plastic waste, and chemical runoffs flow freely into rivers like the Yamuna, Ganga, and Musis.

- Sacred rituals, though spiritual, contribute further: immersion of idols, ashes, and offerings—rich in organic and non-biodegradable material.

- Agricultural runoff laced with pesticides and fertilizers adds to the toxic brew, triggering eutrophication and dead zones.

Once a habitat for dolphins and fish, many river stretches are now oxygen-deprived and biologically barren.

Indian rivers are among the most polluted in the world.

🚧 Dams, Diversions, and Fragmented Flow

India is home to over 5,000 large dams—concrete giants that generate hydroelectric power, store water, and tame floods. But their cost is ecological:

- Dams interrupt natural flow regimes, affecting sediment transport, fish migration, and seasonal flood cycles essential for soil renewal.

- Rivers like the Narmada have seen entire tribal communities displaced by large dam projects such as the Sardar Sarovar.

- Many Himalayan rivers, once free-flowing, are now strung with run-of-the-river projects that sap energy from even their uppermost reaches.

In trying to master the river, we have silenced its voice—its seasonal rise and fall, its floods and flushes, its very rhythm.

⛏ Sand Mining and Riverbed Exploitation

The hunger for urban growth has led to illegal and unsustainable sand mining from riverbeds, particularly in the Yamuna, Ganga, and Ghaggar. This not only destabilizes banks and deepens channels unnaturally but also destroys habitats for turtles, birds, and benthic organisms.

In places, rivers have become quarries rather than ecosystems.

🏙 Encroachment and Wetland Loss

As cities expand and floodplains are paved, rivers lose their natural buffers:

- Floodplains—which once absorbed excess monsoon water—are now parking lots, malls, and housing colonies.

- Wetlands that filtered pollutants and hosted migratory birds have vanished.

- Sacred tanks and ancient ghats are neglected or privatized.

When floodwaters come, they no longer seep away gently—they surge and destroy.

🔥 Climate Change: The Rising Threat

Climate change acts as a force multiplier, compounding existing threats:

- Glaciers in the Himalayas, the source of major northern rivers, are melting faster than ever. Their retreat could cause devastating floods now—and reduced flow in the future.

- Monsoons have become increasingly erratic, leading to both flash floods and prolonged droughts.

- Rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns threaten river-dependent agriculture, especially in eastern and southern India.

Climate change is rewriting the script of India’s hydrology—and we are still scrambling to read it.

🌱 The Flicker of Hope: Conservation Efforts

Amid the despair, glimmers of restoration and resistance shine through:

- Government initiatives like Namami Gange aim to rejuvenate the Ganga with better sewage treatment, industrial regulation, and riverfront beautification.

- Community-led cleanups, such as those along the Kumudvathi River in Karnataka or the Revive Bharalu project in Assam, are proving that local action can reverse degradation.

- Rewilding efforts, like reintroducing turtles or monitoring river dolphins, are rekindling biodiversity.

- Legal recognition of rivers as living entities, as in the case of the Ganga and Yamuna (though later overturned), sparks a new way of thinking: not managing rivers, but listening to them.

India’s rivers are at a threshold. One path leads to desiccation, conflict, and cultural amnesia. The other, though steeper, winds toward revival, resilience, and reconnection.

And in the pause between these two flows, we stand—not just as beneficiaries, but as guardians.

🌊 Conclusion

To understand India, one must understand its rivers. They are not merely features of the landscape—they are the landscape, flowing through its language, its music, its rituals, and its memory. From the whispering glaciers of the Himalayas to the silt-laden shores of the Sundarbans, rivers in India are living archives, recording the rise of cities, the fall of kingdoms, and the eternal rhythm of life itself.

They have fed empires and inspired epics, cradled biodiversity and ignited revolutions. And yet today, these same rivers strain under the weight of a billion needs—dammed, dredged, polluted, forgotten.

But rivers are resilient. They remember how to heal, if given the chance. With respect, action, and ancient wisdom, the flow can be restored. Because to save a river in India is to save not just water—but culture, climate, and collective future.

So let us walk once more to the riverbank.

Not just to take from the river—but to listen, to protect, and to give back.