Mythical Rivers: Legends of Styx, Lethe & River Gods

Explore mythical rivers from ancient legends—Styx and Lethe of the underworld, Amazon warrior tales, and crocodile gods of sacred waters.

Since the dawn of human imagination and civilizations, rivers have been more than just winding paths of water—they’ve been thresholds between life and death, wisdom and forgetting, power and mystery. In every corner of the world, people have looked to rivers and seen gods, ghosts, and warriors gazing back from the mythical rivers.

In this journey through mythical rivers, we’ll drift along the chilling currents of Styx, where souls cross into the underworld; sip the waters of Lethe, the river of forgetfulness; dive into the fierce legends of Amazon warrior women who ruled the jungle’s edge; and bask beneath the sunlit ripples of Nile-like streams ruled by crocodile gods.

These are not just rivers. They are sacred veins of ancient belief, pulsing with divine danger and immortal myth.

Styx: The River of Oaths and the Dead (Greek Mythology)

In the shadowed landscape of Greek mythology, few rivers carry as much weight and terror as the Styx. This was not a gentle, meandering stream but a solemn boundary between the living and the dead—a river whose waters no god dared to cross lightly. Flowing through the deepest realms of Hades, the Styx marked the edge of the mortal world and the entrance into the underworld. It was said that the dead could only pass if they were properly buried and honored; otherwise, they were doomed to wander eternally on the shores, unable to pay their passage.

Enter Charon, the skeletal ferryman cloaked in gloom, who guided souls across the Styx in his creaking boat. But he did not ferry just anyone. Payment was required—usually a coin, often an obol, placed under the tongue or on the eyes of the dead. Without it, the journey stalled, and the soul was left stranded in limbo. This rite of passage highlights not only the belief in a structured afterlife but also the deep fear of being forgotten or dishonored in death.

Yet the Styx was more than a river of the dead. Its waters held an unbreakable power: oaths sworn upon it were sacred, even to the Olympian gods. To break such an oath was to invite a fate worse than death—a year without breath, followed by nine more in exile. Even Zeus, the king of gods, respected and feared the Styx. It was to her that the gods turned when binding their most solemn promises. The goddess Styx herself, a daughter of Oceanus, was honored above many for lending her name to this binding force.

Symbolically, the Styx represents more than the boundary between life and death. It speaks of irrevocable choices and sacred loyalty. To cross it was to surrender the self entirely—no turning back, no second chances. It is the mythic embodiment of transition, of loyalty paid with silence, and of the high cost of betrayal. In many ways, the Styx is not just a river in myth but a mirror for the ultimate human truths: that some passages are final, some words irreversible, and some promises too holy to break.

Lethe: The River of Forgetting and Rebirth

In the hushed, dreamlike realm of the Greek underworld, among rivers of flame and sorrow, flowed one stream unlike the others: Lethe, the river of forgetting. To drink from Lethe was to surrender memory itself—to let go of every love, wound, promise, and name ever known. Its waters ran cool and silent, offering not terror, but a strange, almost seductive calm. Lethe did not punish; she washed away. And in that act, she became one of the most haunting symbols of rebirth in Greek mythology.

In the Orphic and later Platonic traditions, Lethe served a crucial role in the cycle of reincarnation. Souls returning to the world of the living were required to drink from the river so that they would forget their past lives. Only through amnesia could they be reborn into new flesh, carrying no trace of the sorrows, sins, or triumphs that had come before. In this view, forgetting wasn’t a loss—it was a mercy. A clean slate. A chance to begin again unburdened.

And yet, Lethe has always hovered in a space of contradiction. Is forgetting truly a gift? Or is it a quiet tragedy? To forget pain may be healing—but to forget love, truth, or identity is to lose oneself entirely. Greek thinkers wrestled with this tension. In later mystery religions, some initiates were told instead to drink from Mnemosyne, the pool of memory, rather than Lethe, in order to retain their soul’s wisdom through lifetimes.

This inner war—between forgetting and remembering, peace and pain—still echoes in modern art, literature, and psychology. Writers from Dante to Borges have invoked Lethe as a metaphor for oblivion or a healing forgetfulness. In psychological terms, she appears in discussions of repression and trauma, where memory itself becomes both the cause of suffering and the key to healing. In dystopian fiction, where societies rewrite or erase the past, Lethe flows metaphorically beneath the surface.

In all these guises, Lethe remains elusive. She asks the eternal question: Would you drink to forget? And what would you lose, in exchange for peace?

Not a river of fire or punishment, but of soft erasure, Lethe is a reminder that sometimes the most dangerous powers come not with thunder, but with silence.

Ask ChatGPT

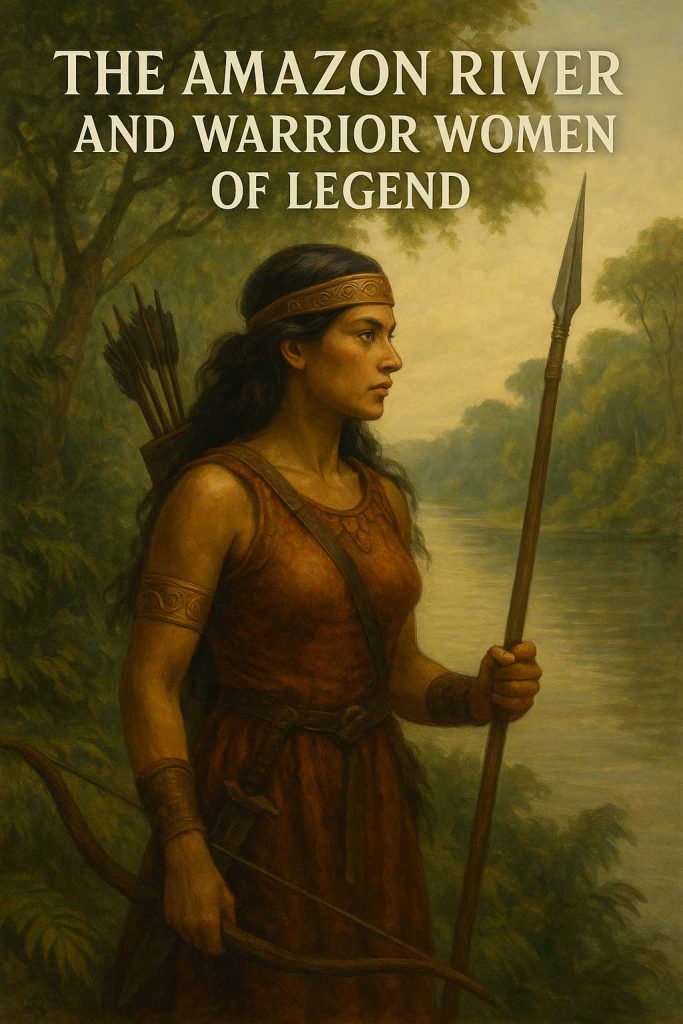

The Amazon River and Warrior Women of Legend

The Amazon River—mighty, serpentine, and shrouded in mist—has long been more than just a geographical marvel. It is a mythic artery, a symbol of wildness and feminine power, entwined with the legend of a fierce race of warrior women who, according to ancient Greek myth, lived far beyond the edges of the known world. These were the Amazons: archers on horseback, mothers without men, sisters of steel who governed themselves and refused submission.

Greek texts describe the Amazons as dwelling near the Thermodon River in Anatolia, but as geographical knowledge expanded, the name Amazon was later given to the South American river by early European explorers—most famously by Francisco de Orellana in the 16th century. His party, traveling down the river, reportedly encountered indigenous women warriors. Whether these accounts were exaggerated, romanticized, or confused interpretations of complex tribal societies, the legend stuck. The river was named Amazonas, and the myth of the jungle’s warrior queens took root in Western imagination.

But did the Amazons truly exist? For centuries, they were considered fantasy—figments of Greek imagination meant to symbolize chaos, femininity, or the “other.” Yet modern archaeology has reopened the question. Burial sites in the Eurasian steppes have revealed women interred with weapons, their skeletons bearing marks of horseback riding and combat wounds. These were likely Scythian or Sarmatian women—nomadic cultures known to the Greeks—lending weight to the idea that Amazon myths may have stemmed from real encounters.

Still, the Amazon River itself holds older truths. Long before European myths collided with its waters, the basin was alive with indigenous cosmologies, where rivers were not just lifelines but living beings—divine mothers, serpents, and storytellers. Among the Shipibo, Yawanawa, Asháninka, and many other peoples, the river is sacred. It sings, heals, punishes, and protects. Female deities like Yemanjá (in Afro-Brazilian syncretism) or Iara, the seductive river mermaid, reveal a deep reverence for water as both womb and force.

In this layered mythology, the Amazon River becomes a mirror of the feminine archetype—not docile, but commanding; not merely fertile, but dangerous and wise. It represents untamed nature, cyclical power, and spiritual ferocity, where the jungle itself defends its sovereignty like a warrior queen.

So whether in spear-bearing sisters or sacred river goddesses, the Amazon remains a realm where myth and truth blur like reflections on a restless current. It is a river of legends—but also, perhaps, a river born of legendary women.

Sacred Crocodile Rivers: Sobek and the Nile (Ancient Egypt)

Along the lush green banks of the Nile, where reeds whisper in the wind and the river’s current moves like time itself, crocodiles once ruled both water and worship. To ancient Egyptians, they were not merely beasts—they were divine incarnations, feared and revered as vessels of power. At the center of this awe stood Sobek, the crocodile-headed god, embodiment of the Nile’s primal force: strong, fertile, and untamable.

Sobek was no mild deity. He represented the chaotic strength of nature—the might of floodwaters, the aggression of predators, the fertility of fertile silt and growing crops. His visage was that of a crocodile, eyes gleaming above the waterline, both protector and devourer. He was invoked to ensure the Nile would rise, irrigate the fields, and sustain Egypt’s very existence. Without the river, there was no kingdom. Without Sobek, the river was blind.

But Sobek wasn’t only feared—he was honored with stunning devotion. Entire temples were raised in his name, the most famous being the Temple of Kom Ombo, where priests once kept live crocodiles in sacred pools, tended to with ritualistic care. When they died, they were mummified like pharaohs, wrapped in fine linens and buried in decorated tombs, their spirits guided to the afterlife as emissaries of the god himself. Archaeologists have unearthed entire necropolises of mummified crocodiles, a testament to how deeply the ancient Egyptians wove their environment into their spirituality.

The Nile itself was more than water—it was the divine spine of Egypt, a sacred artery flowing from the unknown south to the civilized north, from the realm of the gods to the lands of men. Every flood was a resurrection, every drought a warning. Its rising was not only measured in cubits but interpreted as the mood of the divine. And so, worship of Sobek and the river merged—rituals were performed on boats, prayers floated downstream, and offerings were tossed into its depths.

But Egypt was not alone in deifying crocodiles. Across sub-Saharan Africa, crocodiles appear as spirit guardians in river lore—symbols of strength, territorial wisdom, and sometimes even creation. In Southeast Asia, particularly in regions like Cambodia and Indonesia, ancient myths tell of crocodile ancestors and river gods who rule from beneath the currents. Even today, some tribes perform rituals to appease crocodile spirits before fishing or entering sacred waters.

In all these myths, the crocodile is not just a reptile—it is the river’s voice, teeth, and memory. And through Sobek, the Nile becomes more than geography. It becomes a divine threshold, guarded by jaws older than empires, and flowing with the power to nourish or destroy.

Sobek reminds us: what lives in the river is the river. And the river remembers.

Other Mythical Rivers Around the World

Beyond Styx and Lethe, the mythology of rivers flows through every culture like a secret lifeline, veining the world’s sacred texts and oral traditions. Some rivers still surge through their ancient channels; others have faded into mystery, their waters remembered only in song and scripture. Each one holds a different spiritual truth—wisdom, suffering, transformation, or judgment.

In India, the Sarasvati river once shimmered as the divine embodiment of wisdom, speech, and learning. Mentioned in the Rigveda as a mighty and sacred river, Sarasvati is said to have flowed parallel to the Ganges before vanishing into the sands of time—both literally and mythically. Though lost to geography, she endures as the goddess Sarasvati, whose name is invoked by scholars and artists alike. Her story blurs the line between geological disappearance and metaphysical transcendence: a river that once carried water, now carries knowledge.

The Maya envisioned death not as an end, but as a journey through the fearsome realm of Xibalba, the underworld. To reach it, one had to cross several rivers—of blood, scorpions, pus—each one a test of endurance and spiritual worth. These rivers were not simply physical hazards but moral mirrors, symbols of purification through suffering. In the Popol Vuh, the sacred text of the Kʼicheʼ Maya, heroic twins navigate these rivers as part of their mythic trials, revealing how deeply rivers were woven into the soul’s passage beyond life.

In Judeo-Christian tradition, the Jordan River becomes a symbol of spiritual renewal and divine covenant. It is where the Israelites crossed into the Promised Land, and where Jesus was baptized by John—transforming it into a sacred site of rebirth, cleansing, and new beginnings. To touch the waters of the Jordan was, and still is, to symbolically leave behind one’s old self and step into grace. Its mythic power lies not in danger, but in deliverance.

Farther east, the Huang He or Yellow River of China is often called the “cradle of civilization,” but also the River of Sorrow. Its floods, both life-giving and catastrophic, shaped not only the land but the Chinese imagination. Mythic emperors tamed its waters, poets mourned its wrath, and in folklore it became the boundary between worlds—where ancestors wait along the misty banks. The river’s golden sediment gave birth to dynasties, but it also swallowed entire cities. It is a myth not of gods, but of endurance.

Each of these rivers—Sarasvati, Xibalba’s trials, the Jordan, and the Huang He—tells its own myth of flow and transformation. Whether buried, crossed, or feared, these rivers remind us that water remembers, and wherever it flows, it writes stories that no fire can erase.

Conclusion: The Eternal Flow of Myth and Meaning

Rivers have always been more than water. They are the veins of myth, carrying the weight of memory, the echo of gods, the whispers of ancient people who sat by their banks and dreamed. From the infernal chill of Styx to the soft forgetfulness of Lethe, from the warrior pulse of the Amazon to the sacred roar of the Nile, each river we’ve explored is a portal—a way of understanding not only the world, but ourselves.

These mythical rivers still matter because they speak in symbols that haven’t aged. We still yearn for rebirth, still fear oblivion, still search for courage, for knowledge, for peace. In their flowing forms, rivers become metaphors for the transience of life, the power of choice, and the longing for something beyond. When a river divides the world of the living and the dead, it reflects our own uncertainty about what lies beyond the horizon. When its waters cleanse or forget, it asks us what we wish to release. And when it surges wild and full of spirit, it dares us to live more boldly.

In myth, rivers were gods and thresholds, mothers and monsters. In the real world, they remain sacred—vital to ecosystems, to history, to human settlement. But perhaps, even more profoundly, they remind us that stories flow like water: branching, deepening, nourishing everything they touch.

So the next time you stand by a river—whether it’s a quiet creek or a mighty torrent—imagine what myths it might carry. What gods sleep beneath the current? What truths drift just out of reach? These waters invite you to listen, to remember, and to wonder.

Because every river, in its own way, tells a story.

And every story, like every river, eventually leads us back to ourselves.