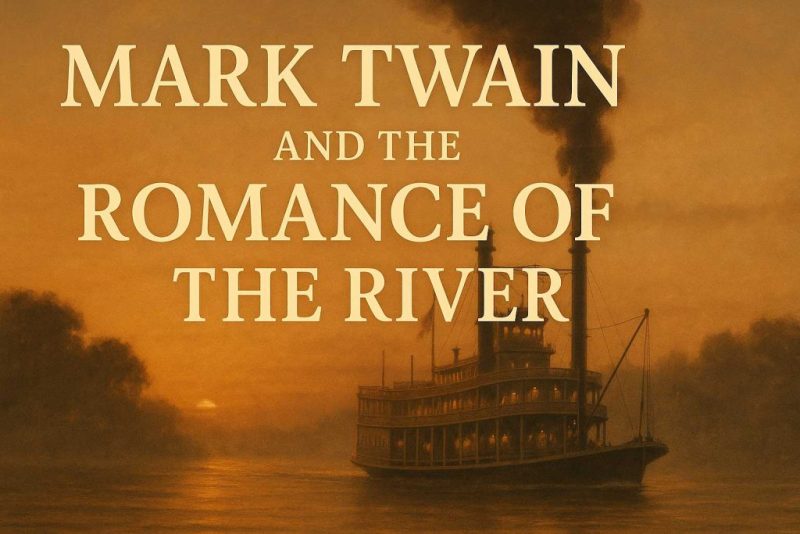

Mark Twain And The Romance Of The River-Steamboats, Stories, and the Soul of the Mississippi

Discover how Mark Twain immortalized the Mississippi River in American literature—where steamboats, satire, and sweeping currents shaped a nation’s myth and memory.

The Mississippi River doesn’t just flow through the heart of America—it pulses through its imagination. Few writers have captured its spirit like Mark Twain, whose pen transformed muddy waters into living legend. Born Samuel Langhorne Clemens in 1835, Twain didn’t just write about the river—he lived it, navigating its currents as a steamboat pilot before giving the world some of its most beloved characters and stories.

In Twain’s world, the river was not background—it was protagonist. A force of change, adventure, danger, and redemption.

Learn about other major rivers in the United States

The Steamboat Era: Romance on the Water

Before highways stitched their concrete threads across the land and railroads hammered steel veins into the heart of the continent, the river was everything. It carried not only goods and passengers but dreams, ambitions, and the slow swell of a young nation finding its shape. Along its wide, meandering arteries, the steamboat reigned supreme—a marvel of steam and spirit, gliding past cotton fields and frontier towns, its calliope echoing through the mist.

The steamboat era, stretching from the early 1800s to the outbreak of the Civil War, was a golden age of riverine romance and economic expansion. Paddlewheels sliced through the wilderness, their wakes trailing commerce, culture, and transformation. Decks glittered with chandeliers and fine gowns, even as below, the firemen and deckhands toiled in the heat of the boiler rooms. On these floating microcosms, society stratified and mingled in fascinating, often uneasy ways.

No one captured this layered world better than Mark Twain, the river pilot turned writer, whose Life on the Mississippi (1883) remains one of the most lyrical memoirs in American literature. His prose flows with the current—sometimes leisurely, sometimes sharp—blending autobiography, observation, and sly wit. He takes readers into the wheelhouse, where steering by instinct and starlight could mean the difference between safe passage and catastrophe. He reveals the silent codes between pilots, the dangers of invisible snags and ever-shifting sandbars, and the reverence held for the river’s moods.

For Twain, the Mississippi wasn’t just a backdrop—it was a character, unpredictable and proud, sometimes benevolent, sometimes deadly. A teacher of humility. A keeper of secrets. A vein of life running through the American story.

Huck and Jim: The River as Escape and Reckoning

Perhaps the most enduring of Mark Twain’s river tales unfolds in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), a novel often called the first great American novel. Here, the Mississippi River becomes more than a setting—it becomes the lifeline and moral compass of a journey that cuts to the heart of American identity.

Young Huck Finn, fleeing the suffocating grip of “civilization,” and Jim, an enslaved man escaping bondage, set off on a rickety raft, not knowing whether the river will lead them to safety or ruin. In those long, meandering drifts southward, the river becomes a paradox: a sanctuary that frees them from the injustices of society, and a crucible that confronts them with its deepest contradictions.

As they float along under star-strewn skies or hide among the willows during the day, the river offers a rare kind of space—liminal, fluid, unclaimed—where friendship can blossom, illusions can fall away, and the conscience can awaken. Huck wrestles with everything he’s been taught, especially when choosing between what’s “right” by law and what’s right by heart. His decision to help Jim, despite believing he’ll be damned for it, is one of the most powerful moral reckonings in American literature.

The Mississippi in this story is not a gentle guide—it’s vast, winding, unpredictable, at times treacherous. It mirrors the American soul: conflicted, capable of grace and cruelty in equal measure. Twain uses the river to explore themes of freedom and captivity, belonging and exile, illusion and truth—and in doing so, he casts the river as a timeless metaphor for the journey toward justice and self-discovery.

Their voyage is not just physical—it is spiritual, political, and deeply human. Through Huck and Jim, Twain shows us that the river, like the country it flows through, holds both peril and possibility.

Myth and Memory

Through the pen of Mark Twain, the Mississippi River transcended its physical boundaries and entered the realm of myth—not merely as a waterway but as a living thread woven through the American psyche. His river is not mapped by coordinates but by emotion, memory, and imagination. It is a place where time folds, where the innocence of boyhood meets the weight of moral choice, and where the muddy banks hold both laughter and loss.

In The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, the Mississippi becomes a stage for mischief and magic—a place where children play pirate, where rafts become kingdoms, and where the rules of the adult world blur into the currents. But beneath the playful surface, there’s always something deeper: the quiet pull of freedom, the ache of growing up, the confrontation with injustice. Twain imbues the river with a spirit that is both nostalgic and unsettling, as if it remembers everything and forgets nothing.

Even now, more than a century later, Twain’s vision shapes how we perceive rivers across the globe. They are not just sources of life or commerce—they are narrative backbones, flowing through history, memory, and myth. His Mississippi reflects the soul of a nation: restless, reflective, vast. It reminds us that rivers are not only carved by water and time but also by story and spirit—and in that sense, they never stop flowing.

The Eternal Current

Mark Twain’s Mississippi flows forever through literature, culture, and national identity. It reminds us that rivers are never just rivers—they are metaphors, muses, and mirrors. They carry us forward while always echoing the past.

And as long as there are rivers to follow, Twain’s voice will ripple through them, wry and romantic as ever.