Rivers in China: Lifelines of a Vast and Ancient Land

Discover the most iconic rivers in China—from the mighty Yangtze to the mystical Yellow River—shaping history, culture, and landscapes across the nation.

From the snowbound peaks of Tibet to the subtropical deltas of the South China Sea, the rivers of China carve through a landscape of dizzying diversity. These ancient waterways have long been the beating heart of Chinese civilization—cradles of dynasties, arteries of trade, and symbols of both power and peril.

Today, as China rapidly modernizes and expands, its rivers are once again at the center of transformation—no longer just historical lifelines, but engines of the nation’s development. Mega-projects like the Three Gorges Dam have turned rivers into monumental powerhouses, generating vast amounts of electricity and symbolizing human ambition on a grand scale.

But this progress comes at a price. Dams disrupt fragile ecosystems, displace communities, and transform the natural rhythm of rivers. The very lifelines that built China are now under threat, caught between the urgency of energy and the call of conservation.

In this journey, we’ll explore the most important rivers in China, from the legendary Yangtze and Yellow Rivers to lesser-known beauties like the Li River and Nujiang. These rivers not only shape the land—they nourish it, inspire poets, power cities, and connect people across thousands of kilometers.

Whether you’re dreaming of drifting through karst cliffs in Guilin or diving into the cultural lore of the Huang He, this guide will introduce you to China’s most captivating rivers—natural wonders where history, development, and ecology flow together. China’s most captivating rivers—natural wonders where history and nature flow together.

Discover More Iconic Rivers Across Asia

Rivers in China – Geography & Geology

The rivers of China are born in landscapes that defy uniformity—from glaciated peaks and tectonic folds to loess plateaus and subtropical plains. To understand how these rivers carve their paths and shape the land, we must begin with the geological and geographic context that underpins their existence.

Tectonic Origins: The Roof of the World

Many of China’s great rivers begin their journey on the Tibetan Plateau, a colossal uplift formed by the ongoing collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. This active geologic zone has birthed not just rivers but the very altitude and drama of China’s terrain—from the jagged Himalayas to deep-cut valleys like the Tiger Leaping Gorge.

It is here, amidst eternal snowfields and wind-scoured mountains, that rivers like the Yangtze, Yellow River (Huang He), and Mekong (Lancang Jiang) emerge—fed by glacial melt, highland springs, and rainfall.

From Highland to Heartland: The River Paths

As these rivers descend, they follow a classic topographical arc:

- Western China is mountainous, with steep gradients and narrow gorges.

- Central China unfolds in hilly basins and fertile plains.

- Eastern China flattens into coastal lowlands, where rivers fan out into complex deltas.

This west-to-east slope has allowed rivers to cut deeply into bedrock, deposit vast amounts of sediment, and sustain both ancient civilizations and modern megacities along their banks.

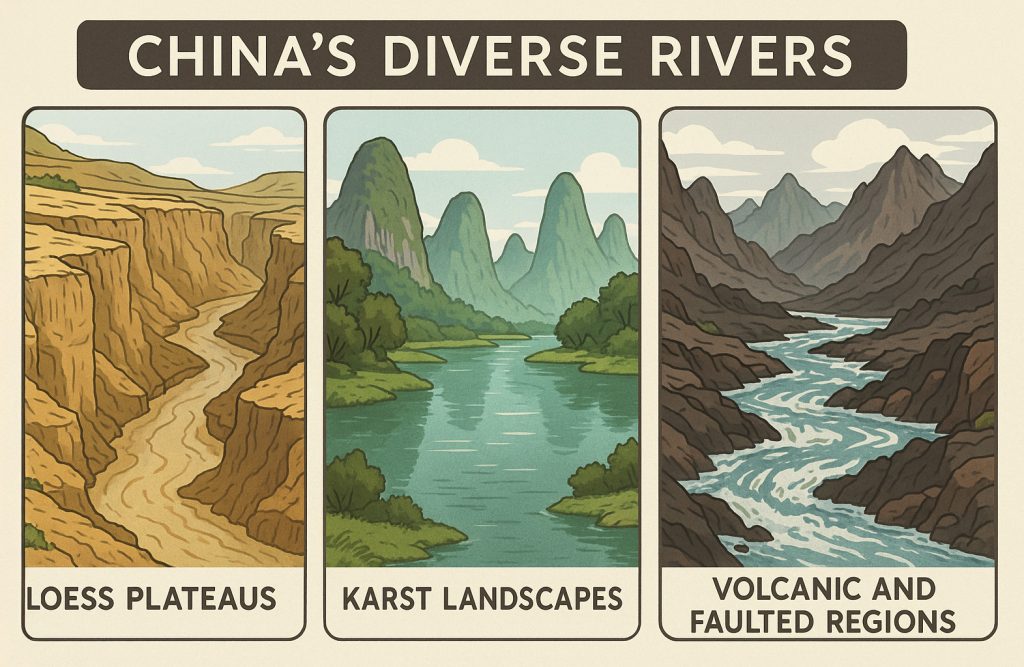

Geological Diversity Along the Way

China’s rivers don’t follow a single script. Their journeys traverse:

- Loess plateaus, where soft, wind-blown sediments are easily eroded—like in the Yellow River’s crumbling canyons.

- Karst landscapes, where rivers like the Li River glide past limestone towers, creating surreal scenery.

- Volcanic and faulted regions, where water has exploited cracks and fractures for millennia.

The bedrock beneath each river determines not only its path, but also the color of its waters, the fertility of its floodplains, and the risks of erosion or flooding.

Major Drainage Basins and Catchments

— Where the Waters Flow

China’s vast and uneven terrain is laced with one of the most complex and influential networks of rivers on Earth. These river systems do not flow randomly; instead, they follow ancient patterns dictated by the rise of mountains, the tilt of valleys, and the pull of gravity toward distant seas—or nowhere at all.

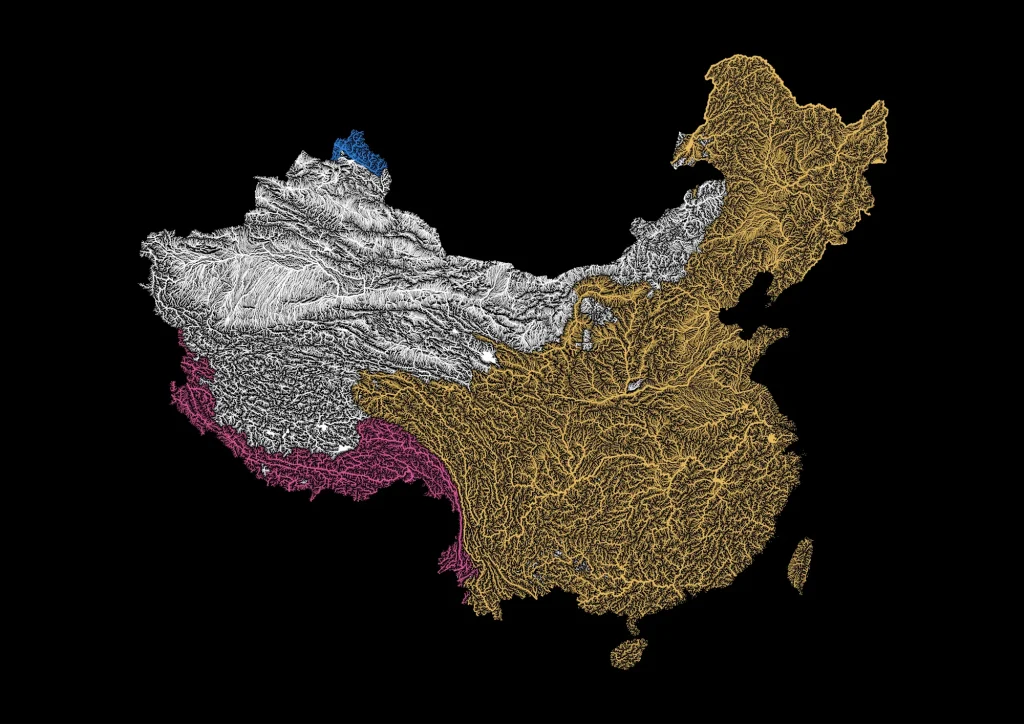

At the heart of this system are three major drainage basins that define how water moves across the Chinese landscape:

- The Pacific Ocean Basin

- The Indian Ocean Basin

- The Inland (Endorheic) Basin

Together, these catchment zones form the hydrological backbone of China, influencing everything from climate and agriculture to geopolitics and biodiversity.

1. The Pacific Ocean Drainage Basin: Arteries of the East

This is by far the largest and most economically significant basin in China. It captures the flow of many major rivers, including:

- The Yangtze River (Chang Jiang): Asia’s longest river and the lifeblood of central China, it drains a vast corridor of mountains, plains, and megacities before emptying into the East China Sea near Shanghai.

- The Yellow River (Huang He): Known as the cradle of Chinese civilization, it winds through the loess plateaus of the north, bringing both nourishment and devastation.

- The Pearl River (Zhujiang): Flowing through the lush subtropics of southern China, it nourishes the fertile delta that includes Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong.

These rivers form vast, multi-tiered catchment systems, with countless tributaries and sub-watersheds that sustain over a billion people, support rice fields and factories, and deliver silt and stories to the coast.

2. The Indian Ocean Drainage Basin: Rivers from the Snowlands

In the shadow of the Himalayas, rivers flow not east, but south and west, breaching the highlands and plunging into the Indian subcontinent. Chief among them:

- The Yarlung Tsangpo (Upper Brahmaputra): Born from the glacial heart of the Tibetan Plateau, this river takes a dramatic U-turn through the world’s deepest gorge—the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon—before exiting China and becoming the Brahmaputra in India and Bangladesh.

While smaller in terms of China’s total area, this basin is crucial for regional water security and harbors some of China’s wildest, most inaccessible watersheds, including glacial lakes and high-altitude wetlands.

3. The Inland (Endorheic) Basins: Rivers to Nowhere

In the arid northwest, the land tilts inward. Here, rivers are trapped by mountains and desert basins, unable to reach the sea. These are endorheic basins, where water ends in evaporation or salt lakes, not in oceans.

Key rivers include:

- The Tarim River: Flowing through the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, it is China’s longest inland river, feeding dying lakes like Lop Nur and supporting oasis towns along its margins.

- The Heihe and Shiyang Rivers: These smaller, seasonal streams sustain fragile ecosystems and ancient Silk Road settlements on the edge of the Gobi Desert.

These catchments are precarious and intensely vulnerable to climate change and overuse. With no outlet to flush them clean, they accumulate pollutants and salts, turning once-lush basins into dustbowls.

All Roads Lead from the Plateau: The Tibetan Watershed

What unites these three drainage basins is a single source: the Tibetan Plateau, often called the “Water Tower of Asia.”

- With an average elevation of 4,500 meters and dozens of glaciers, this massive upland holds the headwaters for all of China’s major rivers and many of Asia’s greatest systems, including the Mekong, Salween, and Irrawaddy.

Snowmelt, glacial ice, monsoon rains, and ancient tectonic uplift come together in this region to give birth to rivers that shape entire civilizations—not only in China, but across half the Asian continent.

Rivers in China – Hydrology

Pulse and Power in China’s Great Rivers

If geography gives China’s rivers their shape, then hydrology gives them life—the movement, volume, and rhythm of water as it journeys across the land. In China, that rhythm is anything but uniform. The country’s rivers span astonishing hydrological extremes, shaped by vast differences in climate, elevation, seasonal rainfall, and human engineering.

Monsoons and Meltwaters: The Dual Engines of Flow

In the south and southwest, China’s rivers are fed by the fierce, life-giving forces of the Asian monsoon. From late spring through summer, rainstorms swell rivers like the Pearl and Mekong (Lancang Jiang), causing water levels to rise dramatically—sometimes dangerously—before retreating into calmer, drier flows in winter.

In the west, especially in the Tibetan Plateau, rivers are driven by glacial and snowmelt. These meltwaters feed great arteries like the Yangtze and Yarlung Tsangpo, pulsing downstream with seasonal consistency but growing increasingly erratic as climate change warms the highlands.

In contrast, northern China is drier and more seasonal. Rivers like the Yellow River (Huang He) are snow-fed and rain-starved, with irregular, sometimes violent surges followed by long periods of low flow.

A Changing Pulse: Climate and Uncertainty

All of China’s rivers are now experiencing greater hydrological uncertainty.

- Monsoons are less predictable.

- Glaciers are shrinking.

- Floods are becoming more extreme.

- Droughts are more frequent.

This volatility has major implications for agriculture, drinking water, hydropower, and ecosystem health. Rural farmers watch the skies nervously. Engineers reprogram dam releases. Ecologists track collapsing fish populations and vanishing wetlands.

The natural rhythm of China’s rivers—once steady enough to build civilizations upon—is now under intense and unpredictable strain.

Major Rivers in China

The Yangtze River: A Colossus Under Control

At over 6,300 kilometers, the Yangtze River is not only the longest river in Asia, but also one of the most engineered. Its hydrology has been profoundly altered by dozens of massive dams, the most famous of which is the Three Gorges Dam—a superstructure that symbolizes China’s modern power but also its ecological gamble.

The dam controls floods, generates vast amounts of hydroelectric power, and enables shipping deep into China’s interior. But it also disrupts the river’s natural pulse, alters sediment flow, and has displaced millions. The Yangtze’s hydrology now dances to a human rhythm as much as a natural one.

The Yellow River: China’s Sorrow, China’s Soil

The Yellow River, Huanghe, is a hydrological paradox—shorter than the Yangtze, yet far more volatile. Its waters are choked with fine, yellow loess sediment from the northern plateaus, making it one of the siltiest rivers on Earth.

This sediment builds up in the riverbed, forcing the water to rise higher than the surrounding land in many stretches—a phenomenon that has led to catastrophic floods throughout history. Known as “China’s Sorrow,” the Yellow River has changed course dozens of times, claiming lives and reshaping entire provinces.

Modern levees and reservoirs have tamed it somewhat, but the river remains fragile. In dry years, it fails to reach the sea, and in wet years, its floods still test the limits of human control.

The Mekong (Lancang Jiang): Hydropolitics in Motion

Flowing from Tibet through China’s Yunnan province and onward into Southeast Asia, the Lancang Jiang (Upper Mekong) is a transboundary river with a highly sensitive hydrology.

Its seasonal surges—dictated by monsoon rains and snowmelt—once supported floodplain farming, fisheries, and rice cultivation downstream. Today, however, a cascade of upstream dams in China is transforming the river into a series of reservoirs, regulating its natural cycles in ways that are beneficial for Chinese energy needs, but often disruptive for countries downstream like Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

The Mekong’s flow is no longer simply a matter of rainfall—it’s a story of geopolitics, resource control, and shifting regional dynamics.

River Ecology: From High Mountains to Desert

River Ecology: From High Mountains to Desert

— Lifelines Through Changing Landscapes

As China’s rivers journey from their alpine birthplaces to distant deltas and deserts, they weave through an extraordinary array of ecosystems. Each bend in the river, each change in altitude or soil, marks a new biological zone—a chain of life zones linked by flowing water. These rivers are not just channels—they are living corridors that connect species, habitats, and human livelihoods across one of the most ecologically diverse countries on Earth.

Where the Snow Melts: Alpine Origins

High in the Tibetan Plateau, rivers begin their lives in glacial lakes, permafrost seeps, and alpine wetlands. These cold, clear waters support mosses, sedges, and migratory waterbirds, while surrounding slopes offer refuge to snow leopards, blue sheep, and hardy high-altitude herbs.

In the upper Yangtze (known as the Jinsha River), these cold mountain habitats are crucial for endemic amphibians, rare alpine plants, and the fragile beginning of the river’s sediment and nutrient journey.

Middle Reaches: Forests, Wetlands, and River Meadows

As rivers descend into temperate foothills and lowland valleys, they broaden, slow, and diversify. This is where biodiversity flourishes:

- The Yangtze River’s middle reaches flow through rich floodplains, lake complexes, and reed beds. These are home to the Yangtze finless porpoise, an endangered freshwater dolphin known for its expressive face and gentle demeanor.

- Wetlands along this stretch also support cranes, storks, and hundreds of fish species, some found nowhere else on Earth.

- The Yellow River, though heavily impacted by human activity, still nourishes seasonal wetlands and agricultural zones that feed both people and wildlife.

These middle zones act as ecological hearts, where rivers are richest in productivity and life.

Lower Reaches: Deltas and Estuarie

Near the coast, rivers slow to a crawl, branching into labyrinthine deltas and estuarine wetlands. Here, freshwater meets the sea, and brackish ecosystems emerge—nurseries for fish, havens for migrating birds, and crucial buffers against flooding.

The Yangtze Delta and Pearl River Delta are especially significant, not only for biodiversity but for their role in feeding hundreds of millions of people, producing rice, fish, and freshwater crabs while also hosting some of the most urbanized landscapes in the world.

Despite this human presence, these zones remain globally important stopovers for birds like the spoon-billed sandpiper and the black-faced spoonbill.

Northwest China: Desert Oases and Fragile Arteries

In stark contrast, rivers like the Tarim, Heihe, and Shiyang flow into the deserts of Xinjiang and Gansu. These waters thread through some of the driest regions in Asia, sustaining poplar forests, Bactrian camels, wild donkeys, and endemic fish species adapted to extreme salinity and fluctuating flows.

Here, the river is a thin green line, a lifeline in a sea of sand. Even small diversions upstream can lead to the collapse of entire oases downstream, making these systems ecologically and politically fragile.

River Features: Sculptors of the Chinese Landscape

— Where Water Carves, Life Follows

Rivers are more than flowing water. They are artisans of the land—chiseling rock, painting valleys, and shaping the contours of a nation. Over millions of years, China’s rivers have sculpted some of its most iconic and awe-inspiring landscapes. From towering canyons and thundering waterfalls to fertile valleys steeped in legend, these natural features are both the work of erosion and the canvas of culture.

Canyons: Where Rivers Cut Deep

China’s canyons are not just dramatic—they are monumental. Formed by relentless water carving through resistant stone, they reveal the bones of the Earth and offer refuge for rare species and ancient traditions.

- Tiger Leaping Gorge, one of the deepest river canyons in the world, lies where the Jinsha River (upper Yangtze) crashes through the Hengduan Mountains. With cliffs that rise over 3,000 meters from river to peak, it’s a place of myth, mist, and raw power.

- The Three Gorges—Qutang, Wu, and Xiling—were carved by the Yangtze River through limestone and sandstone ridges, creating a corridor of towering cliffs and ancient rock carvings, now partially submerged behind the Three Gorges Dam.

- In the Loess Plateau, the Yellow River has carved steep-sided, collapsing gorges through soft, wind-deposited silt—unstable, ever-changing canyons that tell a different, dustier story.

These canyons aren’t just scenery—they are cultural arteries, trade routes, battlegrounds, and spiritual sanctuaries.

Waterfalls: Rivers in Freefall

China’s waterfalls are liquid exclamations, moments where rivers momentarily abandon their steady descent and leap with wild abandon.

- Huangguoshu Waterfall in Guizhou, at 77.8 meters high and 101 meters wide, is one of Asia’s largest and most visited waterfalls. It crashes into a verdant limestone basin surrounded by caves and legends.

- Nuorilang Waterfall in Jiuzhaigou National Park spills down moss-covered cliffs into turquoise pools, a living postcard of color and sound.

- In the Yunnan highlands, rivers like the Nujiang form steep cascades as they descend from glacial origins to tropical forests.

Each waterfall represents a geological quirk: a resistant rock layer, a sudden drop, or a tectonic uplift—and each gives birth to microclimates, mists, and sacred sites.

Valleys: Where Civilizations Root

If canyons are dramatic and waterfalls thrilling, valleys are quietly transformative. Rivers don’t just dig—they nourish, turning barren corridors into green tapestries where people and ecosystems thrive.

- The Yangtze River Valley is China’s agricultural backbone, producing rice, tea, and silk for millennia. It is wide, humid, and fertile—a cradle of emperors and engineers.

- The Yellow River Valley holds the ruins of early Chinese dynasties and ancient irrigation systems. It’s a harsher, dustier environment, but one soaked in historical gravitas.

- Smaller valleys, like those of the Li River, are sculpted between karst towers, offering a dreamlike fusion of water and stone that has inspired poets and painters for centuries.

Valleys provide shelter, soil, and sustenance, making them the most human of river features—the places where water meets story.

Rivers as Geologists, Artists, and Storytellers

Together, these features—canyons, waterfalls, and valleys—tell a deeper tale. Rivers are not passive elements of geography. They are active creators, continually reshaping landforms and leaving behind layers of history, beauty, and complexity.

In every bend of a river-cut gorge, in every thunderous fall of water, in every quiet valley where willows bend toward the current, you see the hand of time—and the poetry of flow.

People Along the Riverbanks

People Along the Riverbanks

— Where Water Nourishes Civilizations

China’s rivers are not just natural features—they are lifelines of culture, memory, and survival. For over 5,000 years, people have followed, farmed, fished, worshipped, and fought along their shifting banks. Where the water flows, life flourishes. The rhythms of the river are reflected in Chinese poetry, painting, politics, and even cuisine.

The Yellow River: Cradle of Civilization

Often called the “Mother River of China,” the Yellow River basin gave birth to the earliest dynasties—the Xia, Shang, and Zhou. Along its loess-rich floodplains, humans first tamed the wild river to irrigate millet and wheat, build cities, and forge an identity. But it has always been a river of extremes.

The same waters that nourished the Han heartland also brought catastrophic floods, famine, and forced migrations. Today, the Yellow River still feeds northern farms and industrial towns, but its role has shifted—from cradle to cautionary tale, as climate change and overuse threaten its very flow.

The Yangtze: Powerhouse of the Present

Further south, the Yangtze River pulses through one of the most dynamic regions on Earth. From misty gorges in Sichuan to the skyscrapers of Shanghai, it connects ancient water towns like Wuzhen and Zhouzhuang with global finance and megacities of steel and glass.

In the Yangtze Delta, China’s economic engine churns—shipping ports, rice paddies, manufacturing zones, and high-speed rail. Yet just upstream, locals still harvest lotus root, paddle narrow boats, and offer incense to river gods. It’s a landscape where dynasties and data centers coexist, all bound together by water.

Minority Cultures: Guardians of River Traditions

In China’s southwestern provinces—Yunnan, Guangxi, and Guizhou—a rich mosaic of ethnic minority cultures lives intimately with the rivers.

- The Dai people celebrate the Water Splashing Festival every April, joyously drenching one another to bless the year ahead, a symbolic act rooted in river reverence.

- The Bai build their towns around lakes and canals, practicing centuries-old fishing and cormorant traditions.

- The Naxi, in the upper Yangtze valley, maintain unique script, music, and river rituals, shaped by the flow between Himalayas and lowlands.

These communities offer a glimpse into a more ancestral relationship with water—one of balance, respect, and seasonal awareness.

From Fisherfolk to Floating Cities

China’s riverbanks are not frozen in time—they are constantly evolving. Fisherfolk cast their nets at dawn, rice farmers tend terraced paddies, boat traders ferry goods, and urbanites jog along riverside promenades in megacities like Wuhan, Nanjing, and Guangzhou.

Floating markets, river ferries, stilt houses, hydroelectric plants—each tells a different chapter of China’s river story. And in every region, rivers shape the dialects spoken, the food eaten, the festivals celebrated, and the future imagined.

In China, to live by the river is not merely a matter of geography—it’s a way of life, a source of identity, and a continuous dialogue between the past and the future, between nature and civilization.

Economic Significance of China’s Rivers

— Waterways of Power, Production, and Progress

While rivers have always been cradles of civilization, in modern China they have become engines of economic growth. In no other country do rivers play such an integral role in fueling both tradition and transformation. Today, they power cities, feed industries, carry goods, and irrigate the fields that feed the nation. China’s rise as a global powerhouse has flowed—quite literally—along its rivers.

Hydropower: Dams as Symbols of Ambition

China leads the world in hydropower production, and its rivers are the bedrock of this energy boom.

- The Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze is the largest hydroelectric facility on Earth, generating over 100 terawatt-hours of electricity annually—enough to power entire provinces.

- Across the country, tens of thousands of dams—large and small—generate renewable energy, control floods, and regulate water for agriculture.

But this energy revolution comes at a cost: ecosystem disruption, sediment trapping, displaced communities, and increasing tension in downstream nations who rely on the same waters.

River Navigation: Inland Arteries of Trade

Rivers are not only sources of power but natural highways for inland transport.

- The Yangtze River is navigable for over 2,000 kilometers, connecting Chongqing in the interior to Shanghai on the coast.

- Barges carry everything from coal and steel to grain and electronics, dramatically reducing freight costs and emissions.

The government has heavily invested in port modernization and dredging, making river shipping a key player in China’s logistics and supply chain strategy.

Even smaller rivers support local economies—moving goods, hosting floating markets, or providing scenic routes for river tourism and heritage cruises.

Irrigation and Agriculture: Feeding a Nation

China’s great rivers have transformed arid and seasonal landscapes into agricultural heartlands.

- The Yangtze Delta produces rice, freshwater fish, lotus root, and vegetables, helping supply over 400 million people.

- The Yellow River, though less reliable today, remains vital to the wheat-growing regions of the north.

Vast networks of canals, pumps, and diversions bring river water to thirsty plains and highland terraces. In dry provinces, every drop is accounted for, managed through strict quotas and irrigation schedules.

Industrial and Urban Development

Where rivers flow, cities and factories grow. Water is essential for:

- Cooling power plants

- Processing textiles, steel, and electronics

- Supporting urban populations with drinking water, sanitation, and transport

Industrial clusters have risen along the Yangtze, Pearl, and Min Rivers, transforming once-quiet towns into manufacturing hubs and export giants. Yet this rapid growth often brings pollution, resource competition, and rising pressure on water infrastructure.

China’s rivers are not just natural features—they are economic lifelines, shaping everything from electricity grids and rice fields to shipping routes and smart cities. Their flow carries not only water, but the weight of a nation’s ambition.

Threats and Conservation Challenges

— Can the Lifeblood of China Endure?

China’s rivers, once flowing wild and free, are now under immense strain. As engines of economic growth and civilization, they’ve borne the weight of transformation—but at a cost. Pollution, damming, climate instability, and biodiversity loss are pushing many river systems to the brink. What was once natural rhythm is now interrupted flow; what was once ecological richness is now a fight for survival.

Pollution: Rivers Strangled by Progress

In northern and industrial regions, rivers like the Hai, Yellow, and Huai have become repositories for chemical runoff, heavy metals, fertilizers, and untreated sewage.

- Agricultural intensification has led to nutrient overload, fueling algae blooms and oxygen depletion.

- Industrial zones dump toxic waste and microplastics into river channels once teeming with life.

While monitoring and regulation have improved in recent years, many tributaries remain biologically dead or dangerous to touch, particularly in urban and peri-urban corridors.

Dams and Diversions: Fragmenting the Flow

China’s grand infrastructure projects—dams, reservoirs, water transfer canals—have brought electricity and water security to millions. But they’ve also:

- Trapped sediment, starving deltas and floodplains of renewal.

- Interrupted fish migrations, cutting off life cycles mid-stream.

- Displaced entire communities, often without proper compensation.

The Three Gorges Dam, while a marvel of engineering, has flooded ancient towns, triggered landslides, and created complex ecological ripple effects downstream. Smaller rivers face “hydraulic strangulation”—dammed every few kilometers, their flow segmented and silenced. Learn more about the downsides of river damming

Climate Change: Unpredictable Waters

The once-reliable seasonal rhythms of rivers are now increasingly erratic.

- Southern China faces more intense flooding, especially during typhoon season.

- Northern China struggles with persistent drought, shrinking lakes, and failing aquifers.

- Glacial retreat in the Tibetan Plateau threatens to reduce long-term river flow across all of Asia.

Extreme weather events—once rare—are now common, making both flood management and agricultural planning more precarious than ever.

Biodiversity in Crisis

China’s rivers once hosted some of the most unique freshwater species on Earth, but many are now extinct or critically endangered.

- The Chinese paddlefish, a prehistoric giant of the Yangtze, was declared extinct in 2020.

- The Yangtze sturgeon and finless porpoise teeter on the edge, hemmed in by pollution and dams.

- Wetland birds, amphibians, and native fish are disappearing from rivers where they once thrived.

Every species lost is more than a number—it’s a thread cut from a living tapestry.

Hope on the Horizon

Despite these challenges, China has begun to turn the tide:

- New national parks, including those in the Yangtze River basin, are protecting crucial habitats and buffer zones.

- Wetland restoration projects are reviving biodiversity and improving water quality.

- Public awareness campaigns and citizen-led river cleanups are growing, especially among younger generations.

- Ecologists and engineers are collaborating on “ecological flow” models to restore river rhythms without halting development.

There is now recognition that rivers are not just water—they are living systems, and protecting them is protecting China’s future.

The rivers of China have sculpted landscapes, nourished empires, and inspired poets. Now, in the 21st century, the question remains: can they continue to sustain life amid pressure, pollution, and progress?

The answer lies in whether conservation can match ambition—and whether humanity can rediscover its place within the flow, not just above it.

Conclusion

China’s rivers are more than lines on a map—they are living legacies of geology, culture, and resilience. As they rush toward the sea or disappear into desert, they carry the memory of emperors, farmers, poets, and engineers. To understand China, you must understand its rivers—for in their flow lies the pulse of a nation, ancient and alive.