Rivers of Asia

Rivers of Asia span glaciers, jungles, and deserts—discover their geography, biodiversity, cultural roots, and growing environmental threats.

Asia is a continent of extremes—home to the world’s highest peaks, deepest jungles, driest deserts, and coldest inhabited regions. It is also a continent defined by rivers. From the ice-fed arteries of the Himalayas to the monsoon-charged torrents of Southeast Asia, rivers in Asia have carved landscapes, birthed civilizations, and woven cultural identities for millennia. Today, they are lifelines for over half of humanity.

But these mighty waters are more than tools of survival or engines of agriculture—they are wild, beautiful, sacred, and threatened. In this post, we explore the geographical wonder and ecological richness of Asia’s rivers, tracing their stories from icy sources to fertile deltas.

Geography & Geology: A Continent of Contrasts

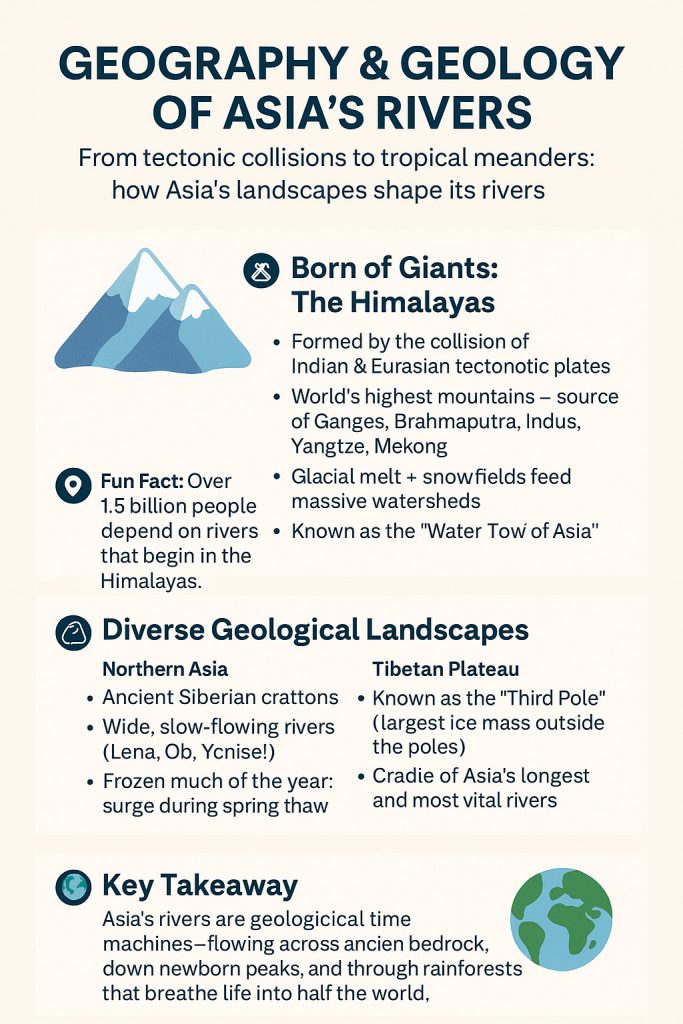

Asia’s rivers are forged in the crucible of continental collisions—born from the grinding force of tectonic plates that continues to reshape the land. Nowhere is this more evident than in the towering Himalayas, the world’s youngest and mightiest mountain range, formed by the ongoing convergence of the Indian and Eurasian plates. This titanic clash lifted ancient seabeds into sky-scraping peaks and created the high-altitude crucibles from which many of Asia’s greatest rivers flow.

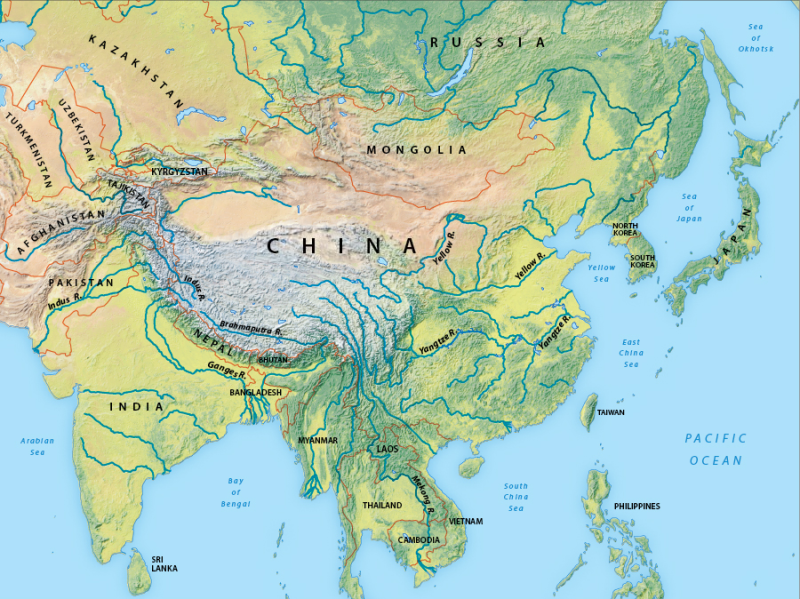

From these icy summits, meltwater from glaciers and snowfields spills into deep valleys and carves its way through sheer gorges. Here lie the headwaters of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, Yangtze, and Mekong—rivers that do not simply flow through countries but define them. They nourish hundreds of millions, shape mythologies, and chart the contours of empire and ecology alike.

Yet the story of Asia’s rivers doesn’t begin and end in the Himalayas. Geologically, the continent is a patchwork of extremes. In the north, Siberian rivers like the Lena, Ob, and Yenisei course across the ancient and stable East European and Siberian cratons, flowing through boreal taiga, tundra, and landscapes locked in permafrost for most of the year. These are slow, meandering giants, swollen with snowmelt and glacial runoff during the brief but explosive Arctic spring.

In the east and southeast, young volcanic highlands—like those of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Japan—birth fast-moving rivers that race through jungle-cloaked slopes, prone to sudden floods and fertile eruptions. Rivers in Borneo, for example, wind lazily through lowland equatorial rainforest, supporting some of the richest freshwater biodiversity on Earth, their dark, tannin-stained waters brimming with life.

The Tibetan Plateau, often called the “Third Pole” due to its immense ice reserves, serves as a vast hydrological engine. It supplies water to rivers that sustain over a third of the world’s population, making it one of the most geopolitically critical regions on the planet.

Asia’s rivers are sculptors, carving not only land but legacy. From the glacial thunders of the Hindu Kush to the slow, steamy tides of the South China Sea, they reflect the continent’s geological youth, its ancient foundations, and its ever-changing face.

🌋 Born from the Collision of Continents

Asia’s vast and complex river systems are the direct result of deep geological forces. The Indian tectonic plate continues to push northward into the Eurasian plate at a rate of about 5 cm per year—a slow-motion collision that began around 50 million years ago and created the Himalayas, the Tibetan Plateau, and the highest concentration of high-altitude river sources on the planet.

This region is often referred to as Asia’s Water Tower and contains the headwaters of ten major rivers. These rivers—among them the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, Yangtze, Yellow River, Mekong, Salween, and Irrawaddy—support nearly 3 billion people downstream.

- Tibetan Plateau area: ~2.5 million km²

- Average elevation: over 4,500 meters (14,800 feet)

- Glacier count: Over 46,000 glaciers feed the river systems of Asia

- Annual freshwater discharge from Himalayan rivers: Over 1,500 km³/year

🧱 Geological Diversity Across the Continent

Asia’s rivers traverse a continent of unmatched geological contrasts, which explains the extraordinary variety in river shape, sediment load, flow regime, and ecology.

| Region | Geological Type | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Tibetan Plateau | Uplifted terrane, glaciated highlands | Source of Asia’s largest rivers. Harsh, high-altitude climate. Deep gorges, tectonic valleys. |

| Siberian Craton | Ancient continental shield | Home to the Lena, Ob, and Yenisei. Rivers freeze over for 6–9 months a year. Massive spring floods. |

| Loess Plateau (China) | Wind-blown silts, soft sediments | Erosion-prone. Yellow River (Huang He) runs through here. High sediment load, braided channels, flash floods. |

| Southeast Asia Islands | Volcanic arc systems | Short but torrential rivers (e.g. Agusan, Mahakam). Rapid erosion, steep gradients, high rainfall zones, deeply incised gorges. |

| Central Asia | Arid basins and fault-block mountains | Endorheic basins (no outflow to sea), e.g., Amu Darya, Syr Darya. Former glacial rivers now often diverted or dried due to irrigation (e.g., Aral Sea). |

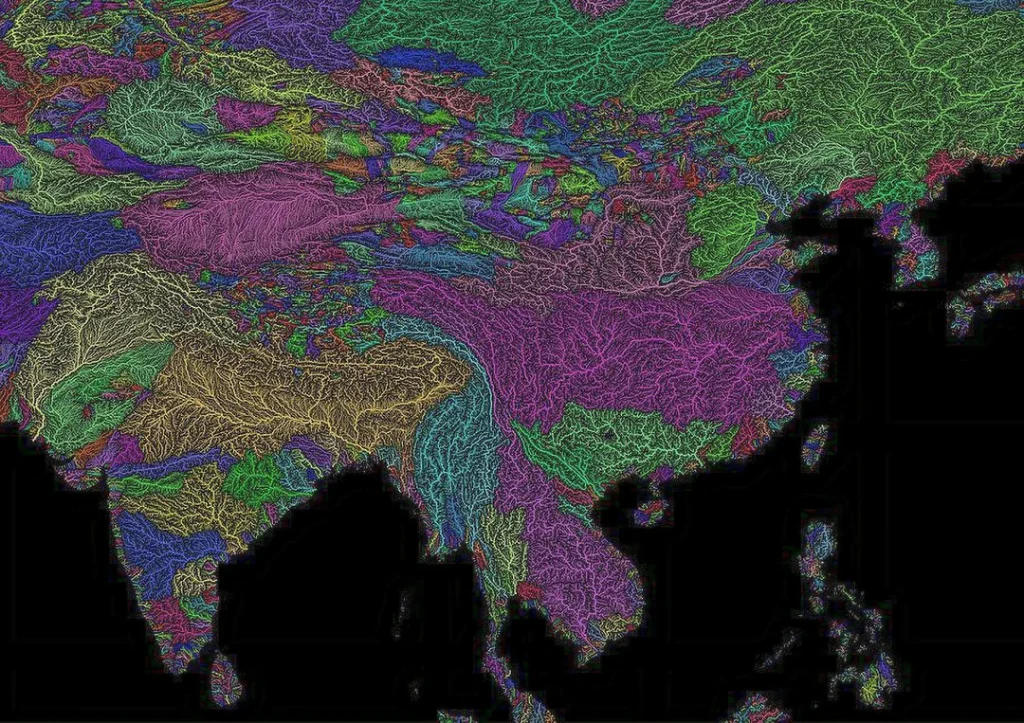

🗺️ Continental-Scale Drainage Patterns

Asia’s rivers drain into three major oceans and one inland basin:

- Pacific Ocean: Yangtze, Yellow River, Amur, Mekong

- Indian Ocean: Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, Irrawaddy

- Arctic Ocean: Ob, Lena, Yenisei

- Endorheic Basins (no outlet to ocean): Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Tarim (feeds disappearing lakes like Aral and Lop Nor)

Major Drainage Basins and Catchments

Asia’s rivers do not flow randomly—they follow the contours of the land, carving immense basins that have shaped the destiny of civilizations and ecosystems alike.

Asia’s river systems drain into three of the world’s major oceans—the Pacific, Indian, and Arctic—and also into internal, endorheic basins with no outlet to the sea. Together, they sculpt some of the largest and most ecologically and economically vital catchment areas on Earth.

🗺️ Continental-Scale Drainage Patterns

Asia’s rivers drain into three major oceans and one inland basin:

- Pacific Ocean: Yangtze, Yellow River, Amur, Mekong

- Indian Ocean: Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, Irrawaddy

- Arctic Ocean: Ob, Lena, Yenisei

- Endorheic Basins (no outlet to ocean): Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Tarim (feeds disappearing lakes like Aral and Lop Nor)

🌐 Surface Area, Flow & Significance of Major Basins

| River | Length (km) | Basin Area (km²) | Annual Discharge (km³) | Countries Traversed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yangtze | 6,300 | ~1,800,000 | ~1,000 | China |

| Ganges-Brahmaputra | ~3,000–2,900 ea. | ~1,700,000 combined | ~1,200 | India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Tibet |

| Mekong | 4,350 | ~795,000 | ~475 | China, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam |

| Indus | 3,180 | ~1,165,000 | ~208 | China, India, Pakistan |

| Lena | 4,400 | ~2,500,000 | ~520 | Russia |

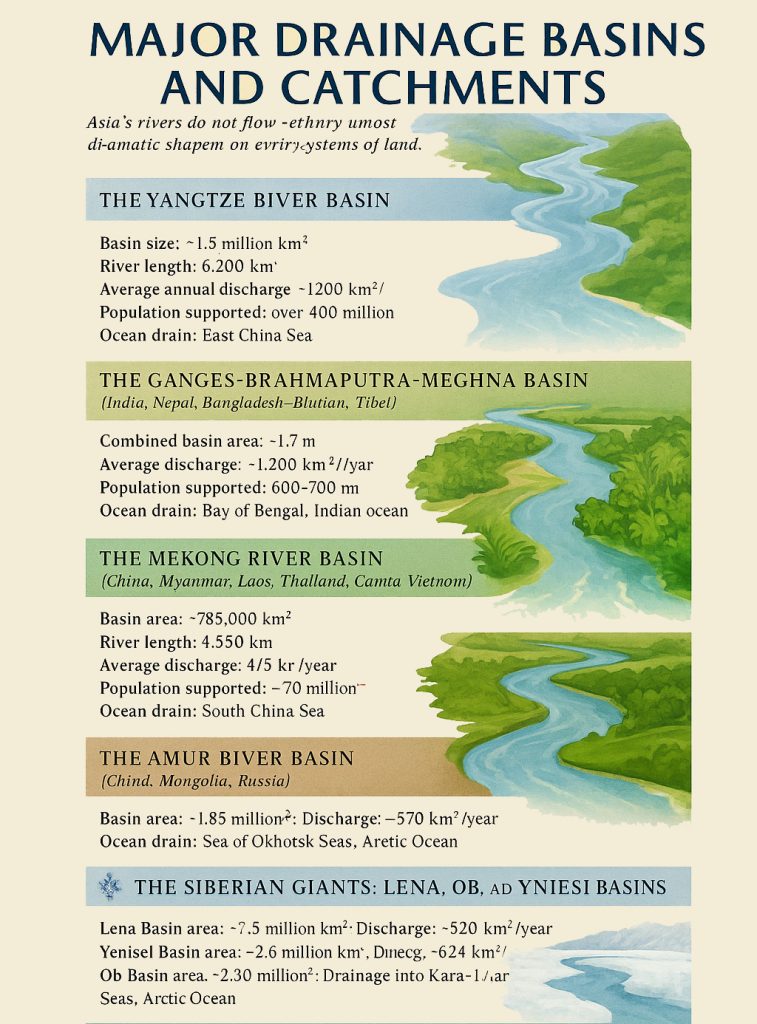

The Yangtze River Basin (China)

- Basin size: ~1.8 million km²

- River length: 6,300 km

- Average annual discharge: ~1,000 km³

- Population supported: Over 400 million

- Ocean drain: East China Sea (Pacific)

The Yangtze River (Chang Jiang) is the longest river in Asia and the third-longest in the world. It originates on the Tibetan Plateau and slices through deep gorges, fertile plains, and megacities before emptying into the Pacific. It is the industrial and agricultural backbone of China, as well as a biodiversity hotspot for endemic species like the Yangtze sturgeon and Chinese paddlefish (sadly presumed extinct).

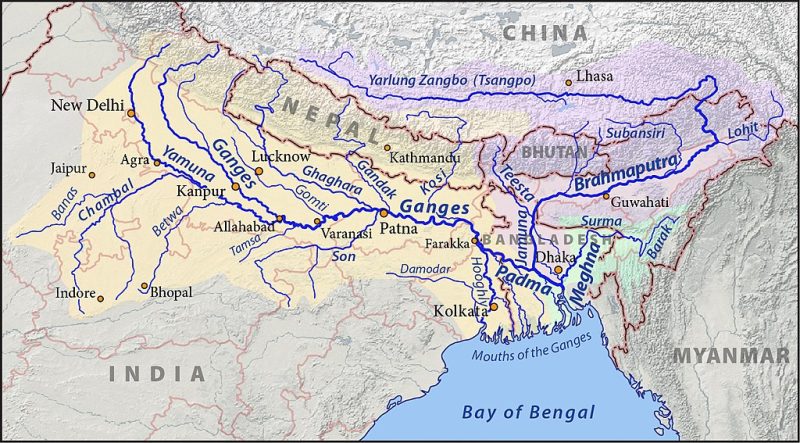

🟨 2. The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Basin (India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Tibet)

- Combined basin area: ~1.7 million km²

- Average discharge (combined): ~1,200 km³/year

- Population supported: 600–700 million

- Ocean drain: Bay of Bengal (Indian Ocean)

This is one of the most densely populated river basins on Earth. The Ganges and Brahmaputra originate in the Himalayas and meet in Bangladesh, forming the largest delta in the world—the Sundarbans Delta, home to vast mangrove forests and Bengal tigers. This basin is not only agriculturally productive but deeply sacred in Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic traditions.

Follow the Flow: India’s Mighty Rivers Unveiled

🟩 3. The Mekong River Basin (China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam)

- Basin area: ~795,000 km²

- River length: 4,350 km

- Average discharge: ~475 km³/year

- Population supported: ~70 million

- Ocean drain: South China Sea (Pacific)

From the Tibetan Plateau to the Mekong Delta, this river winds through some of the most biodiverse and agriculturally critical landscapes in Southeast Asia. The basin supports the world’s largest inland fishery, and the river’s flow is controlled by seasonal monsoons. Its ecology is threatened by upstream dams and sand mining.

🟫 4. The Amur River Basin (China, Mongolia, Russia)

- Basin area: ~1.85 million km²

- River length: 4,444 km

- Average discharge: ~340 km³/year

- Population supported: ~75 million

- Ocean drain: Sea of Okhotsk (Pacific)

Flowing through taiga and temperate forests, the Amur River (called Heilong Jiang in Chinese) is one of the longest undammed rivers in Asia. It marks a long stretch of the Russia–China border and boasts an impressive array of endemic species, including the endangered Amur leopard and Kaluga sturgeon.

❄️ 5. The Siberian Giants: Lena, Ob, and Yenisei Basins (Russia)

- Lena Basin area: ~2.5 million km² | Discharge: ~520 km³/year

- Yenisei Basin area: ~2.6 million km² | Discharge: ~624 km³/year

- Ob Basin area: ~2.99 million km² | Discharge: ~470 km³/year

- Combined drainage into: Kara and Laptev Seas (Arctic Ocean)

These colossal rivers flow northward through frozen Siberian tundra, much of it underlain by permafrost. They experience intense spring floods due to ice jams and snowmelt, and their estuaries and deltas are some of the last relatively untouched wetland ecosystems on the planet. The Yenisei is the most voluminous river system draining into the Arctic.

🏔️ Catchment Origins & Hydrological Rhythms

Asia’s catchments are governed by one of three primary water sources:

| Source Type | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Glacial Melt | Dominant in the Himalayas, Hindu Kush, and Tibetan Plateau. Year-round flow sustained by melting ice. |

| Snowmelt-Driven | Common in Central and Northern Asia. Strong seasonal pulses (e.g., Lena, Amu Darya). |

| Monsoon-Fed | Southern and Southeast Asia. High variability and strong wet-season peaks (e.g., Mekong, Ganges). |

Catchments range from the ice-bound Pamirs, through loess plains, rainforests, and rice paddies, down to mangrove-lined deltas.

🧭 Final Insight: Rivers as Continental Arteries

Asia’s major drainage basins are more than hydrological phenomena—they are cradles of life and culture, epicenters of biodiversity, and indicators of planetary change. Understanding their size, sources, and flow patterns is key to grasping how water shapes everything from agriculture and food security to geopolitics and climate resilience.

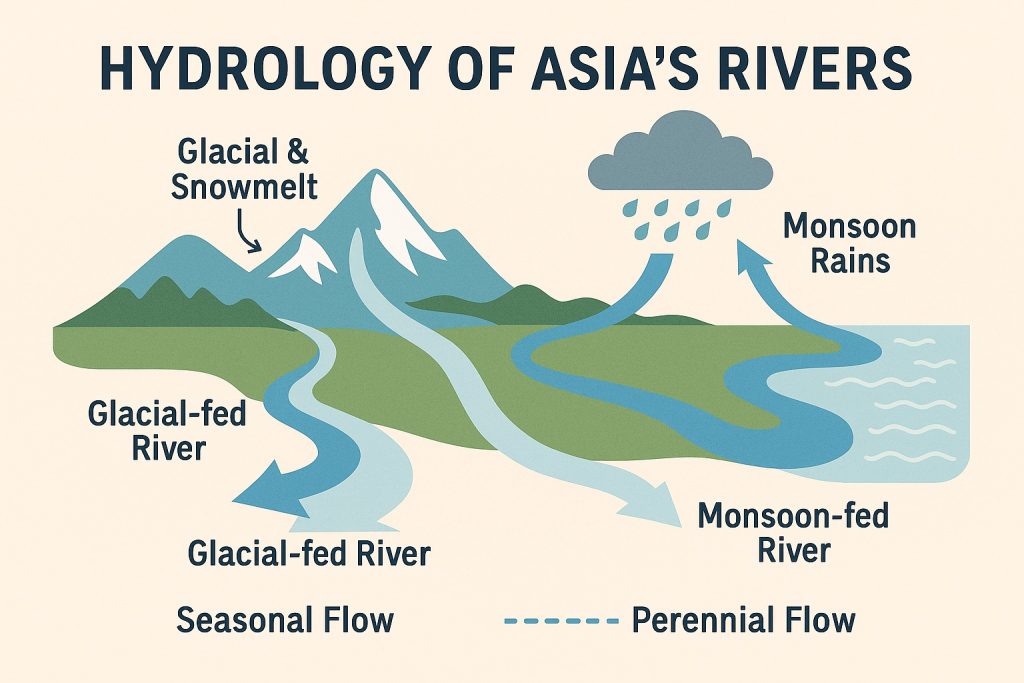

Hydrology: The Pulse of Asia’s Rivers

Beneath every river’s flow is a rhythm—a hydrological heartbeat that pulses with meltwater, monsoons, and ancient rain cycles. In Asia, this rhythm is as varied as the landscapes the rivers pass through, from the permafrost-bound north to the tropical floodplains of the south.

💧 Discharge: A Measure of Power

The rivers of Asia discharge an extraordinary volume of freshwater into surrounding seas and oceans. The Ganges-Brahmaputra system, for instance, releases over 1,200 km³ of water annually, making it one of the most voluminous systems on Earth. The Yangtze, despite flowing entirely within China, delivers approximately 1,000 km³/year, fueling the heart of the country’s economy and ecosystems. In contrast, rivers like the Yellow River carry a much smaller volume—due not only to regional aridity but also to sedimentation, water extraction, and dam regulation.

Northern rivers such as the Lena, Ob, and Yenisei may appear frozen and lifeless for much of the year, but during spring melt, their flow increases dramatically—accounting for some of the largest seasonal surges in global freshwater discharge, much of it flowing into the Arctic Ocean.

🌦️ Seasonal Patterns: Glacial Pulse and Monsoon Surge

Asia’s rivers are largely governed by two dominant hydrological engines:

- Glacial and snowmelt from the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau

- Monsoonal rainfall in the south and southeast

In the highlands, rivers such as the Indus, Brahmaputra, and Yangtze are sustained year-round by glacial melt, with discharge peaking during the summer months when snow and ice retreat under the sun’s warmth. This glacial pulse ensures flow even during dry seasons but also makes the region vulnerable to climate-induced glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs).

In contrast, monsoonal rivers such as the Mekong, Irrawaddy, and Ganges see extreme variability between dry and wet seasons. The Southwest Monsoon, typically arriving in June, unleashes torrents of rain that raise water levels dramatically, often triggering floods. By October or November, many of these rivers return to a low-flow state, with exposed sandbanks, receding wetlands, and shrinking tributaries.

The northeast monsoon is contributing to reverse flows in the delta’s distributaries. Flood pulses are essential for replenishing floodplains, rice paddies, and fisheries—but extreme variation is becoming more common, with both droughts and floods increasing in intensity.

🏜️ Ephemeral and Intermittent Rivers

Not all rivers in Asia flow year-round. In Central Asia, particularly in the interior deserts of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, rivers such as the Zarafshan, parts of the Amu Darya, and many smaller streams are intermittent—flowing only during spring melt or after heavy rains.

Ephemeral rivers, which flow briefly after rare rain events, are also found in arid basins across western China and the Thar Desert of India and Pakistan. These channels may remain dry for months or years, but when they do awaken, they reshape landscapes with flash floods and sudden erosion.

Even perennial rivers are increasingly behaving like intermittent ones due to overextraction, dam regulation, and climate variability—a striking example being the Amu Darya, which now often fails to reach its natural mouth at the Aral Sea.

River Ecology: From Frozen Tundra to Steamy Tropics

Asia’s rivers are more than water—they are living corridors, flowing through the veins of every ecosystem from the Arctic Circle to the equator.

Asia is home to some of the most diverse riverine ecosystems on Earth, spanning an astonishing range of climatic and ecological zones—from permafrost-laced floodplains to mangrove-choked deltas, alpine torrents to meandering rainforest rivers. These freshwater habitats provide critical lifelines for thousands of species—many of them endemic, endangered, or found nowhere else.

❄️ Arctic & Subarctic River

Examples: Ob, Lena, Yenisei (Russia)

For much of the year, the mighty Siberian rivers lie locked beneath ice, their surfaces silent and crystalline. But come spring, the thaw transforms them into surging lifelines. These permafrost-fed rivers support immense floodplain wetlands—seasonal oases for migratory birds such as geese, cranes, and ducks traveling along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway.

- Key species:

- Arctic char, grayling, Siberian sturgeon

- Reindeer, which follow seasonal grazing routes

- Muskoxen, brown bears, and boreal amphibians in surrounding taiga

- These rivers play a critical role in carbon sequestration through their peatlands and wet meadows.

🌳 Temperate Rivers

Examples: Amur, Yellow River (China and Russia)

Flowing through forests, steppe, and rolling grasslands, these rivers thread through temperate biodiversity hotspots. The Amur River, for instance, is one of the last free-flowing major rivers in Asia and harbors some of the most iconic endangered species.

- Key species:

- Kaluga sturgeon (among the largest freshwater fish on Earth)

- Siberian tiger and Amur leopard

- Sakhalin taimen and wild boar

- Asian black bear, Japanese cranes

- These rivers are shaped by spring floods and moderate seasonal rains, creating productive agricultural plains and spawning grounds.

🌴 Tropical Rivers

Examples: Mekong (Southeast Asia), Kapuas (Indonesia)

Asia’s tropical rivers are ecological juggernauts, especially in monsoon-drenched Southeast Asia. Here, heavy seasonal rains swell rivers into vast floodplains, oxbow lakes, and braided streams, transforming landscapes with astonishing speed and fertility.

The Mekong River, for example, is home to over 1,100 species of fish—second only to the Amazon in freshwater biodiversity. The Kapuas River in Borneo supports some of the richest lowland rainforest ecosystems in the world.

- Key species:

- Giant freshwater stingray, Mekong giant catfish, Irrawaddy dolphin

- Proboscis monkeys, orangutans, hornbills, and crocodiles

- Aquatic plants, snails, and mollusks unique to seasonal wet zones

- Local communities depend on these ecosystems for rice farming, fisheries, and floating markets.

🏔️ Mountain Rivers

Examples: Indus, Yarlung Tsangpo, Brahmaputra headwaters

Racing down steep gradients from glaciers and snowfields, mountain rivers are high-energy ecosystems. Often beginning above 4,000 meters in the Himalayas, they carve deep gorges, feed alpine meadows, and create dramatic microclimates. Their cold, oxygen-rich waters are ideal for trout and snow-fed invertebrates, while their glacial pulse determines downstream water availability for vast populations.

- Key species:

- Snow leopard, blue sheep, Himalayan marmots

- Golden mahseer and Himalayan snow trout

- Tibetan wolf, bearded vulture, and Himalayan newt

- These rivers are critical to hydropower, yet face rising threats from glacial retreat, landslides, and dam construction.

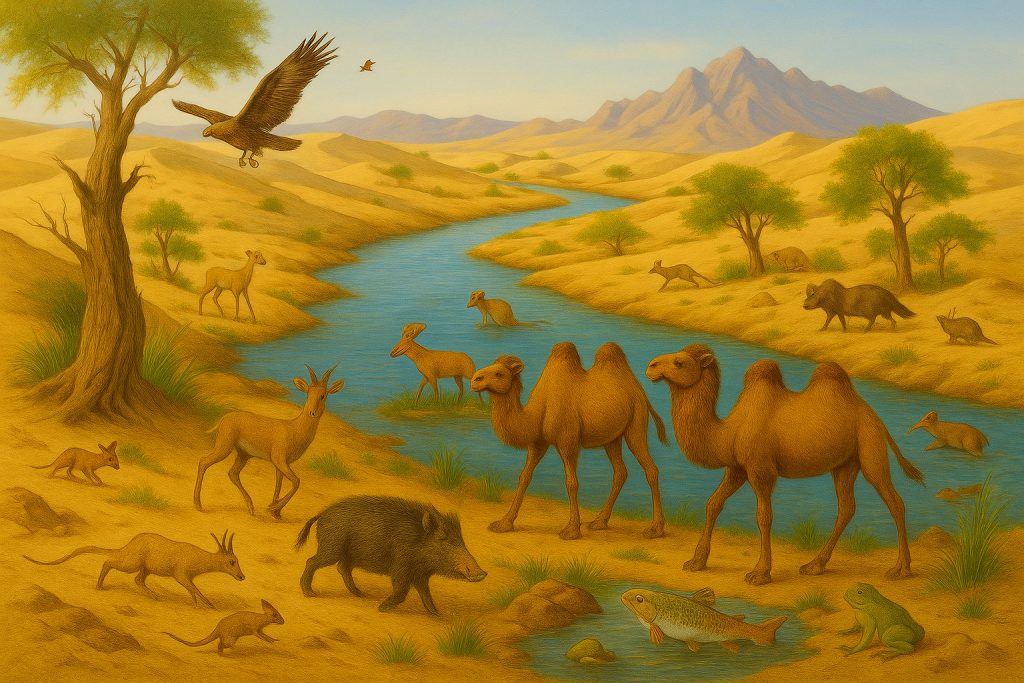

🏜️ Desert Rivers: Lifelines in the Sands

In the heart of Asia’s vast interior, desert rivers flow like green threads through gold. In Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, rivers such as the Amu Darya, Syr Darya, and Zarafshan originate in distant mountains but dwindle as they reach the arid plains, often consumed by irrigation or evaporation. The Amu Darya, once a powerful river, now rarely reaches its natural end at the Aral Sea.

Further east, China’s Tarim River winds through the Taklamakan Desert, sustaining scattered oases and ancient Silk Road towns. These inland rivers never reach the ocean, instead forming terminal lakes or drying into the sand. Flow is highly seasonal—fed by spring melt or rare storms—and some are intermittent or ephemeral, active only a few weeks a year.

Despite the harshness, these rivers support riparian forests, wild camels, gazelles, and hardy aquatic species adapted to saline, shallow waters. But desert rivers are increasingly fragile—overdrawn, diverted, and threatened by climate shifts. Their silence marks not just drought, but deep ecological imbalance.

- Key species:

- Bactrian camels, goitered gazelles, and jerboas in surrounding deserts

- Wild boars, steppe eagles, and amphibians clustered around oasis wetlands

- Endemic fish like Tarim schizothorax adapted to saline, shallow waters

- Flora: Salt-tolerant reeds, tamarisks, and desert poplars cling to riverbanks, forming a last green belt between dune and drought.

River Features: Sculptors of the Asian Landscape

From the world’s deepest canyon to sacred glacial springs, Asia’s rivers are not just waterways—they’re monuments of natural wonder, geological drama, and cultural reverence.

Asia’s river systems contain some of the most visually spectacular and geologically significant features on the planet. Shaped by tectonic forces, monsoon cycles, and glacial flows, these rivers leave behind unmistakable signatures—canyons that split the Earth, deltas that cradle entire nations, and terraces that speak the language of deep time.

🏞️ Canyons

One of the most awe-inspiring features formed by rivers are canyons, deep gashes in the Earth’s crust where water has cut through rock over immense timescales. The Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon in Tibet plunges deeper than the Grand Canyon itself, over 5,300 meters. The Indus River also courses through a dramatic gorge as it exits the Tibetan Plateau. The Salween, Yangtze, and upper Mekong similarly thunder through vertical-walled ravines, showcasing how rivers and tectonics intertwine in the Himalayan arc.

🌄 Valleys

Rivers often broaden into valleys, the arteries of agriculture and human settlement. The Ganges Valley is one of the most fertile and densely populated in the world. The Yellow River flows through the highly erodible Loess Plateau, creating steep-sided gullies and deep-cut ravines. Further west, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya flow through expansive valleys of Central Asia, carving oases from deserts and steppes.

🌊 Deltas

Where rivers meet the sea, deltas form—dynamic, sediment-rich landscapes shaped by water, tides, and time. The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Delta is Earth’s largest, covering over 105,000 km² and hosting the iconic Sundarbans mangrove forest. Other important deltas include the Mekong Delta in Vietnam and the Irrawaddy Delta in Myanmar, each vital for rice production and biodiversity. These zones are both productive and vulnerable, threatened by sea-level rise and reduced sediment from upstream dams.

🌅 Estuaries

In some regions, rivers do not fan out into deltas but instead form estuaries—funnel-shaped mouths where freshwater mixes with tidal seawater. The Yangtze Estuary is one of the busiest maritime zones on Earth and still harbors wetland sanctuaries like Chongming Island. The Pearl River Estuary is home to both massive ports and delicate mangrove ecosystems. Estuaries often serve as transition zones rich in life, trade, and sediment exchange.

❄️ River Sources

Asia’s rivers rise in dramatic, often sacred, places. The Tibetan Plateau—dubbed the Third Pole—feeds most of the continent’s major rivers, including the Indus, Yangtze, Brahmaputra, and Mekong. Sources are typically glacial lakes, such as Lake Manasarovar, or high mountain snowfields and springs like the Gangotri Glacier. These headwaters are under threat from climate change, glacial retreat, and shifting monsoon patterns.

🌀 Meanders

As rivers descend into flatter terrain, they begin to meander, forming elegant curves and oxbow lakes. The Mekong River carves broad, looping arcs through Laos and Cambodia. In Assam, the Brahmaputra flows in a vast braided and meandering course, shifting unpredictably during floods. Even the Yellow River, despite its sediment-heavy flow, forms pronounced bends in its middle reaches.

🪵 River Terraces & Floodplains

River terraces—step-like features on valley walls—are remnants of ancient flood levels or tectonic uplift. The Indus Valley, Ganges foothills, and Yarlung Tsangpo basin feature prominent terraces, often used today for farming. In contrast, floodplains like those of the Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, and Red River are low-lying areas seasonally enriched by silt, making them ideal for rice cultivation and settlement.

🧭 Other Geomorphological Features

Asia’s rivers display additional unique traits. The Yellow River carries such a heavy sediment load that in places its bed lies above the surrounding land, confined by levees—a “suspended river.” In mountain areas, braided channels are common, such as along the Shyok or Sutlej, where meltwater and debris create constantly shifting paths. At the base of mountain ranges, rivers form alluvial fans, like those in northern India and Xinjiang, spreading sediment in broad, conical shapes.

Culture & Civilizations Along the Riverbanks

From the first bricks of empire to the drifting lanterns of modern festivals, rivers in Asia have shaped not only the land, but the very fabric of human life. Along their banks, civilizations were born. Along their currents, gods, goods, and ideas have long traveled.

In South Asia, the Indus River cradled the ancient Harappan civilization, one of the world’s earliest urban cultures. Grid-planned cities like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa rose beside its waters more than 4,000 years ago, thriving on trade, agriculture, and engineering. To the east, the Ganges is far more than a source of water—she is Ganga Ma, the river goddess, a living deity to hundreds of millions. Pilgrims still bathe in her waters for spiritual purification, cremate loved ones on her ghats, and celebrate her with flame-lit rituals like Ganga Aarti.

In East Asia, the Yangtze and Yellow River (Huang He) gave rise to Chinese civilization, feeding dynasties and philosophies. The Yellow River, often called “China’s sorrow” for its devastating floods, was also revered as the Mother River, nourishing the millet-based societies of the north. The Yangtze, meanwhile, became the backbone of southern China’s wet rice culture, and a historic waterway linking emperors, merchants, and poets alike.

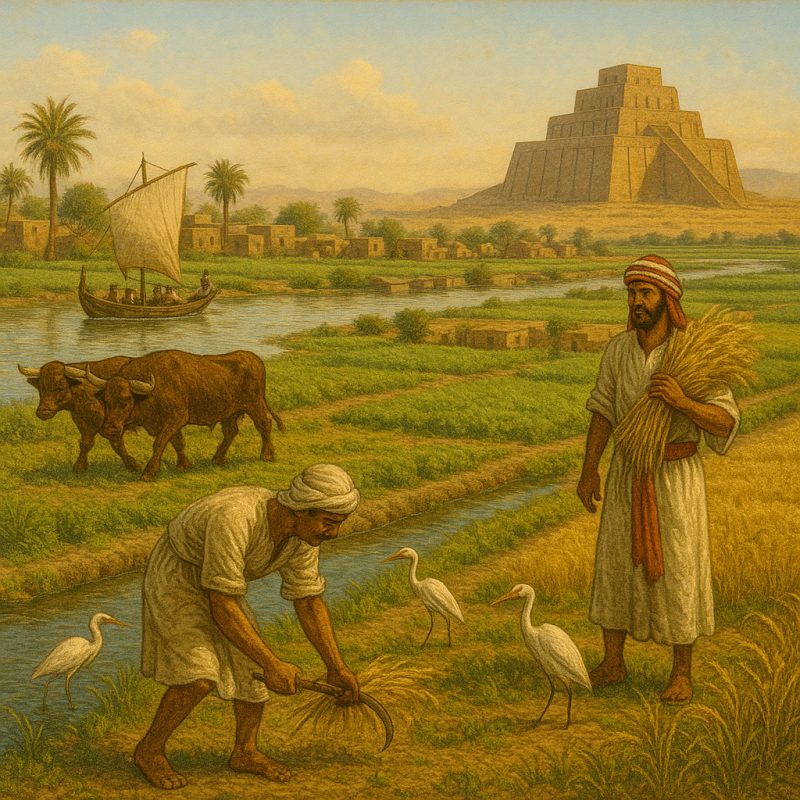

Farther west, in the lands now known as Iraq, Syria, and southeastern Turkey, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers nurtured Mesopotamia, often regarded as the birthplace of written language, law, and urban society. From Uruk to Babylon, their floodplains supported legendary cities whose echoes remain in clay tablets and ziggurat ruins.

In Central Asia, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya once flowed boldly through desert sands, guiding Silk Road caravans across perilous trade routes. Nomads camped by their bends, monks built monasteries nearby, and merchants carried spices, silk, and stories between East and West. Ancient cities like Samarkand and Bukhara owed their survival to these shifting yet life-giving rivers.

In Southeast Asia, rivers like the Mekong, Chao Phraya, and Irrawaddy pulse with both commerce and culture. In Vietnam and Thailand, floating markets glide atop wide delta channels, while fishermen still cast conical nets by hand. Riverbanks are adorned with temples, shrines, and stilt villages, and seasonal floods are welcomed as sacred gifts. Festivals like Songkran in Thailand (the water-splashing New Year) and Chhath Puja in India (sun worship at riverbanks) reveal a profound reverence for rivers as givers of life and spirit.

From high mountain hermitages to teeming delta megacities, Asia’s rivers remain the arteries of culture, memory, and meaning. To live by a river in Asia has always meant more than survival—it means connection to ancestry, divinity, and the eternal rhythms of the Earth.

Threats and Conservation Challenges

Once worshipped, now wounded—Asia’s rivers are facing their greatest crisis in millennia.

Asia’s rivers have long been revered as sources of life, spirit, and civilization. But today, these lifelines are increasingly endangered—squeezed, siphoned, and suffocated by human demand and environmental change. Across the continent, rivers that once flowed wild and sacred are being reshaped beyond recognition.

⚙️ Damming and Diversion

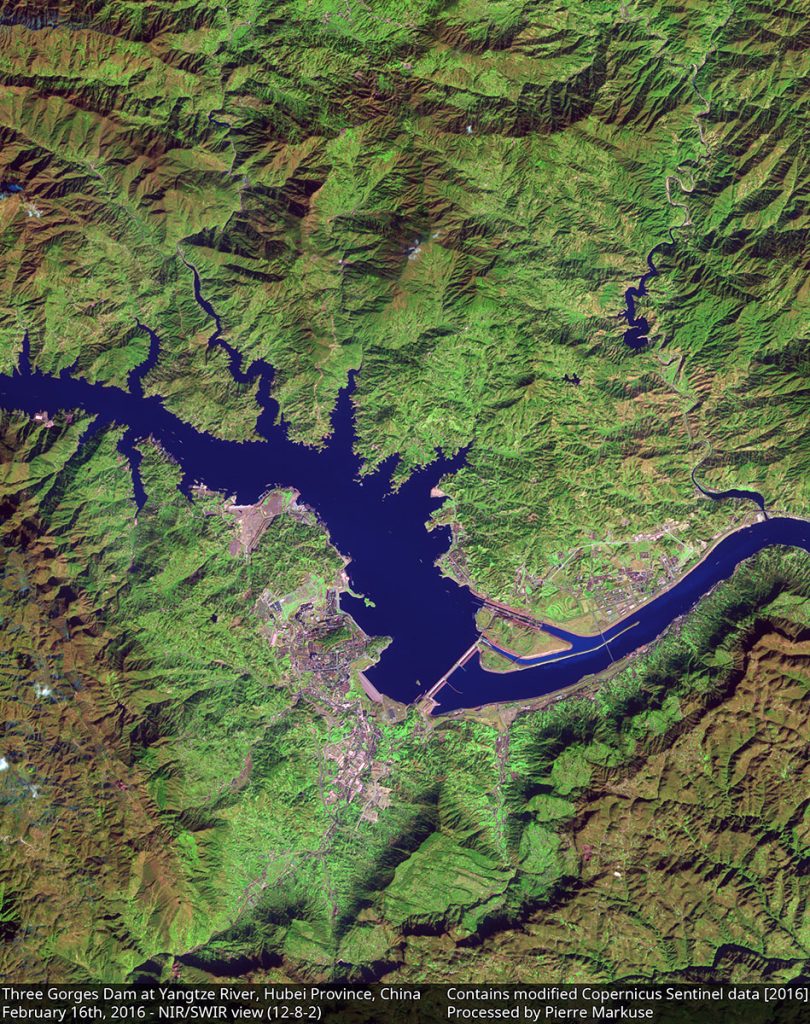

Perhaps the most dramatic transformation comes from hydrological engineering. Dams—often symbols of progress—have fragmented river systems, altered seasonal flows, submerged ecosystems, and blocked the natural migration of fish. The Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze is a striking example: the world’s largest hydroelectric project, it displaced over a million people, flooded ancient cultural sites, and drastically changed sediment delivery to the East China Sea.

Similar projects on the Mekong, Indus, Brahmaputra, and Salween threaten both biodiversity and the livelihoods of downstream communities. Water diversion schemes, often designed for irrigation or city supply, now siphon entire rivers dry—like the Amu Darya, which no longer reaches the Aral Sea in most years.

🧪 Pollution

Many of Asia’s rivers are now among the most polluted in the world. In rapidly urbanizing regions, rivers are treated more as drains than sacred flows. Untreated sewage, industrial effluents, and agricultural runoff contaminate river water with toxins, heavy metals, microplastics, and pathogens.

The Yamuna River in India, the Citarum in Indonesia, and stretches of the Yellow River in China have become warning signs of ecological collapse. In some areas, river water is no longer safe for bathing, let alone drinking or fishing. Plastic waste chokes deltas and estuaries, where tides concentrate humanity’s disregard.

⚠️ Overexploitation: Sand, Fish, and More

Rivers are not just water—they carry life and landscape. But the unregulated extraction of sand and gravel from riverbeds is accelerating erosion, collapsing banks, and altering flow patterns. The Mekong, once a majestic ribbon of biodiversity, is now being hollowed from below.

Overfishing, especially in the lower Mekong and Ganges basins, has depleted fish stocks to critical levels. Traditional riverine economies—dependent on small-scale fishing, basket traps, and seasonal harvests—are being replaced by mechanized trawling and invasive aquaculture.

🌡️ Climate Change

Asia’s rivers are highly vulnerable to climate instability. The monsoon, which governs rainfall across much of the continent, is becoming more erratic—bringing longer droughts, more intense floods, and shifting seasonal rhythms. Glaciers in the Himalayas, the source of many major rivers, are retreating rapidly, threatening both short-term floods and long-term water scarcity.

Sea-level rise and storm surges threaten deltas like the Ganges-Brahmaputra, where millions live just a few meters above water. Salinization of groundwater, loss of mangroves, and delta shrinkage are already displacing communities.

🧘♀️ Loss of Cultural and Ecological Identity

As the rivers change, so too do the stories they once inspired. Sacred sites are submerged, rituals abandoned, and languages forgotten. River-based communities—from fisherfolk in the Mekong Delta to nomads on the Amu Darya—are watching their way of life dissolve. What was once ritual is now resource; what was once wild is now regulated.

The loss isn’t just ecological—it’s cultural and spiritual. River festivals fade, traditional knowledge vanishes, and the deep human connection to flowing water is replaced by pipes, turbines, and satellite monitoring.

Conclusion

The rivers of Asia are as ancient as myth and as current as today’s news. They feed cities and fields, stories and spirits. But they are under threat. Preserving them requires honoring their complexity—from frozen headwaters to fertile mouths, from sacred stories to scientific insight. Only by seeing these rivers as living systems—not just water flowing through land—can we ensure their survival for generations to come.

🌄 Key River Features by Landscape Type

- Deepest Gorge: Yarlung Tsangpo (up to 5,500m deep)

- Sediment Load Champion: Yellow River – ~1.6 billion tons/year

- Widest Delta: Ganges-Brahmaputra – over 105,000 km²

- Oldest Craton Rivers: Lena and Ob – flow over Precambrian bedrock

- Fastest Declining: Amu Darya – now rarely reaches the Aral Sea