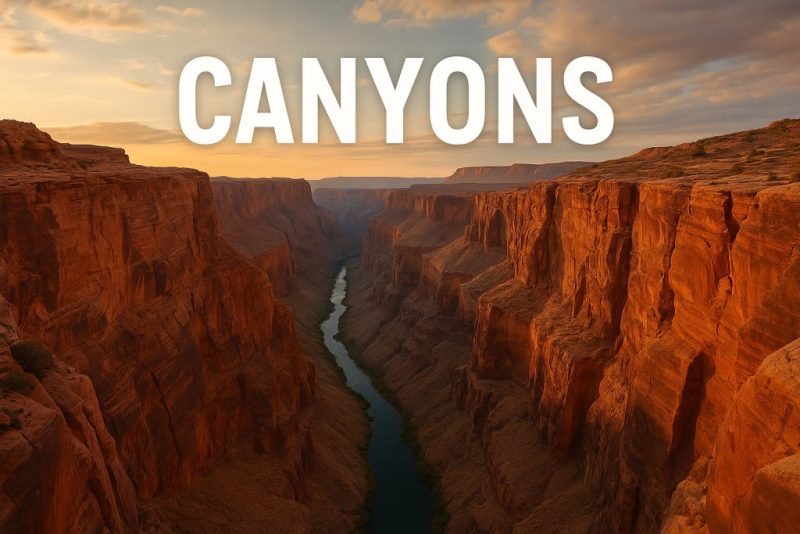

The Canyons: Towering Walls Above Life-Giving Rivers

Canyons are among the most dramatic river landscapes. Discover how they form—and where to find these towering wonders around the world.

Carved by the relentless power of water, canyons are nature’s grand corridors—deep, narrow valleys framed by towering walls that rise like ancient monuments above the rivers below. From the iconic Grand Canyon to hidden gorges across continents, these awe-inspiring landscapes tell a story of erosion, time, and transformation. In this post, we’ll explore how canyons form, the forces behind their dramatic shapes, and where in the world you can witness their breathtaking beauty.

Explore the valleys along the way.

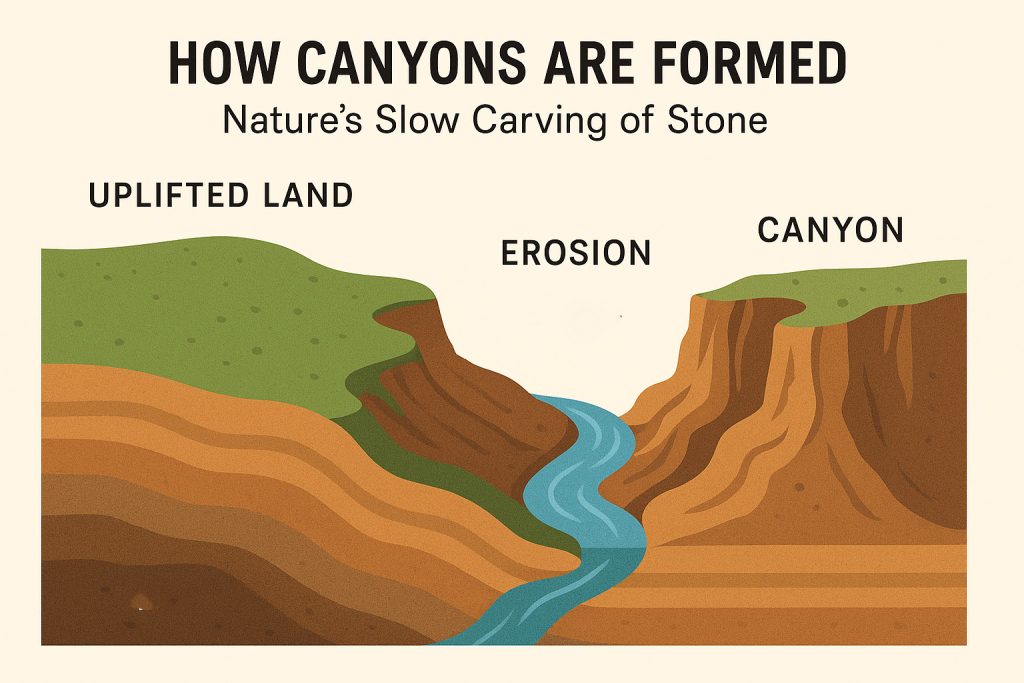

How Canyons Are Formed: Nature’s Slow Carving of Stone

Canyons are among the most dramatic results of river erosion—a slow, powerful process where water cuts deep into the Earth’s surface, sculpting rock over millions of years. At their core, canyons are a type of valley, but they stand apart in their scale and structure. While valleys tend to be broad and gently sloping, canyons are usually much deeper, narrower, and edged by steep, often vertical walls.

The process begins when a river or stream flows persistently over a region of uplifted land, gradually wearing away the bedrock beneath. As sediment and rock are carried downstream, the water carves deeper into the landscape, widening and extending the channel. Over time, this persistent erosion creates the sheer-sided chasms we recognize as canyons.

Though their appearance varies depending on the type of rock, climate, and tectonic activity, the underlying geological principle remains the same: rivers reshape the land from the inside out, creating some of the most awe-inspiring natural wonders on Earth.

Downcutting: How Rivers Carve Through Stone

The process of deepening a valley by eroding its streambed is called downcutting. This happens when a stream removes rock from its channel, gradually slicing through the landscape. In particularly resistant rock, this can lead to the formation of slot canyons—narrow, steep-walled gorges that descend sharply into the Earth.

However, slot canyons are relatively rare. That’s because other natural forces, like mass wasting (the downward movement of rock and soil) and sheet erosion (the removal of surface layers), tend to wear down the canyon walls. These processes gradually transform narrow, vertical canyons into broader, V-shaped valleys.

Slot canyons persist only under special conditions: where rock is extremely resistant, where fractures guide erosion vertically, or where downcutting is especially fast.

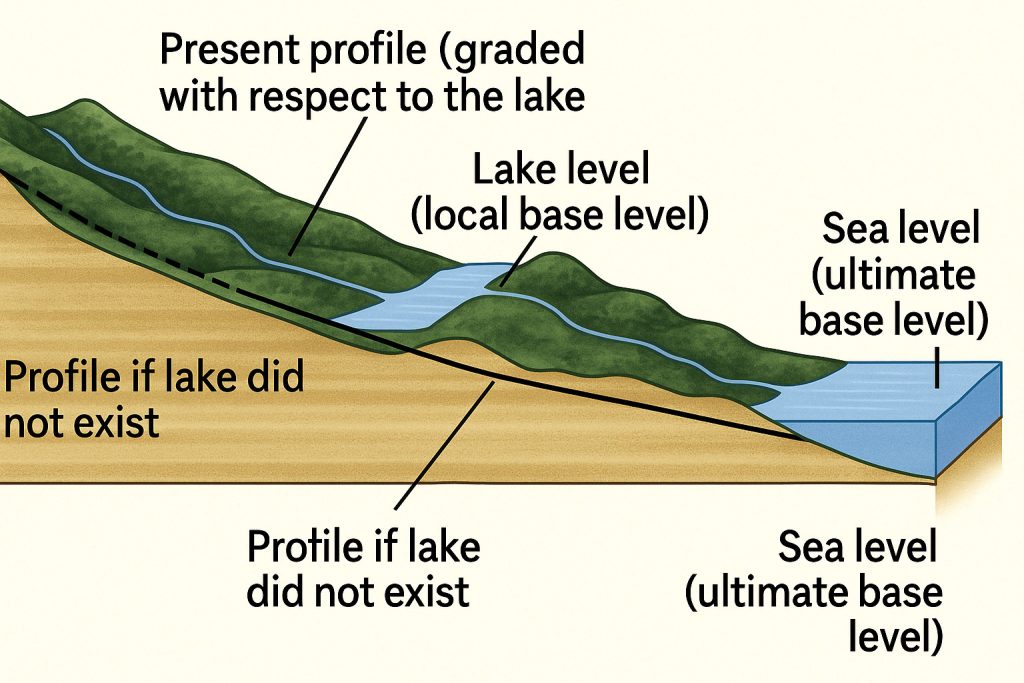

But downcutting has its limits. A stream cannot erode below the elevation of its mouth, where it meets a larger body of water like an ocean or lake. This lowest possible elevation is known as the base level. For most rivers, sea level is the ultimate base level—the point beyond which erosion cannot continue, because a river cannot flow uphill.

In essence, base level is the theoretical floor to which rivers can sculpt the land—a boundary that defines how deep a stream can cut, no matter how powerful its flow.

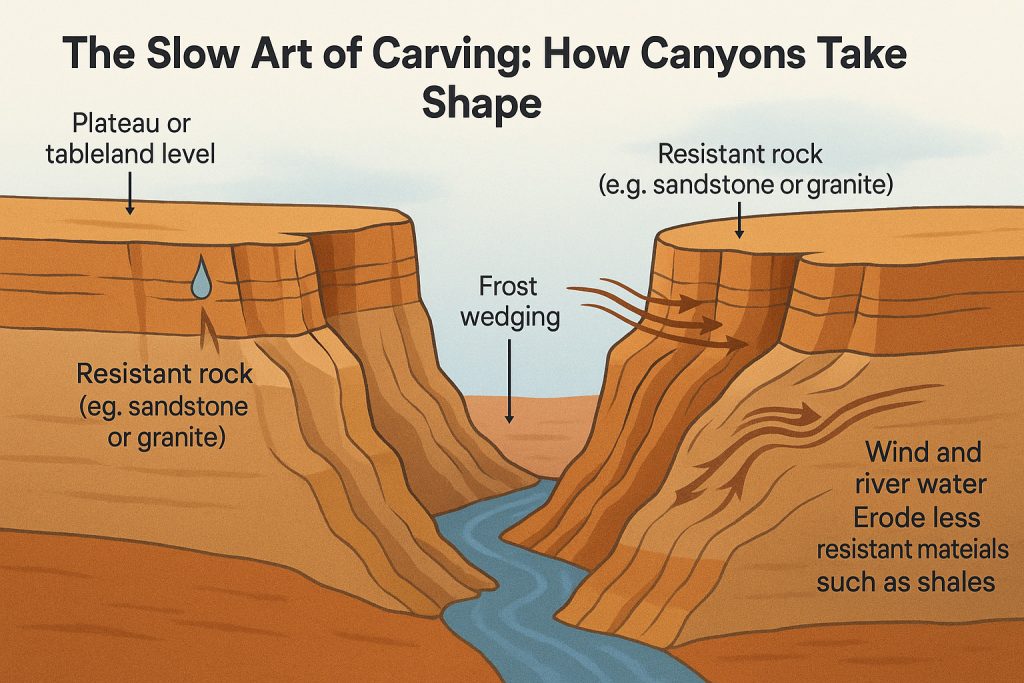

The Slow Art of Carving: How Canyons Take Shape

Canyon formation is a slow and powerful process—a patient sculpting of the land through millions of years of erosion. It typically begins on elevated terrain, such as a plateau or tableland, where rivers begin to cut downward through rock layers.

Cliffs form when harder, more erosion-resistant rock—like sandstone or granite—remains exposed on the canyon walls, while softer materials, such as shale, are gradually worn away. This contrast in rock strength gives canyons their iconic steep, layered appearance.

Canyons are more common in arid regions than in wetter ones, because physical weathering—caused by temperature extremes and minimal vegetation—has a more focused, localized effect in dry climates. Here, wind and river water work together to remove weaker rock and sediment.

One of the key mechanical forces in canyon development is frost wedging. When water seeps into tiny cracks in the rock and freezes, it expands—forcing the cracks wider. Over time, this can cause large chunks of rock to break away from the canyon walls, further deepening and shaping the chasm.

These valleys often form in the upper courses of rivers, where the stream has more energy to erode its bed and banks rapidly. But they’re also found in plains, particularly in areas underlain by softer, more easily eroded rock.

In the end, canyon walls stand as natural monuments—exposed layers of geologic history shaped by time, pressure, and the quiet persistence of wind, water, and ice.

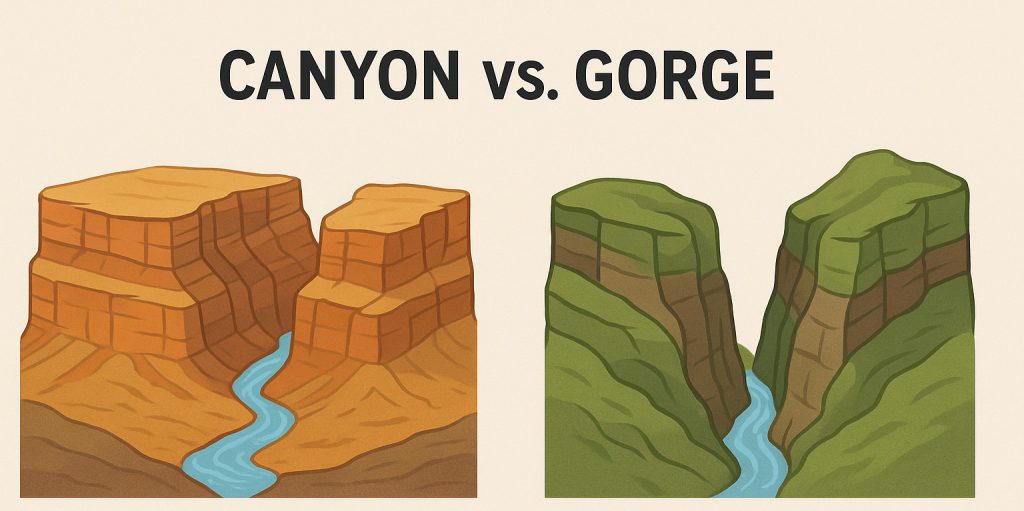

Canyon vs. Gorge: What’s the Difference?

While the terms canyon and gorge are often used interchangeably, there are subtle distinctions between the two.

A canyon is typically a large, deep valley with steep sides, often formed by long-term erosion from a river cutting through a plateau. Canyons are often wider and more expansive, with a more open, dramatic landscape. The word “canyon” is more common in North America, especially in the U.S. Southwest (e.g., the Grand Canyon).

A gorge, on the other hand, is usually narrower, steeper, and more enclosed. It often appears more rugged and vertical, sometimes resembling a slot canyon in extreme cases. Gorges are typically found in mountainous areas, where rapid water flow cuts through hard rock quickly. The term “gorge” is more commonly used in Europe (e.g., the Verdon Gorge in France).

In short:

-

Canyons = wider, often in dry plateaus, iconic and dramatic.

-

Gorges = narrower, steeper, often in wetter or mountainous terrain.

Dive into the world’s deepest canyons!

Canyons: Natural Fortresses and Oases in the Desert

Canyons often serve as natural fortresses for rivers, shielding them within steep, rugged walls that are difficult to traverse. These vertical cliffs and slopes of loose rock (known as scree) create a formidable barrier, protecting the river’s path from the surrounding terrain. In some regions, this isolation has preserved rare ecosystems and unique microclimates, turning the canyon floor into a hidden world.

In otherwise arid and barren landscapes, canyons can appear like unexpected oases. The river at the base provides a source of life—feeding plants, sustaining wildlife, and sometimes even supporting small communities. In these sheltered environments, you may find lush vegetation and cooler, more humid conditions compared to the sun-scorched land above.

At the same time, the geological structure of canyons makes them ideal locations for dam construction. Their narrow, steep-sided walls allow for efficient containment of water with relatively minimal engineering footprint. As a result, some of the world’s most significant dams—such as the Hoover Dam in the Black Canyon of the Colorado River—were built within canyons to harness hydroelectric power, manage water resources, and create reservoirs.

Thus, canyons play a dual role in the landscape: they are both shelters of natural wonder and strategic sites for human innovation.

Canyons as Natural Playgrounds: Adventure in the Heart of Stone

Beyond their geological grandeur, canyons offer thrilling opportunities for outdoor adventure. Their rugged terrain and winding river paths make them ideal settings for activities like whitewater rafting, hiking, climbing, and canyoning. Navigating a river through a narrow canyon with steep rock walls rising on either side is an unforgettable experience, especially where rapids churn between sculpted stone. Meanwhile, trails that follow the rim or descend into the canyon provide breathtaking views and access to hidden natural wonders—from waterfalls and rare plants to ancient rock formations. Whether you’re an adrenaline seeker or a nature lover, canyons are living playgrounds sculpted by time.

Kayaking on the Zrmanja River:

Canyons Around the World: Giants, Jewels, and Hidden Falls

Canyons exist on every continent, each one shaped by time, water, and rock into a landscape of breathtaking contrasts. Some are vast and iconic, others narrow and secretive, laced with waterfalls or glowing with layered stone. Here’s a glimpse into some of the world’s most remarkable canyons—from the deepest chasms to lush river gorges draped in mist.

🟥 Grand Canyon, USA

Perhaps the most famous canyon on Earth, the Grand Canyon stretches 446 km (277 miles) across the Arizona desert. Its vastness is staggering—up to 1,800 meters (6,000 feet) deep and sculpted in vivid reds, oranges, and golds. It’s not the deepest canyon, but its sheer scale and layered geological story are unmatched.

🏔 Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, Tibet

Often called the world’s deepest canyon, this remote wonder winds through the eastern Himalayas, with cliffs that plunge over 5,300 meters (17,000 feet). It’s a place few have explored, with intense whitewater and lush rainforest tucked between towering peaks.

💦 Krka River Canyon, Croatia

Flowing through Dalmatian karst country, the Krka River creates a gorge-like canyon lined with waterfalls, the most famous being Skradinski Buk. This emerald canyon is not only stunning—it’s also rich in biodiversity and historic watermills.

🍃 Verdon Gorge, France

Known as the “Grand Canyon of Europe,” the Gorges du Verdon is carved by the turquoise Verdon River and flanked by limestone cliffs up to 700 meters high. It’s a haven for hikers, climbers, and kayakers.

🌊 Fish River Canyon, Namibia

This African canyon is the second-largest in the world, stretching 160 km in length. Its stark, lunar landscape is breathtaking, especially at sunrise when the stone turns violet and rose-gold.

🌈 Antelope Canyon, USA

Unlike open canyons, Antelope is a slot canyon—a narrow passage with swirling, wave-like sandstone walls. Sunlight beams down in golden shafts, creating one of the most photographed natural wonders on Earth.

🏞 Colca Canyon, Peru

Twice as deep as the Grand Canyon, Colca Canyon plunges over 3,200 meters (10,500 feet) into the Andes. Its terraced slopes are still farmed today, and Andean condors soar dramatically over the gorge.

🌿 Tara River Canyon, Montenegro

Europe’s deepest canyon (up to 1,300 meters) is a protected UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, famed for its crystalline waters and wild rafting. It cuts through dense Balkan forest and is often shrouded in morning mist.

🌍 Did you know?

The term “canyon” comes from the Spanish word cañón, meaning “tube” or “pipe”—a reference to the narrow, deep shape of many canyons.

The deepest canyon in the world isn’t the Grand Canyon—it’s Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon in Tibet, which plunges over 5,300 meters (17,000 feet) deep in places!

Some canyons have unique ecosystems at their base, including fish and plant species that exist nowhere else due to the isolation and microclimate.

he Grand Canyon is so vast that it creates its own weather—temperature and storms at the bottom can differ drastically from those at the rim.The Colorado River through the Grand Canyon offers some of the best whitewater rafting in the world, with rapids classified up to Class V!

Some canyon walls are so tall and remote that parts of them have never been touched by human hands—and some sections still contain undiscovered archaeological sites.