Rivers of Australia: Catchments, Hydrology & Threats

Explore the rivers of Australia—from the Murray–Darling to tropical floodplains. Discover their hydrology, ecology, major catchments, and growing environmental threats.

Australia is a land of paradoxes: a sunburnt country with rivers that whisper rather than roar, flowing gently across one of the driest inhabited continents on Earth. Unlike the grand torrents of the Amazon or the seasonal drama of the Mekong, Australia’s rivers are shaped by age-old landscapes, erratic rainfall, and a fragile balance between life and desolation.

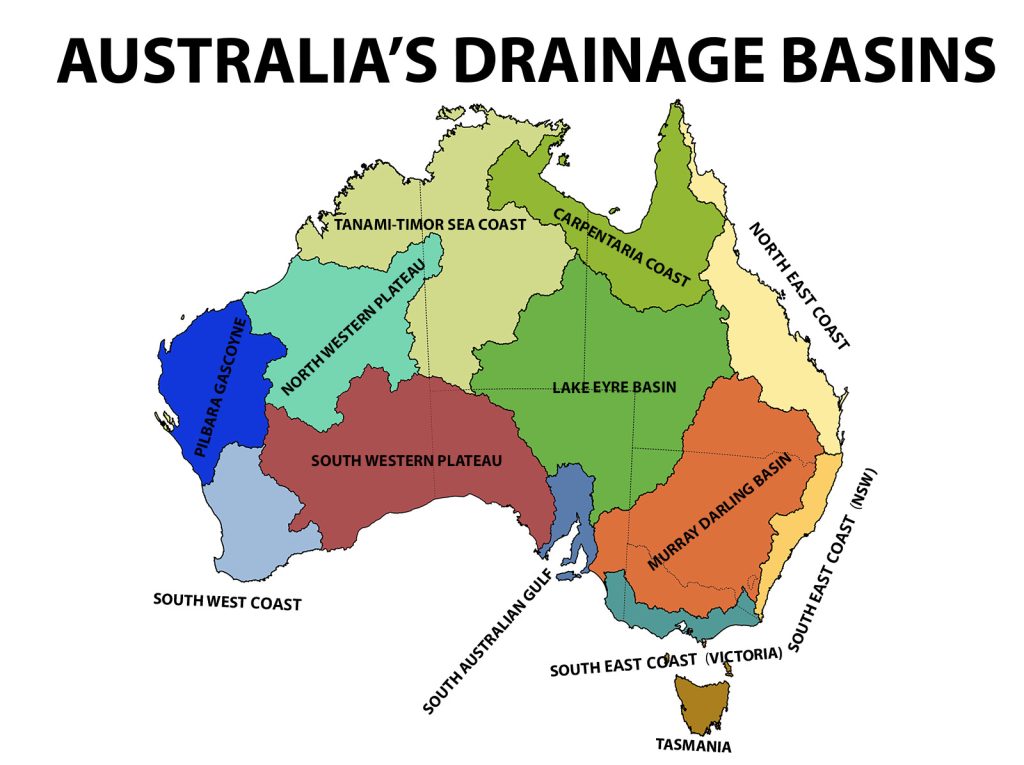

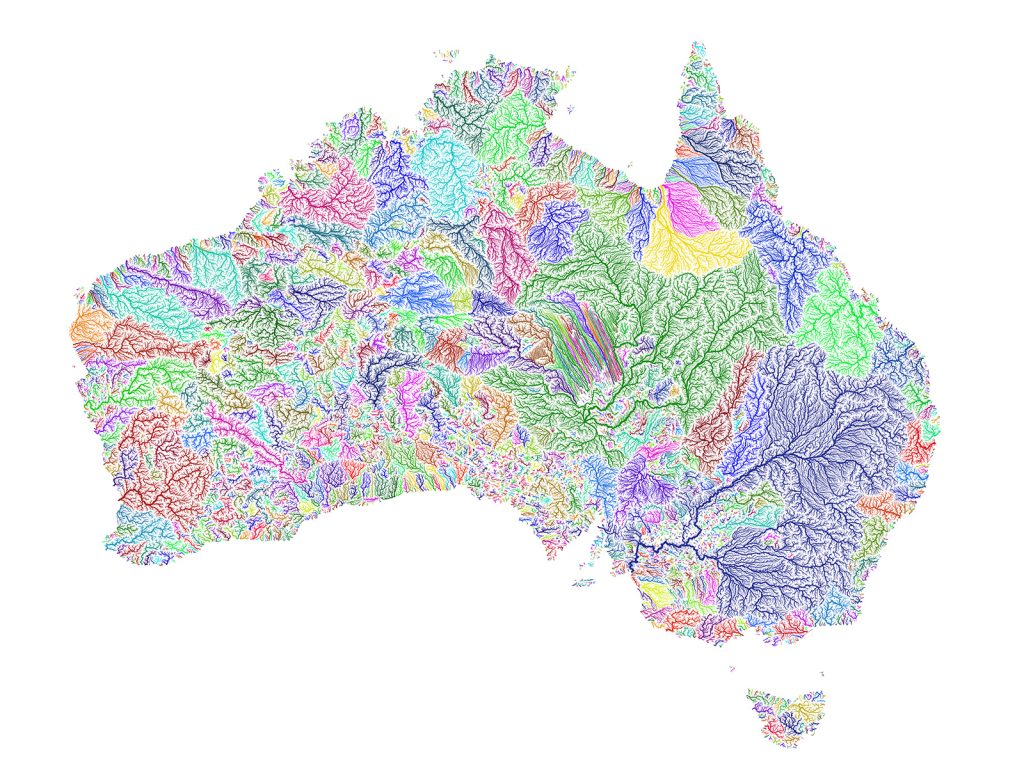

Australia’s drainage basins

Australia has thirteen major drainage divisions, each representing a unique hydrological landscape, as outlined in the Australian Water Resources Assessment 2010—a comprehensive survey conducted by the Bureau of Meteorology. These divisions are not just cartographic curiosities; they reflect the continent’s vast and varied geography, climate patterns, and water flow dynamics.

Covering everything from humid tropical coasts to the sun-scorched interior, these drainage divisions define where rainfall collects and ultimately flows. Depending on the terrain and climatic region, the water from these basins finds its way into one of four final destinations: the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, or, more rarely, into internal sinks like Lake Eyre—a vast salt lake that only fills during exceptional flood events.

Some, like the Murray–Darling Basin, support major agricultural zones and dense human settlement, while others such as the North Western Plateau or the Lake Eyre Basin are mostly dry for much of the year, with rivers that flow only occasionally in response to unpredictable desert rains. In tropical northern Australia, drainage divisions like the Gulf of Carpentaria or Timor Sea experience a strong monsoonal influence, with seasonal flooding driving dramatic ecological change.

This national classification system helps hydrologists, conservationists, and policymakers monitor and manage Australia’s scarce and unevenly distributed water resources. In a land where water is more limiting than land itself, understanding these divisions is essential for ensuring ecological sustainability, agricultural productivity, and the preservation of ancient waterways that have shaped life on the continent for millennia.

🏞️ Major Catchments: From Monsoon Tropics to Red Heart

Australia’s river systems are defined less by volume and more by catchment size, ecological importance, and their role in sustaining both ancient ecosystems and modern societies.

Murray–Darling Basin

The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s most iconic and important river system—a sprawling inland network that drains nearly one-seventh of the continent. Stretching from the lush foothills of Queensland’s Great Dividing Range through the farmlands of New South Wales and Victoria, and finally to the dry inland plains of South Australia, it is both a lifeline and a landscape of struggle.

At its heart are the Murray and Darling Rivers—long, winding arteries that gather the flow from countless tributaries across the east. The Murray River, Australia’s longest, rises in the snowy peaks of the Australian Alps and carves its way westward for over 2,500 kilometers before spilling into the Southern Ocean near Lake Alexandrina. It’s joined by the Murrumbidgee and Lachlan Rivers, which wind through wheat fields and irrigation canals, sustaining vast agricultural zones.

Lake Eyre Basin

Vast, remote, and mystifying, the Lake Eyre Basin is one of the world’s largest internal drainage systems—a colossal inland catchment where rivers flow not toward the sea, but into the heart of Australia. Spanning over 1.2 million square kilometers, this basin encompasses parts of Queensland, South Australia, the Northern Territory, and New South Wales.

Here, the rivers are ephemeral wanderers, only springing to life after rare inland rains. Cooper Creek, Diamantina River, and the Georgina River are its primary lifelines. Most of the time, they appear as dry channels etched into the earth, but when the rains come—especially during La Niña years—they swell and transform the landscape. These rivers may meander for hundreds of kilometers, breathing life into arid plains, swelling the wetlands, and sometimes, in truly exceptional years, reaching Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre, the great salt lake that sits like a mirror to the sky.

The Lake Eyre Basin is a stronghold of desert biodiversity. Floods bring explosions of life—migratory birds descend by the thousands, frogs awaken from dormancy, and inland fish navigate the rejuvenated creeks. It’s also a cultural landscape, holding deep significance for the Aboriginal nations who have lived with its rhythms for tens of thousands of years.

Unlike other major basins, the Lake Eyre system remains largely unregulated by dams, a rarity that makes it both ecologically precious and incredibly fragile in the face of climate change and increasing development pressures.

Fitzroy River System

In contrast to the dusty silence of the interior, the Fitzroy River in Western Australia pulses with monsoonal energy and cultural meaning. Known as Martuwarra by the Bunuba and other Aboriginal custodians, it flows across the Kimberley region—one of Australia’s last great wildernesses.

The Fitzroy is one of the largest rivers by flow volume in the country, fed by Wet Season rains that drench the north between November and April. During these months, the river bursts across floodplains and gorges, transforming the land into a vibrant, green mosaic. Its tributaries—such as the Margaret River and Leopold River—contribute to a hydrological web that sustains mangroves, monsoon forests, and critical refugia for freshwater species.

The river is home to a number of endemic species, including the elusive freshwater sawfish, and supports thriving populations of barramundi, turtles, and crocodiles. It’s also rich in cultural heritage, with ancient rock art and Dreaming stories etched into the riverbanks and gorge walls.

In recent years, proposals for large-scale irrigation and water diversion projects have raised alarms, prompting calls to protect the Fitzroy as a living ancestral being. A movement to grant it legal personhood, similar to rights given to rivers in New Zealand and South America, is gaining traction—signaling a shift from extraction to guardianship.

Ord River System

Flowing through the rugged red heart of the East Kimberley, the Ord River is a powerful presence in Australia’s tropical north—both a source of life and a symbol of human ambition. Fed by the monsoonal rains of the Wet Season, the river surges through ancient sandstone gorges before slowing into Lake Argyle, one of the largest artificial reservoirs in the Southern Hemisphere.

The Ord River has long been a sacred place for the Miriwoong and Gija peoples, whose knowledge of its seasonal patterns shaped their way of life. But in the 20th century, it became the centerpiece of the Ord River Irrigation Scheme—a massive hydro-engineering project designed to tame the river and transform the desert into farmland. Today, the fertile Ord Valley grows everything from melons and sugarcane to sandalwood and chia, powered by water stored in Lake Argyle and Lake Kununurra.

Yet, the ecological footprint of regulation is clear. While the dam has brought agricultural prosperity, it has also altered natural flood pulses, affecting fish migration, sediment flows, and floodplain health. The lower Ord still carries tremendous biological richness, including freshwater crocodiles, river turtles, and hundreds of bird species, but it now functions as a regulated river, shaped more by policy than by seasonal rhythm.

Coastal Catchments

Beyond the great inland basins, Australia’s coastal catchments form a necklace of shorter, steep-flowing rivers that plunge rapidly from the Great Dividing Range to the sea. Though smaller in length, these rivers are ecologically vibrant and hydrologically crucial—connecting forests, farmlands, cities, and estuaries to the Pacific, Indian, and Southern Oceans.

On the east coast, rivers like the Brisbane, Clarence, and Shoalhaven flow through lush subtropical valleys, past cities and sugarcane fields, into rich estuarine zones. These systems are vulnerable to urban runoff, flooding, and over-extraction, but they also support mangroves, saltmarshes, and important fish nurseries.

Further north, rivers like the Daintree in Queensland flow through ancient rainforests, some of the oldest on Earth. These short but intensely biodiverse rivers descend rapidly from misty highlands, carrying nutrients into coral reef ecosystems like the Great Barrier Reef.

On the western coast, rivers such as the Swan, Gascoyne, and Blackwood traverse dry Mediterranean-climate zones and face mounting pressure from agriculture, salinity, and climate extremes.

Despite their short length, coastal catchments are among Australia’s most densely populated and economically active areas, making the rivers here some of the most contested and carefully managed.

Geological and Ecological Character

Australia’s rivers are ancient storytellers—not just in age, but in temperament. Unlike the youthful rush of Himalayan torrents or the glacier-fed surges of the Rockies, these rivers are slow-moving elders, sculpted by millions of years of weathering, erosion, and evolution. They wind across some of the oldest exposed rock formations on Earth, such as the weather-beaten ranges of the Pilbara or the eroded tablelands of the MacDonnell Ranges, where time feels almost geologic in scale.

Rather than cutting dramatic canyons, many Australian rivers meander gently across low-gradient plains, forming a lattice of braided creeks, anastomosing channels, and wide alluvial floodplains. In drier zones, rivers often vanish into the sand or retreat into ephemeral chains of billabongs—waterholes that remain long after surface flows have ceased. These features are not just relics of past flows; they are lifelines, sustaining uniquely adapted ecosystems.

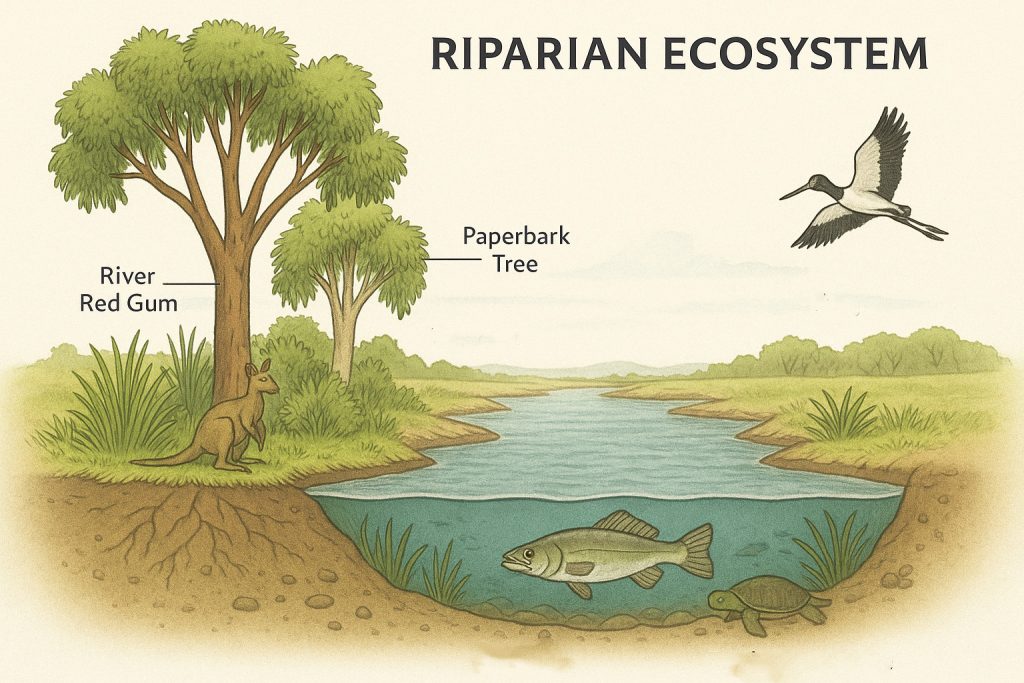

In the tropical north, riparian forests flourish along riverbanks, dominated by paperbark trees, melaleucas, and towering river red gums. These trees rely on regular flooding to replenish groundwater and distribute nutrients. Their gnarled roots bind the soil, while their canopies shelter birds, insects, and possums. Beneath them, the rivers teem with barramundi, saratoga, and freshwater turtles.

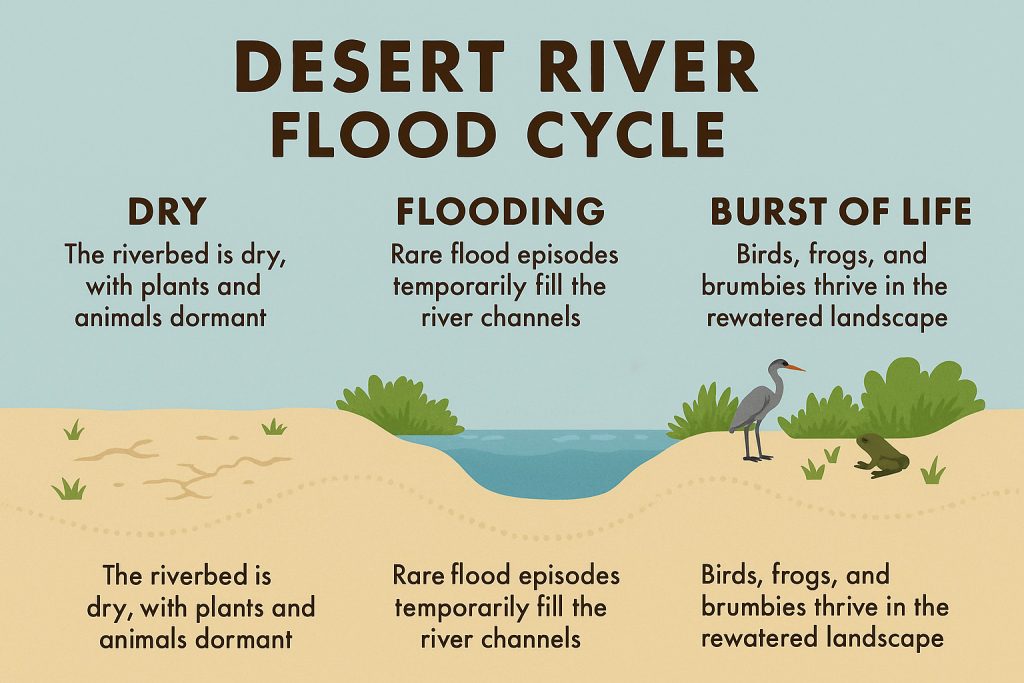

In the interior, where rainfall is rare and unpredictable, the rivers follow a rhythm of boom and bust. Desert rivers, such as those in the Lake Eyre Basin, may remain dry for years, their channels filled with dust and silence. But when the rains do come, they awaken explosively. Water surges across the land, and life follows: frogs erupt from underground burrows, cooper creek catfish begin spawning, and even wild horses (brumbies) gather at temporary waterholes.

These boom-bust cycles fuel the ephemeral wetland ecosystems that appear like mirages and support remarkable biodiversity. Migratory birds like the banded stilt or pelicans arrive in flocks from thousands of kilometers away, taking advantage of the short-lived bounty before the flood retreats and the land dries once again.

Such ecosystems are often rich in endemism—species found nowhere else on Earth—because of the isolated and highly variable nature of these water systems. Yet they are also fragile. Many species rely on the timing and variability of flows rather than consistent water availability. A single dam or mismanaged diversion can unravel the ancient ecological dance that sustains them.

River Morphology in Australia: Where Water Shapes the Land

Australia’s rivers may not boast the constant torrents of wetter continents, but they are master sculptors nonetheless. Over millennia, even intermittent flows have carved out sweeping floodplains, dramatic canyons, tangled estuaries, and broad inland deltas. These river-formed landscapes are living archives of time, climate, and the fragile pulse of water in a dry land.

In the vast Murray–Darling Basin and the remote Channel Country, rivers like Cooper Creek and the Diamantina don’t just flow—they spread, creating wide floodplains laced with braided channels and the iconic billabongs, those tranquil oxbow lakes left behind by wandering streams. When the floods come, these plains awaken in bursts of green, alive with frogs, waterbirds, and golden fields of ephemeral wildflowers.

Where rivers meet the sea, estuaries and deltas unfold—lush and brackish zones where freshwater mingles with salt. The Ord River Delta in Western Australia is particularly striking, forming a rich estuarine system behind tidal sandbars. Similarly, the Hunter River estuary in New South Wales and the Daly River in the Northern Territory are shaped by tide and flow, creating ecosystems that are both ecological sanctuaries and fisheries powerhouses—home to barramundi, mud crabs, and mangrove forests teeming with life.

In the tropical north and the desert interior, rivers have cut deep scars into ancient stone. Katherine Gorge, Glen Helen Gorge, and Barron Gorge are breathtaking examples of river canyons, where water has patiently etched its way through bedrock over eons. These steep-sided gorges, sometimes only accessible during certain flow periods, hold cultural significance for Indigenous communities and offer a rare convergence of geology, ecology, and mythology.

In Australia’s arid heart, one finds unusual forms like alluvial fans and inland deltas—such as those formed by Cooper Creek near Lake Eyre. These sprawling fans of sediment spread out into temporary wetlands and floodout zones, shaping some of the last unregulated dryland river systems left on Earth. Their appearance is sudden, explosive after rain, and vanishing just as quickly—yet they sustain life in the most unlikely places.

Further south and east, the rivers form classic valleys, where flow has sculpted the land into fertile ribbons. The Snowy River Valley, Goulburn Valley, and Derwent Valley are enduring examples. These corridors have long been anchors for agriculture, towns, and transport—productive landscapes where rivers nurture vineyards, orchards, and farmlands, while continuing their slow, ancient work of erosion and deposition.

Australia’s river morphology is a story of contrasts—of abundance and absence, of erosion and renewal. Each bend, gorge, delta, or billabong tells of a moment when water came, carved, and left behind a memory. Understanding these forms is more than a study in geography—it’s a way of listening to the landscape’s oldest voice.

Hydrology: A Dance with Drought

Australia’s rivers are not defined by constancy but by contrast—a hydrological landscape where scarcity is the norm, and abundance arrives in unpredictable bursts. Here, water doesn’t follow a steady rhythm but dances to a chaotic tune composed by climate extremes, tectonic age, and the ever-watchful sky.

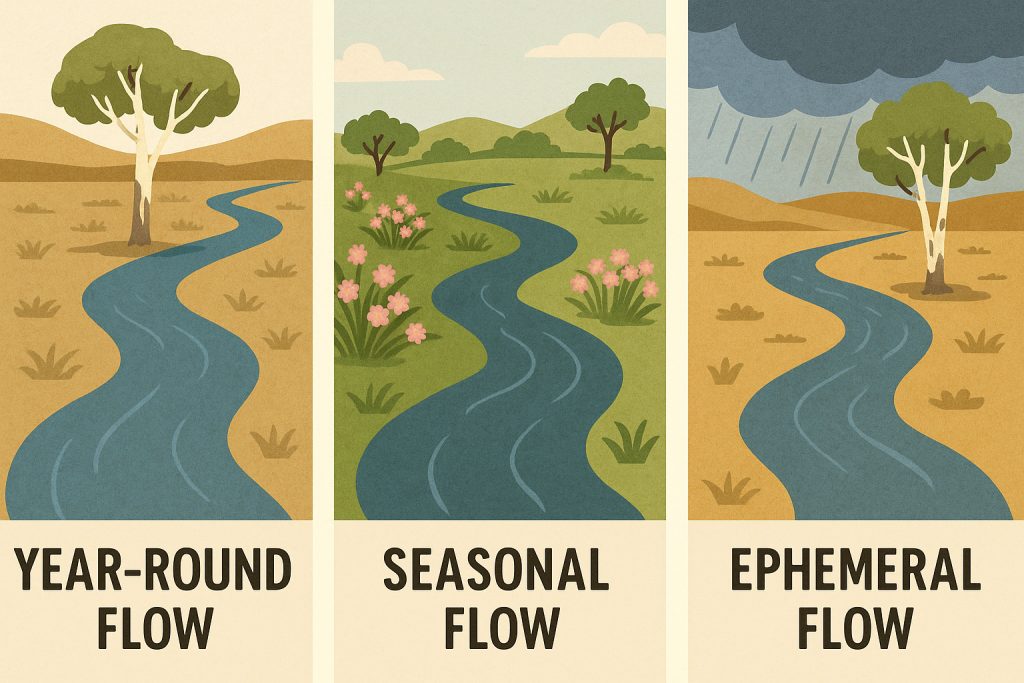

Most rivers in Australia are either intermittent (flowing only part of the year) or ephemeral (flowing only after rain). Only a few rivers—like parts of the Murray, the Snowy, or the Ord—maintain year-round flow, and even these have been reshaped by dams, irrigation channels, and regulation. The hydrological pulse of the continent is driven by large-scale climate phenomena like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Indian Ocean Dipole, which bring either months of searing drought or sudden, torrential rains.

🏜️ Low Runoff and High Losses

Australia has one of the lowest runoff coefficients in the world. Despite some regions receiving heavy rainfall, much of it seeps into the ground, is absorbed by thirsty soils, or evaporates before reaching a stream. In dry inland zones, less than 5% of rain becomes river water.

Even when rivers flood, the water is often fleeting. Vast wetlands such as those in the Channel Country or the Macquarie Marshes bloom spectacularly after a downpour—attracting birds and bursting with life—only to evaporate within weeks, leaving behind cracked mud and memory.

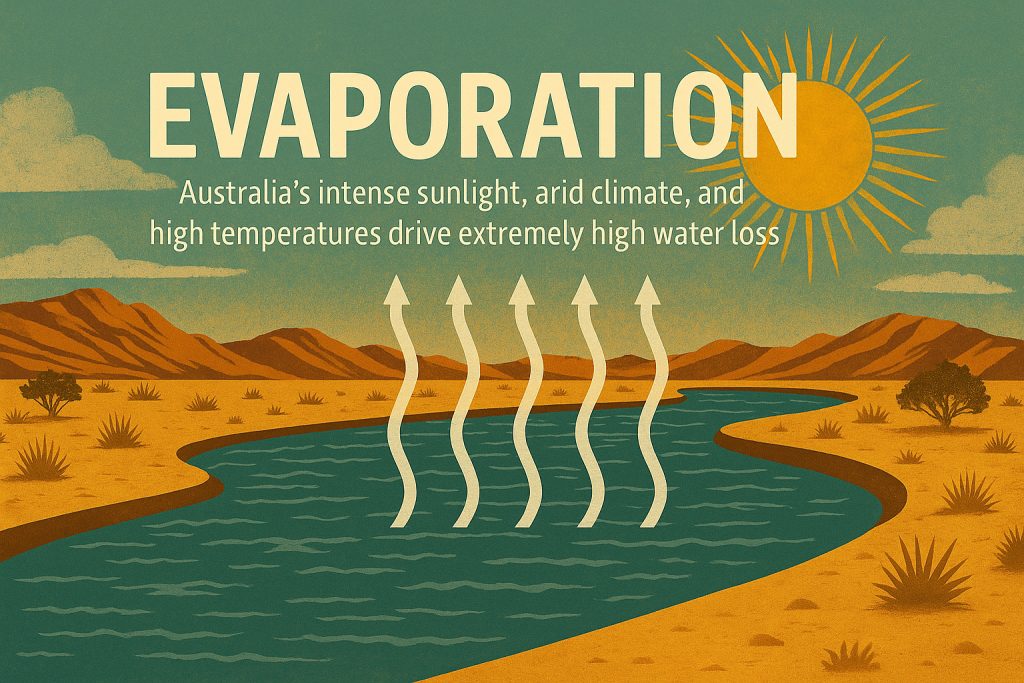

The Thirsty Sky: Evaporation Dominates

Australia’s intense sunlight, arid climate, and high temperatures result in some of the highest evaporation rates on Earth. Water bodies lose more to the air than they give to the sea. It is a land where rivers must not only overcome gravity, but also outpace the sun.

Groundwater: The Hidden Engine

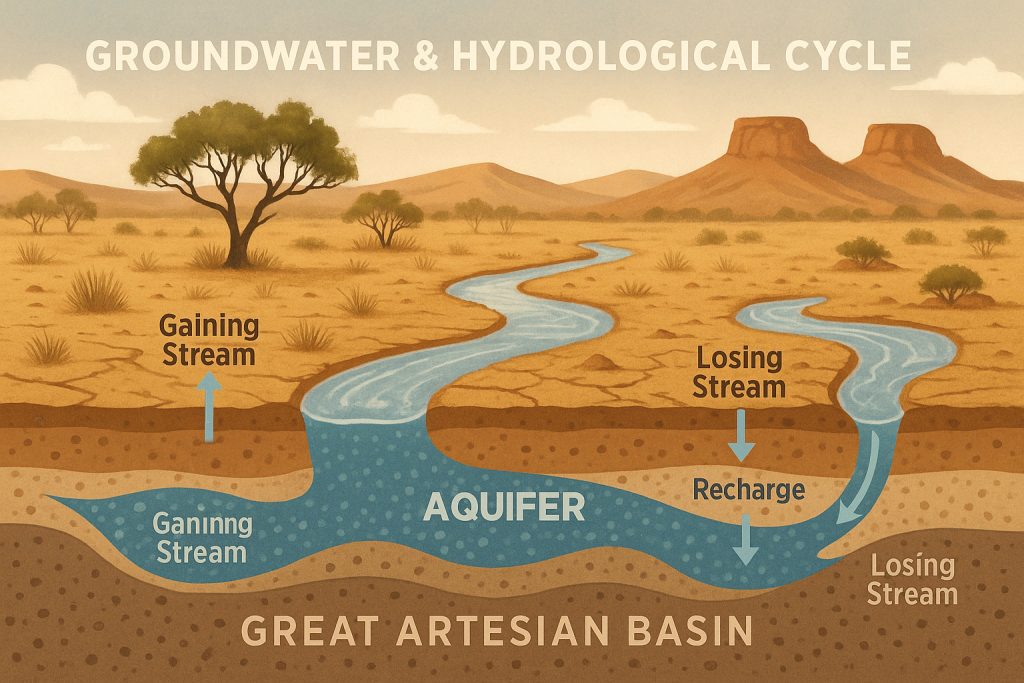

In this parched landscape, groundwater is a silent partner in the hydrological cycle. Many rivers are gaining streams (fed by aquifers) in some stretches, and losing streams (recharging aquifers) in others. This complex interaction sustains dry-season flows in places like the Finke River or Victoria River, and recharges the mighty Great Artesian Basin—one of the largest confined aquifers in the world.

This deep and ancient store of water, pressurized under layers of sandstone, has been tapped for agriculture, towns, and mining, but remains vital for outback springs, sustaining isolated pockets of biodiversity where life clings on in the desert.

Reverse Hydrology: Rivers Rewritten

Nowhere is the modern paradox more clear than in the Murray River, once a meandering giant that carved its way to the Southern Ocean under its own force. Today, its flow is so altered by dams and irrigation that water is often pumped “uphill”, against gravity, to feed thirsty crops in distant fields—a surreal twist known as reverse hydrology. In some stretches, the river flows backward, not because of natural forces, but due to human control.

Australia’s rivers do not simply flow. They vanish, reappear, dive underground, and defy gravity. Understanding their hydrology is not just about measuring rainfall or gauging flow—it’s about reading a land that speaks in droughts, listens in floods, and teaches patience through extremes.

Ecological Richness & Fragility

Australia’s rivers may be dry more often than they are wet—but when they flow, they unleash worlds of life. These ancient waterways, even in their most modest trickles, are lifelines for some of the continent’s most remarkable and unusual creatures. From highland creeks to monsoon-fed wetlands, they form a fragile web of biodiversity found nowhere else on Earth.

Murray Cod: Guardian of the Inland Rivers

In the winding arms of the Murray–Darling Basin, swims the Murray cod—the largest freshwater fish on the continent and one of the oldest native species. This apex predator, steeped in Aboriginal legend, once grew over a meter long and weighed more than 100 kilograms.

Its survival is tied intimately to the health of slow-moving, tree-lined rivers, where submerged logs and overhanging branches provide shelter for both cod and their prey. But dams, sedimentation, and altered flows have reduced their range, and today, these giants are listed as vulnerable, a shadow of their former abundance.

Barramundi: From Ocean to Outback

In the tropical north, barramundi—a fish revered by anglers and Aboriginal communities alike—undertakes great journeys. Born in coastal estuaries, they migrate upstream to freshwater billabongs and floodplains, growing fat and powerful before returning to the sea to spawn. Their life cycle depends on the seasonal pulse of wet and dry, and without monsoonal floods to open passageways, entire populations can falter. Yet where the floodwaters reach, barramundi flourish.

Platypus and Rakali: Ghosts of the Water’s Edge

In the shadowy eddies of rivers and creeks, the platypus plies its ancient trade. This egg-laying mammal, with its duck-like bill and electro-sensing snout, is a global oddity and a national icon. Shy and nocturnal, it vanishes at the slightest disturbance. Alongside it lives the lesser-known but equally fascinating rakali, or Australian water rat, with webbed feet and a luxurious fur coat. Both are sensitive to pollution, bank erosion, and reduced flow. Where waters are clean and quiet, they thrive. Where flows are broken or banks hard-engineered, they disappear.

Floodplains: Avian Highways and Nurseries

Rivers like Cooper Creek, Georgina, and the Macquarie Marshes are dry for years at a time—but when the rain falls far upstream and the flood spreads across the plains, these places become sanctuaries for migratory birds. Flocks of pelicans, banded stilts, herons, and ibises descend from across the continent, sometimes from as far away as New Guinea or East Asia, to breed, feed, and replenish.

Entire colonies emerge in days: nests, chicks, and a cacophony of life. But if the flood doesn’t arrive—or arrives at the wrong time—these natural events may not occur for years. That delicate reliance on irregularity makes Australia’s river ecosystems among the most sensitive to climate change.

Northern Wetlands: Crocodiles and Swarming Life

Further north, in the wet-dry tropics, rivers like the Alligator, Roper, and Daly nourish vast wetlands teeming with life during the monsoon. As rains fall and rivers burst their banks, crocodiles patrol the billabongs, jabirus (Australia’s only stork) wade through waterlogged grasses, and clouds of dragonflies shimmer in the humid air. These seasonal ecosystems are rich but short-lived, and their timing is everything.

Australia’s rivers are not constant—but that’s their magic. Life here is adapted to pulse, to pause, and to wait. But as the climate warms, flows falter, and human pressures intensify, the finely tuned ecological balance that governs these systems begins to strain. To protect Australia’s rivers is to protect a symphony of life—strange, rare, and utterly irreplaceable.

Threats to Australia’s Rivers

Australia’s rivers are some of the most unique and ecologically rich waterways in the world—but they are also among the most vulnerable. Once allowed to flood, wander, and dry in ancient rhythm, many of these rivers now face a multitude of modern pressures that threaten their very existence. From concrete barriers to climate chaos, here’s how Australia’s lifeblood is being choked.

Regulation and Dams: When Rivers Are Tamed

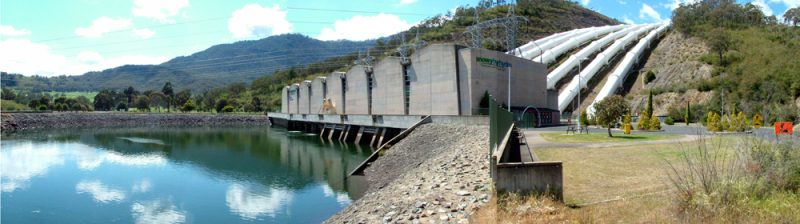

Once wild and unpredictable, many Australian rivers are now regulated by dams, weirs, and diversion channels. Projects like the Snowy Mountains Hydro Scheme—once celebrated as engineering marvels—have diverted water from the Snowy River into the Murray River, fundamentally changing both. Similarly, the Menindee Lakes Scheme has altered the natural pulse of the Darling River system.

By flattening out flow variability, dams interrupt seasonal floods that are critical for triggering fish spawning, recharging wetlands, and refreshing billabongs. Without these natural pulses, native fish fail to breed, wetlands shrink, and floodplain forests begin to die. What was once a dynamic, breathing system becomes a trickle in a concrete straitjacket.

Discover the negative effects of dams on rivers.

Overextraction for Agriculture: Thirsty Crops, Thirstless Rivers

No threat looms larger over Australia’s rivers than the thirst of agriculture. The Murray–Darling Basin, in particular, has become a battleground of water politics and profit. Huge volumes are extracted to irrigate water-hungry crops like cotton and rice, often in arid regions where such farming was never sustainable.

This overuse has led to devastating fish kills—such as the 2019 tragedy in Menindee, where millions of fish, including endangered Murray cod, floated belly-up in oxygen-starved waters. Overuse also fuels blue-green algal blooms, fed by excess nutrients, and creates salinity intrusion—where salt rises to the surface, poisoning soil, crops, and river ecosystems alike.

Climate Change: Turning Drought into Disaster

Australia has always been a land of climate extremes, but climate change is amplifying the volatility. Rainfall patterns are shifting, becoming less predictable and more intense. In inland basins, where flow depends on episodic storms, rivers are drying up faster and staying dry longer.

Hotter temperatures increase evaporation rates, draining wetlands before wildlife can complete life cycles. Bushfires, now more frequent and intense, burn through catchments and forests, leaving ash, sediment, and toxins to wash into rivers during storms—clogging habitats, killing fish, and altering water chemistry.

Meanwhile, rising sea levels are pushing saltwater farther up estuaries, threatening the delicate balance of coastal river ecosystems.

Invasive Species: Unwanted Guests in Fragile Waters

With altered flow and weakened ecosystems, native species have become vulnerable to invasive aquatic life—many of which were introduced either deliberately (for fishing) or accidentally.

The most notorious of these is the common carp, which now dominates many inland waterways. Carp muddle the water as they feed, uprooting plants and stirring up sediment, leading to cloudy, oxygen-poor rivers where native fish struggle to survive. Similarly, mosquitofish, introduced for mosquito control, have outcompeted and preyed upon small native species.

These invaders thrive in regulated, degraded systems, making their spread both a symptom and a cause of river decline.

The Future: Rewilding the Rivers?

There’s hope in rewilding. Projects like the Murray–Darling Basin Plan, Aboriginal water rights movements, and river restoration efforts in Northern Australia are slowly shifting priorities.

And in 2021, the Martuwarra Fitzroy River was proposed to be granted legal personhood, echoing a global shift to view rivers not just as resources, but as living systems with rights.

Conclusion

Australia’s rivers are more than waterways—they are threads of life in a dry land, bearers of stories, sacred paths, and survival corridors. They flow through dreaming tracks, past red cliffs and gum trees, bearing witness to both ancient life and modern struggle.

Protecting them isn’t just about water—it’s about honoring the rhythms of a land that has always known how to survive, if only we listen.