Negative Impacts of River Regulation

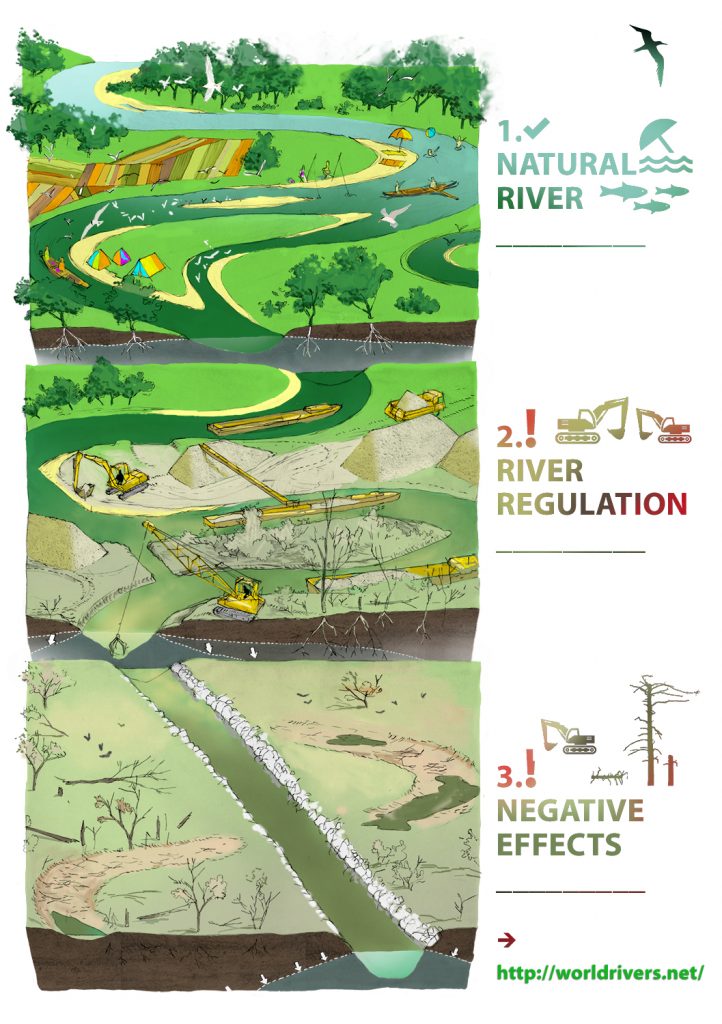

River regulation alters natural flow for flood control, navigation, or irrigation—but often causes severe ecological and geomorphic harm.

Since ancient times, people have settled near rivers—drawn by water, fertile land, and trade routes. But living close came at a cost: erosion and devastating floods. To protect themselves and harness rivers for navigation, irrigation, and development, societies began regulating streams—straightening their paths and lining them with stone and concrete. From early civilizations to modern engineering, river regulation has become widespread. Yet over time, it has revealed drastic, often damaging consequences for the environment and the people themselves.

What Is River Regulation?

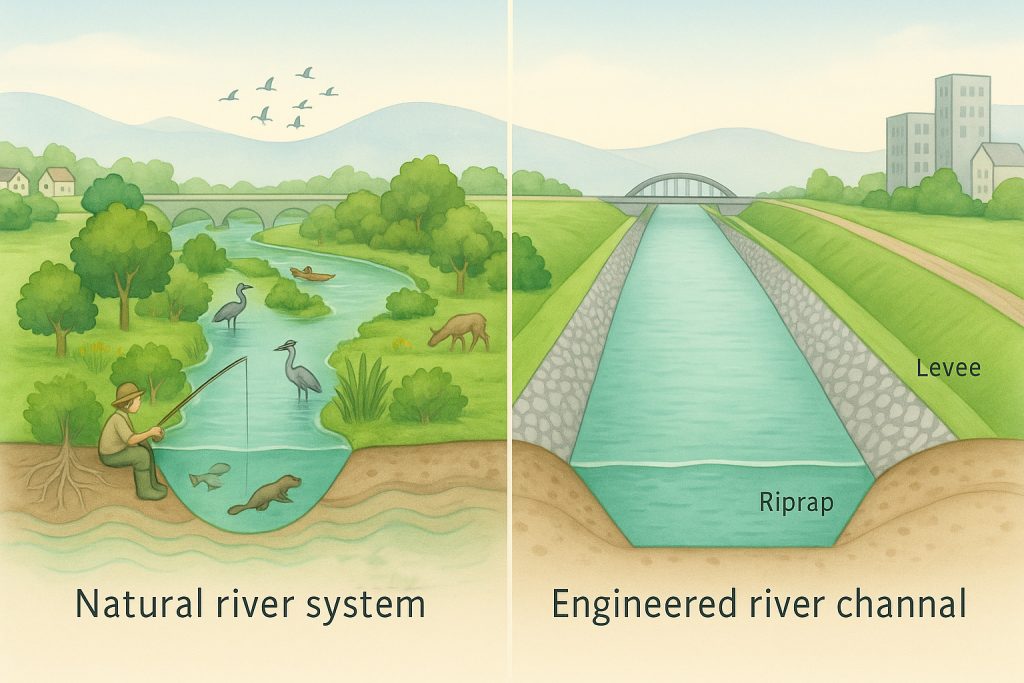

River regulation refers to the engineering and alteration of natural river systems to serve human needs. In a broader sense, it involves modifying the river’s entire dynamic—reshaping its flow, disrupting natural processes, and often converting floodplains into urban or industrial zones. The goal is typically to control floods, prevent erosion, enable navigation, or support irrigation.

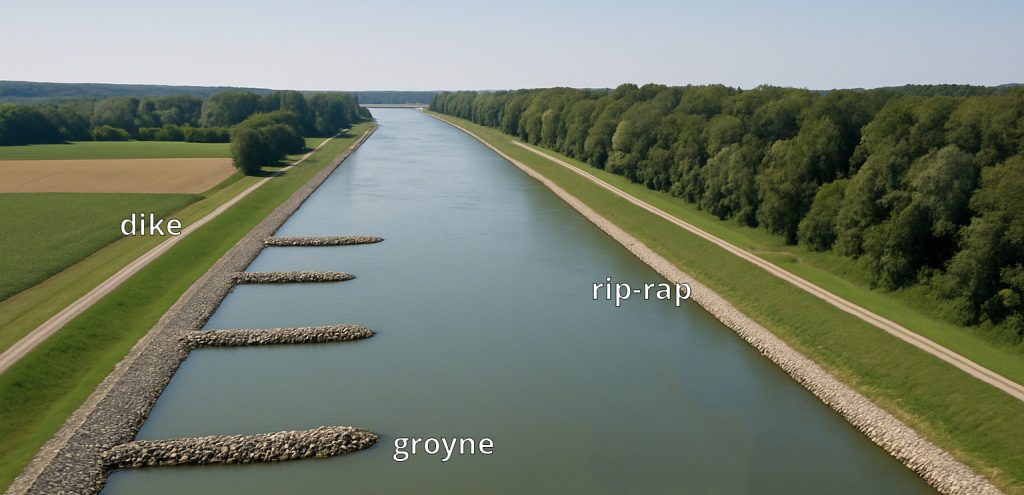

To regulate a river, its course is often straightened and confined. This is achieved by reinforcing the banks—commonly using embankments made of stone, concrete, or modern materials—to stop lateral erosion. One widely used method is riprap, a layer of durable rocks (usually granite or limestone) or concrete debris placed along shorelines and riverbanks to resist water or ice erosion.

Another key method is the construction of river groynes—also called spur dykes, wing dykes, or wing dams. These structures are built perpendicular to the riverbanks to redirect the current away from undesired paths. By doing so, they help prevent natural meandering and are primarily used on large rivers to improve navigation.

To make boat transport faster and more efficient, rivers are often straightened—a process that involves cutting off natural meanders. A prime example is the Mississippi River, which has been significantly shortened over time through engineering efforts by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and others.

For flood protection, structures like dikes, levees, and dams are built along riverbanks. These elevated earthworks are designed to keep floodwaters contained—but when placed too close to the river, they drastically reduce the floodplain’s natural water storage capacity.

Ripraps, groynes, and dikes form the basic toolkit of river regulation, but many other techniques exist, including diversion canals, floodgates, and spillways.

In effect, a once dynamic, meandering lowland river—intertwined with a wide, fertile floodplain—is transformed into a static, straight channel lined with stone or concrete. The floodplain is often disconnected or fully urbanized, leaving the river stripped of its natural processes and ecological vitality.

The Negative Consequences of River Regulation

Forcing a flowing river into a rigid, artificial channel might seem like a practical solution—after all, it promises flood protection, better navigation, and land development. But beneath the surface lies a cascade of unintended consequences. River regulation disrupts natural systems in profound ways, affecting not just the environment but also the people who depend on it.

Loss of Biodiversity and Natural Habitats

One of the most immediate and visible effects of river regulation is the loss of biodiversity. A natural river meanders freely through its floodplain, creating a rich mosaic of landscapes: gravel bars, wetlands, side channels, riparian forests. These diverse habitats host an abundance of life—fish, amphibians, birds, insects, and plants that all depend on the river’s natural rhythm.

When a river is straightened and lined with concrete or stone, this complexity disappears. What remains is a uniform canal, devoid of variation. The intricate web of life once supported by natural features simply vanishes. It’s a dramatic simplification of the landscape—and it’s no surprise that when habitat diversity is lost, species disappear with it.

Riverbed Degradation: A Deepening Problem

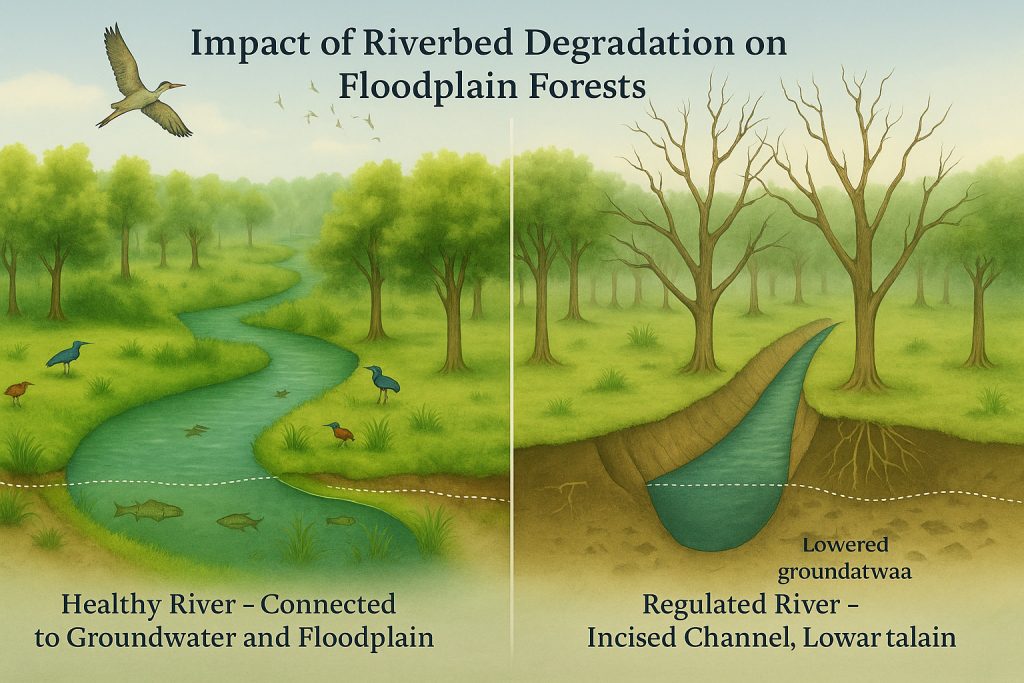

Once a river’s banks are armored with stone or cement, water can no longer erode sideways. Instead, it turns downward, focusing its energy on the bed of the river. This leads to a process called riverbed degradation, where the channel carves itself deeper and deeper into the landscape.

As the bed sinks, the river begins to lose its connection with its surroundings. Side arms dry up. The floodplain is left stranded. High waters that once spread out into wetlands are now confined to a narrow, deep channel, increasing the speed and force of flow. What was once a gentle, dynamic system becomes a hardened chute.

This vertical erosion is so widespread today that many river revitalization projects are now trying to reverse it—reconnecting rivers with their floodplains and raising beds to restore some of the lost balance.

One of the most dramatic side effects of riverbed degradation is the drop in the groundwater table. As the river cuts lower into the landscape, the surrounding underground water follows. Trees that once thrived along the banks begin to suffer. Their roots can no longer reach the receding moisture. Crops dry out. Forests lose their vitality. Wetlands disappear.

This hidden shift in the water balance can create drought-like conditions even in areas with a nearby river. Ironically, instead of helping with water supply, a regulated river may increase the risk of drought across its basin.

Disruption of Natural Fertility

Historically, rivers brought life to floodplains by depositing nutrient-rich sediments during seasonal floods. These natural fertilizers enriched the soil, supporting both wild vegetation and agriculture. But once levees and dikes are installed, rivers can no longer overflow into the land. The supply of fresh sediment stops.

As a result, farmers must now compensate with artificial fertilizers, which not only come at a cost but also pollute the environment. Excess nutrients from farms run off into the water, leading to problems like algae blooms and dead zones downstream. What was once a free service provided by nature becomes a burden we must manage.

The Illusion of Flood Protection

A major justification for regulating rivers is flood control, yet this often backfires. By walling in the river with levees and narrowing its channel, the water has nowhere to go during high flow events. Instead of safely spilling into the floodplain, it stays trapped in the channel—until the pressure becomes too great.

When heavy rainfall hits upstream, the embanked river quickly fills to capacity. With no room to expand, the water surges over or through the levees, sometimes with catastrophic force. Entire settlements that believed they were protected may find themselves underwater.

Rather than preventing floods, river regulation may delay them—and make them far more destructive when they finally come.

Loss of Ecosystem Services

A healthy, natural river does much more than carry water. It filters pollutants, stores carbon in wetlands, cools the local climate, and supports recreation, tourism, and local economies. These are known as ecosystem services, and they are worth billions globally.

Explore ecosystem services in greater depth to gain a better understanding.

When a river is reduced to a sterile, engineered channel, these services vanish. Water quality declines. Wildlife disappears. Tourism fades. The benefits once freely provided by nature must now be replaced by expensive infrastructure and technology.

The more we regulate rivers, the more we find ourselves paying to restore what we’ve lost.

The Value of Floodplains and Natural Retention

Floodplains are nature’s flood buffers. When preserved, they allow rivers to spread out during high flows, reducing the risk of catastrophic flooding downstream. Floodplain forests and wetlands are not only able to survive long-term inundation—they’re built for it. These ecosystems are resilient, adapting to both flood and drought, erosion and deposition.

Yet, we often fixate on erosion as a threat, forgetting the other side of the story: sediment deposition. Without this process, rivers would endlessly widen their beds. But that’s not what we observe. In a healthy, meandering river system with space to breathe, erosion on one bank is naturally balanced by sediment buildup on the other.

Over time, this process shapes new habitats—gravel bars, sandbanks, and islands—often restored and teeming with life in just a few years.

Rivers Are Dynamic—And So Is Nature

In Europe, willows and poplars thrive in these shifting environments, growing more than a meter in a single year. In South America, fast-growing trees like Cecropias quickly reclaim young floodplain land. This rapid recovery highlights the regenerative power of natural rivers.

Yes, erosion may take a strip of land today—but tomorrow, sediment will build new life elsewhere along the flow. A river that is free to meander within its natural boundaries creates its own balance.

Protection Through Space, Not Restriction

Naturally, we must protect human lives and infrastructure. But the solution is not tighter control. It’s giving rivers more room—space to flood, to erode, to meander, and to heal.

Even in urban and semi-urban areas, we can redesign our approach. Instead of channeling rivers into narrow, concrete corridors, we can create buffer zones, green corridors, and multi-functional floodplains that both serve people and restore nature.

Delve deeper into flood prevention to enhance your understanding

This is where river restoration plays a key role. By reconnecting rivers with their floodplains, removing obsolete levees, and reviving wetlands, we not only reduce flood risk—we revive entire ecosystems, improve water quality, and support biodiversity.

Learn how a New understanding of the rivers sees the vital role of the preserved floodplain.

A Smarter Future with Wiser Rivers

The future of water management isn’t about domination—it’s about coexistence. Preserving and restoring floodplains isn’t just good for the environment—it’s smart, long-term thinking that protects our towns, our agriculture, and our climate.

The river doesn’t need to be controlled. It needs to be understood—and given room to move.

Conclusion: Taming Rivers Comes at a Cost

At first glance, river regulation seems to offer solutions. But as we dig deeper, it becomes clear that controlling rivers comes with severe consequences. From ecological collapse to economic burdens, the transformation of dynamic waterways into engineered ditches creates far more problems than it solves.

We’ve broken the natural connections between rivers, landscapes, and communities. If we want to protect the environment and ourselves, we must rethink how we interact with rivers. Restoring their natural flows, reconnecting them to their floodplains, and respecting their power are no longer idealistic goals—they are necessary for our future.

To truly coexist with rivers, we must shift our perspective. A new understanding of river systems recognizes the vital role of floodplains—not as empty land waiting to be developed, but as dynamic, life-sustaining landscapes that serve essential ecological and hydrological functions.