River Sidearms and Deadarms: Nature’s Quiet Branches

Discover the hidden life of river sidearms and deadarms—vital, quiet channels that shape ecosystems, store history, and reveal nature’s resilience.

In the grand anatomy of a river, not all channels roar. Some whisper. Winding away from the main current, river sidearms and deadarms—also known as sideranches and deadbranches—are the silent tributaries of the river world. Though often overlooked, these features are ecological treasure troves and key indicators of a river’s health and history.

What Are River Sidearms and Deadarms?

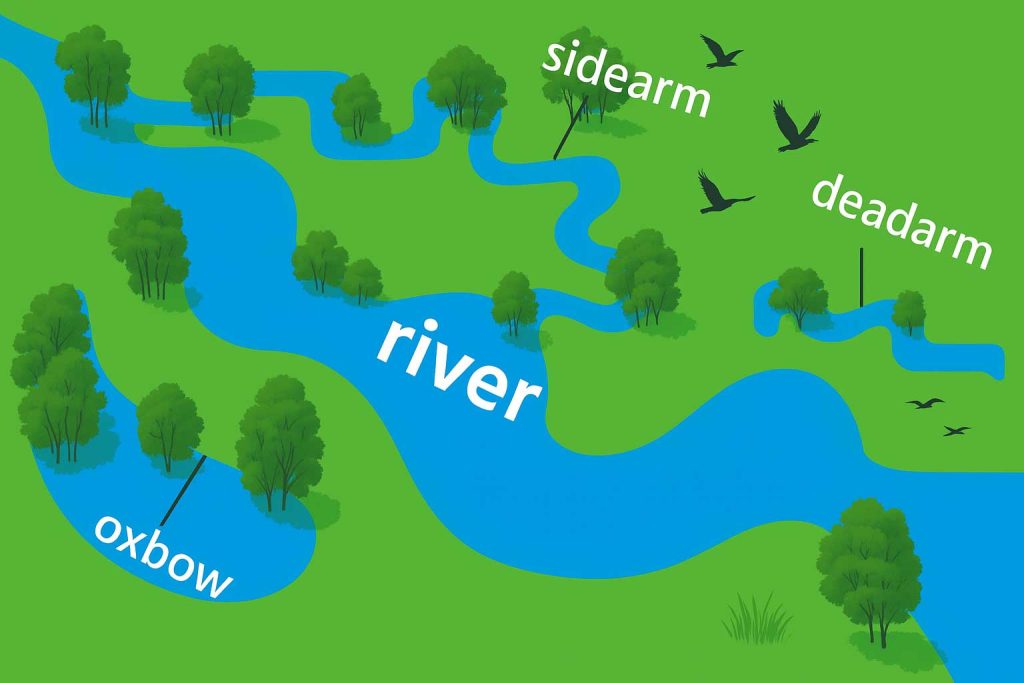

Sidearms are secondary channels that split off from the main river and may rejoin it downstream. These flowing side channels can be permanent or seasonal and are often rich in biodiversity. Sometimes called sideranches, they carry water during floods or high-water periods, and in some cases, even maintain base flow year-round.

In contrast, deadarms (or deadbranches) are abandoned or cut-off river channels—no longer connected to the main flow. These tranquil water bodies often form due to sediment deposition, natural meandering, or human intervention (e.g., levees, dams, channelization).

Over time, a sidearm may become a deadarm if it loses its connection to the main channel. When a dead branch curves in a crescent shape—typically a former river meander—it’s called an oxbow lake. These features usually form when sediment cuts off the meander from the main river, leaving behind a still, isolated water body. Oxbow lakes are classic examples of river evolution and are often rich in biodiversity.

River Sidearms and Deadarms – Hotspots of Biodiversity

Sidearms are among the most vital habitats in lowland river systems. As dynamic offshoots of the main channel, they weave through the floodplain and eventually reconnect with the river, creating a mosaic of flowing and semi-stagnant water. Their very presence is a sign of a living, untamed river—constantly shifting, shaping, and adapting.

Over time, when a sidearm becomes cut off from the main flow, it transforms into a deadarm. These disconnected channels often take on a curved, crescent shape—a remnant of the river’s past meanders—becoming what is known as an oxbow lake. These calm, isolated waters are born from the river’s natural evolution and are particularly abundant along wide, meandering lowland rivers.

Far from lifeless, deadarms are ecological havens. Together with active sidearms, they support an extraordinary range of life—offering refuge for fish, nesting grounds for birds, breeding zones for amphibians, and lush growth for aquatic plants. Over decades, as rivers abandon old paths and carve new ones, they leave behind a rich network of side and dead branches that boost biodiversity and sustain the health of the riverine landscape.

Where Rivers Breathe: Life in the Calm Waters of Sidearms

The current slows in the sidearms, whispering instead of roaring. These channels are shallower than the main river course and often filled with sediment, forming a gentle interface between land and water. Here, forests touch floodplains, and ecosystems intertwine—deer wander down from the woods to drink, while herons and egrets stalk through the reeds.

The lush vegetation and tranquil waters offer ideal conditions for fish, especially during the breeding season. In Europe, Carp (Cyprinus carpio) and other species move into sidearms and deadarms in May and June to spawn, attaching their eggs to submerged plants or gravel beds. These calmer waters protect their eggs from strong currents and lurking predators of the main river.

Once hatched, the fish fry remain in these quiet sanctuaries, feeding and growing until they are strong enough to rejoin the river’s flow. During this vulnerable phase, they are a key food source for birds such as the brilliant kingfisher (Alcedo atthis)—a shimmering flash of blue over the still waters.

From Water to Wetland: The Living Evolution of a Deadarm

A deadarm is not a dead zone—it is, in truth, a living wetland, full of growth, light, and silent transformation. Along its shallow margins, reeds (Phragmites australis), bulrushes (Typha latifolia), and sedges (Carex spp.) rise from the mud, forming a green fringe between land and water. Broad water lilies (Nymphaea alba) float lazily on the surface, while beneath them, Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) grows in dense, feathery underwater forests.

These stagnant waters are bathed in light, allowing sunshine to penetrate the entire water column. Photosynthesis flourishes. Aquatic plants and algae bloom, creating a pulse of life that sustains insects, amphibians, and birds. When these organisms die, their remains sink, enriching the bottom with organic mud.

This is eutrophication in its natural form—not pollution, but the graceful aging of a water body. Over time, the deadarm becomes increasingly shallow, filled with silt and life’s detritus. Eventually, willows, alders, and more sedges take root in the shallows, reclaiming water inch by inch. The wetland begins to transform again—toward a marsh, a meadow, and eventually, perhaps, forest. It is a slow-motion metamorphosis of water into land.

Oxbow Lakes: Biodiversity Sanctuaries of Still Water

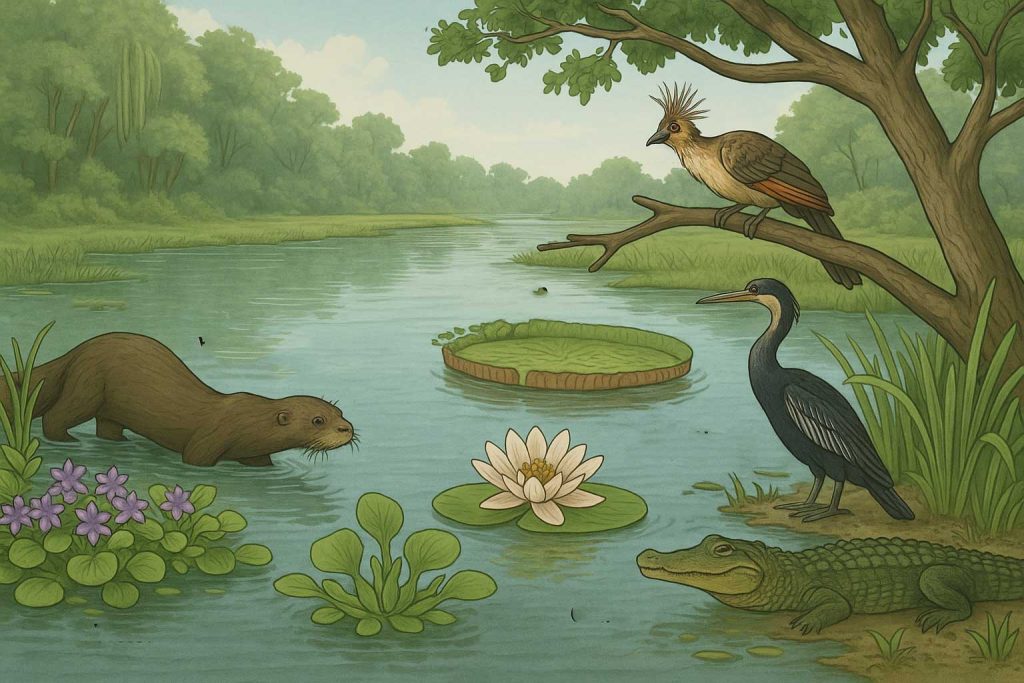

In the heart of Latin America’s great river basins, oxbow lakes shimmer like fragments of the past—vast, crescent-shaped remnants of ancient meanders. Scattered along the floodplains on both sides of rivers like the Amazon, Orinoco, and Paraná, these still waters are biodiversity hotspots of the Neotropics.

Here, giant otters (Pteronura brasiliensis) slide through the lilies, their powerful bodies slicing the surface with ease. Caimans bask motionless on muddy banks, and anhingas (Anhinga anhinga) perch with wings outstretched, drying after a dive. In the overhanging branches, the peculiar hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin)—a prehistoric-looking bird with blue skin around its eyes and a spiky crest—clumsily climbs and croaks, its chicks even using claws on their wings.

The calm waters nourish explosive plant growth. Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) forms floating mats that drift lazily with the breeze, while the majestic Victoria amazonica spreads its giant leaves like green plates across the lake’s surface—each capable of holding a small child.

These lakes are crucial refuges for wildlife during dry seasons and serve as nurseries for countless fish and amphibians, part of a rich mosaic of floodplain ecosystems. In their silence, the oxbow lakes echo the story of a river’s eternal transformation—and the life that springs from it.

After many years, a forest returns, and it remains until the river once again migrates across its floodplain, driven by its dynamics, invading the forested area and starting the evolutionary process again.