The Negative Effects of Dams on Rivers

Discover the negative effects of dams on rivers—from disrupted ecosystems and blocked fish migrations to sediment loss and vanishing wetlands.

Dams are often hailed as a source of cheap, green energy—but the reality is far more complex, and far less sustainable. They have many negative effects of dams on rivers.

While hydropower dams—distinct from dams built solely for flood control or irrigation—have indeed played a pivotal role in global electrification, their darker side is frequently overlooked. From the thundering marvels like Niagara Falls, where Nikola Tesla once helped harness a fourth of America’s electricity, to countless smaller installations worldwide, dams have symbolized human mastery over rivers. They’ve brought electricity to remote regions, aided agriculture, and even provided some flood protection.

But behind the promise of “clean energy” lies a cascade of environmental consequences. The disruption of natural river flow, loss of biodiversity, sediment starvation, and the displacement of communities are just a few of the costs rarely mentioned in public discourse. In truth, the negative effects of dams on rivers are profound, widespread, and often irreversible.

The Myth of Multifunctionality: How Dams Are Oversold

Dams are frequently promoted as multifunctional marvels—offering energy, flood control, irrigation, recreation, and even ecological benefits. But this is often more propaganda than fact.

In reality, many of these so-called functions rarely operate as promised. Claims of multifunctionality are often used to disarm opposition and justify projects that serve narrow interests. In promotional materials, dams are made to sound like a win-win for people and nature alike—clean energy, regulated rivers, even wildlife protection. Some investors go so far as to argue that dams improve ecosystems.

Don’t be fooled. These narratives are designed to secure approval and funding, while downplaying the irreversible damage dams often inflict. In some cases, it almost seems as if electricity production is treated as a mere bonus—while the broader ecological cost is swept under the rug.

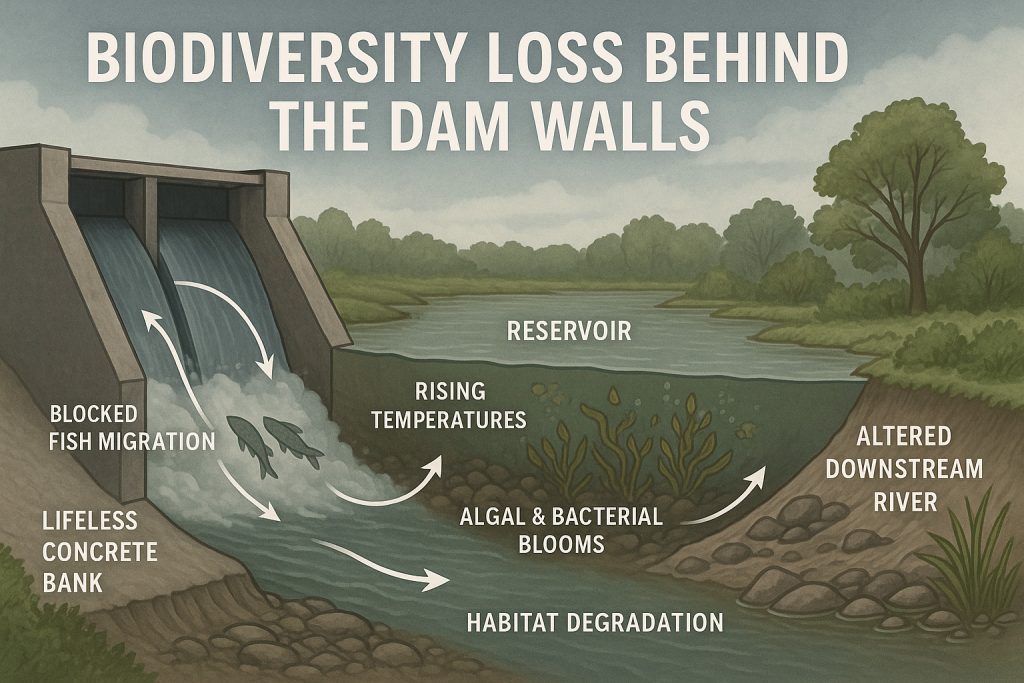

The Silent Collapse: Biodiversity Loss Behind the Dam Walls

When we talk about the impact of dams, the devastating toll on biodiversity often gets overshadowed by technical or economic discussions. Yet, this is one of the most far-reaching and tragic consequences.

Everyone has heard that dams block fish migration—but the story doesn’t stop there. The construction of a dam and its reservoir completely transforms the local ecosystem. Lush, shaded riverbanks are replaced with bare, sterile concrete shores. Vegetation disappears. The cooling canopy vanishes. In its place: stagnant waters, rising temperatures, and the perfect conditions for algal blooms, bacterial outbreaks, and oxygen-starved zones.

Everyone has heard that dams block fish migration—but the story doesn’t stop there. The construction of a dam and its reservoir completely transforms the local ecosystem. Lush, shaded riverbanks are replaced with bare, sterile concrete shores. Vegetation disappears. The cooling canopy vanishes. In its place: stagnant waters, rising temperatures, and the perfect conditions for algal blooms, bacterial outbreaks, and oxygen-starved zones.

The damage goes deeper still. Rivers are naturally dynamic systems, constantly reshaping themselves—meandering, flooding, carving new channels. This ever-changing rhythm creates a mosaic of habitats that support an astonishing range of life.

But with a dam in place, that rhythm stops.

The river becomes static.

It ages prematurely, rushing toward the final stage of habitat succession without ever cycling through the diversity of earlier stages.

In simple terms: entire life cycles vanish, and with them, the species that depended on those stages.

The result?

A sharp and irreversible drop in biodiversity.

💧 Beneath the Surface: Riverbed Degradation and Falling Groundwater

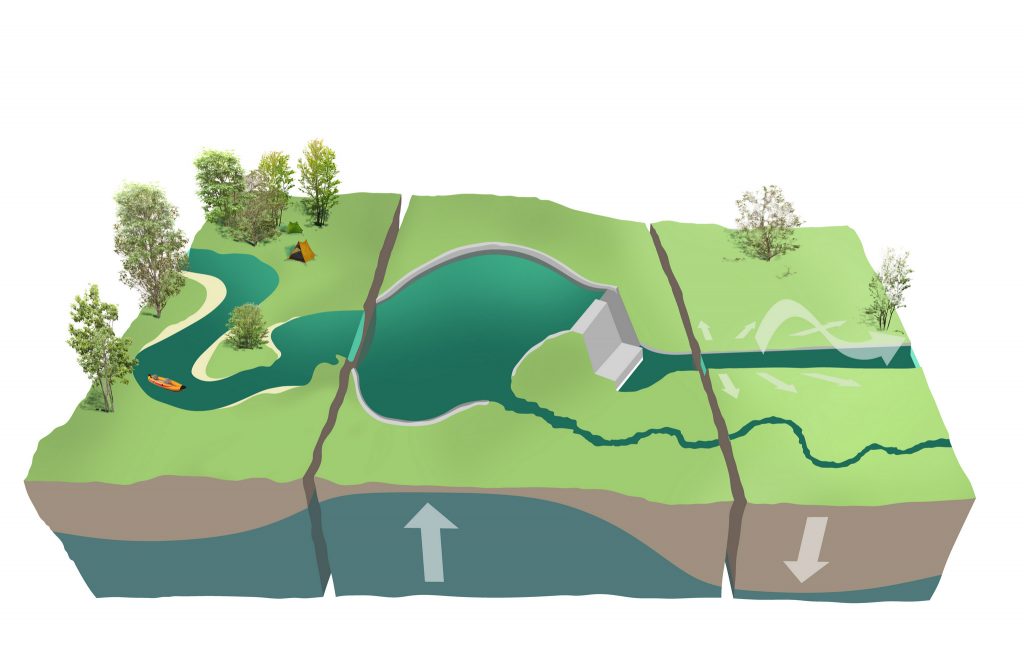

The reach of a dam extends far beyond its towering wall. Its impact ripples dozens of kilometers upstream and downstream, reshaping the very skeleton of a river and everything that depends on it.

One of the most dramatic disturbances is hydropeaking—the artificial pulsing of water releases to match electricity demand. These daily surges and drops, often more than a meter in variation, destabilize habitats, disorient aquatic species, and disrupt natural rhythms that river ecosystems rely on.

But the damage goes deeper—literally. Sediment that would naturally replenish the riverbed gets trapped behind the dam, starving downstream sections. With nothing to rebuild itself, the river begins to cut into its own floor, carving downward through layers of geology. This process is known as riverbed incision.

As the river deepens, it becomes disconnected from its floodplain—if one remains at all. Floodplains are nature’s sponges and biodiversity havens. Without regular overflow, they dry out, and so do the ecosystems and communities that rely on them.

Groundwater suffers too. Rivers and aquifers are connected in a delicate hydrological dance. As the riverbed sinks, the water table drops, leaving forests, wetlands, and crops gasping for moisture. Wells run dry. Springs vanish. Rural livelihoods falter.

In river deltas, the consequences are even more severe. Dams starve these fragile landscapes of sediment. Without fresh deposits, the land sinks, and saltwater pushes inland, poisoning soils and rendering once-fertile farmland useless.

From alpine headwaters to lowland deltas, the degradation is systemic. And all of it—every cut, every drop—is the quiet legacy of a dam upstream.

As the riverbed sinks, so does the surrounding groundwater level. Springs dry up. Wetlands shrink. Agricultural wells run dry.

And the banks? They’re often reinforced with rock or concrete, suppressing natural erosion and further choking the river’s ability to restore itself with fresh sediment. The entire system becomes mechanized, rigid, and ecologically impoverished.

🌊 Dams and Floods: Protection or Peril?

Dams are often portrayed as defensive bulwarks against flooding—but the truth is more nuanced. Paradoxically, they can both mitigate and magnify the risk of floods.

On one hand, dams and reservoirs can indeed hold back small to moderate floods, the kind that refill aquifers and rejuvenate wetlands. These so-called “good floods” soak into the floodplain, where the water undergoes natural purification by plants, bacteria, and soil organisms, recharging underground water reserves in the process.

But here’s the catch: most large dams are powerless against the worst floods—the catastrophic ones. When a reservoir nears its capacity, operators must release huge volumes of water to protect the dam itself. This emergency discharge can create downstream surges akin to tsunamis, wreaking havoc on communities and landscapes that were falsely believed to be protected.

In contrast, natural floodplains are extraordinary in their ability to absorb and buffer extreme flooding. They store vast volumes of water, slowing the flood wave, filtering it, and spreading it safely across the landscape.

A UNDP study in Croatia quantified this value:

the floodplain of the Drava River offers over $5,000 per hectare in flood protection. That’s the amount we’d need to spend on technical defenses to match what nature provides for free.

So while dams may offer a short-term sense of security, true long-term resilience lies in preserving and restoring natural floodplains—the Earth’s original and most effective flood protection system.

🔻 More Negative Effects of Dams on Rivers

Fragmentation of River Continuity

Dams interrupt the natural flow of rivers, slicing them into isolated segments. This fragmentation breaks ecological connections, affecting migratory species (like salmon, sturgeon, and eel) and reducing genetic exchange between populations.

Thermal Pollution

Water released from the bottom of a dam (hypolimnion) is often colder or warmer than the natural flow, depending on the season. This alters downstream temperature regimes, which can kill temperature-sensitive species or disrupt spawning cycles.

Oxygen Depletion (Hypoxia)

Deep, stratified reservoirs may become oxygen-starved at the bottom. When this oxygen-poor water is released, it can suffocate aquatic life downstream.

Blocked Nutrient Transport

Rivers are natural conveyors of nutrients. When sediments and organic matter are trapped behind dams, floodplains and deltas starve, leading to a loss of soil fertility and productivity.

Increased Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Contrary to popular belief, some reservoirs—especially in tropical regions—emit significant amounts of methane and CO₂ from decomposing vegetation and sediments underwater. These emissions can make some dams dirtier than fossil fuels in terms of climate impact.

Salinization of Soils

By altering natural flood cycles and groundwater flow, dams can contribute to soil salinity, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. This harms agriculture and further degrades land.

Erosion of Riverbanks and Coastal Zones

Downstream from the dam, sediment-hungry rivers may erode their banks and even coastlines, worsening land loss in delta regions (e.g., the Nile, Mekong, and Mississippi).

Loss of Cultural and Spiritual Values

Many rivers are sacred or culturally significant. Damming often floods ancient sites, cemeteries, and spiritual places. It can also disrupt cultural practices tied to seasonal flows, fishing, or river festivals.

Seismic Activity and Reservoir-Induced Earthquakes

Large reservoirs can induce seismic events by increasing pressure on fault lines beneath the surface—this is a documented phenomenon known as Reservoir-Induced Seismicity (RIS).

Invasive Species Spread

Stagnant or altered habitats behind dams can become breeding grounds for invasive plants, fish, and insects, which then outcompete or destroy native species.

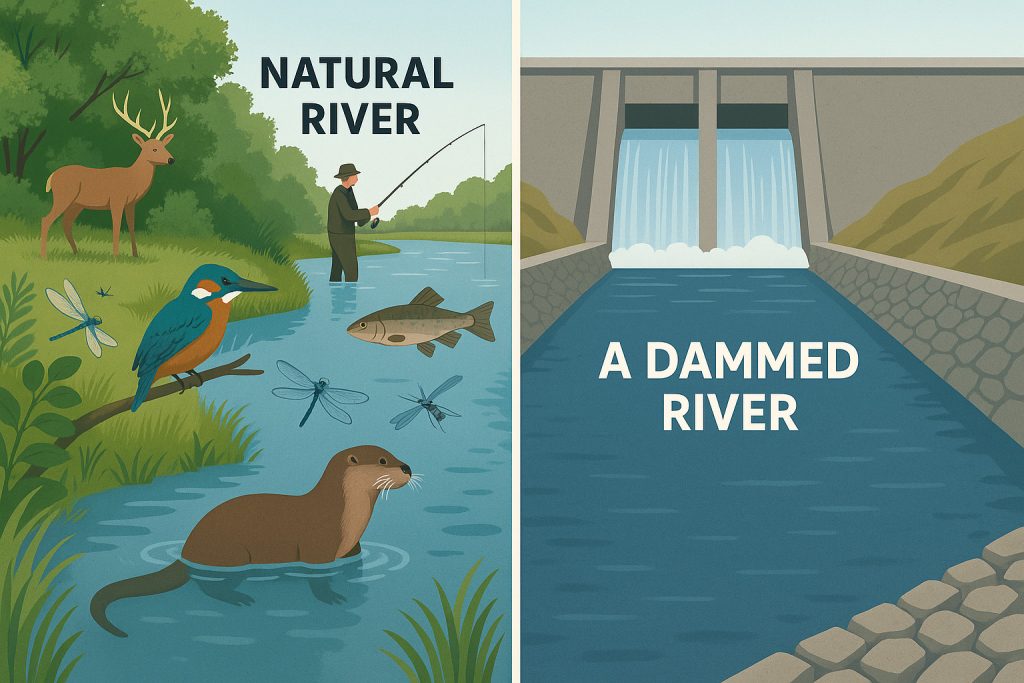

🌿 Loss of Many River Benefits

A river in its natural, free-flowing state offers countless benefits to people—many of which go unnoticed until they’re gone.

It provides clean water, supports fisheries, naturally fertilizes floodplains, replenishes groundwater, and offers protection against floods through its dynamic floodplain. Rivers are also vital for recreation, cultural identity, and mental well-being, offering a sense of place and continuity that no reservoir can replicate.

When a river is dammed, these benefits are diminished or lost entirely. The price we pay is not just ecological—it’s deeply human.

When the River Turns Against Us: The Human Cost of Dams

The story of dams is not only one of ecological disruption—it’s also a deeply human one. Beyond the loss of biodiversity, entire communities bear the brunt of altered riverscapes.

Some impacts are indirect but profound. As already mentioned, sediment starvation, increased flood risk, and riverbed degradation can devastate agriculture—washing away fertile topsoil, drying out fields, and ruining irrigation systems. Crops fail, and livelihoods collapse.

Then there’s the vanishing beauty of rivers once prized for their natural charm. Straightened banks, concrete barriers, and algal blooms replace clear waters, gravel bars, and lush greenery. Tourism suffers—fishing, swimming, kayaking, and ecotourism all decline as rivers lose their life and allure.

Without seasonal flooding, the land is no longer naturally fertilized. Farmers must turn to chemical fertilizers, introducing pollution and triggering algal blooms that choke rivers even more. Stagnant waters also foster the spread of waterborne diseases like malaria and dengue in certain climates, particularly in slow-moving reservoirs.

And then there’s the climate close to home. Large reservoirs can alter local microclimates, increasing humidity and changing rainfall patterns, with unpredictable effects on both people and ecosystems.

Worst of all is the forced displacement of communities. Entire villages are flooded to make way for reservoirs. Families are uprooted, cultural landmarks are submerged, and people are left to rebuild their lives—often without adequate support or compensation.

In the name of “progress,” people lose their homes, their histories, and their future.

🚫 Not Cheap, Not Green: Rethinking Hydropower

To sum up, the notion that hydropower is a cheap and green energy source is, at best, misleading.

Yes—water is free. But building and maintaining a dam is not. And the hidden costs—to nature, to people, to long-term sustainability—are anything but cheap. When you factor in sediment loss, biodiversity collapse, groundwater decline, community displacement, and long-term degradation of agricultural lands, the economic equation becomes far more complex.

Hydropower is often called “clean” because it doesn’t release pollutants or CO₂ during electricity generation. But this ignores the broader ecological footprint. Dams fundamentally alter rivers, and in tropical regions, reservoirs themselves can emit large volumes of methane—a potent greenhouse gas—due to the rotting of submerged vegetation. Some of these tropical dams may contribute more to climate change than fossil fuels.

Of course, not every dam is equal. Each river system is unique. Some dams may provide net benefits under specific conditions. But many of the claimed advantages overlap, exaggerate, or mask trade-offs, and the boundaries between “green” and “destructive” grow ever blurrier.

In an era where innovative, low-impact energy sources are becoming increasingly viable, it’s worth asking: Why are we still sacrificing rivers?

This article is only the beginning. In the upcoming posts, we’ll dive deeper into the science, stories, and solutions surrounding rivers, dams, and the future of freshwater.