The Mystery of Lost Rivers: When Water Disappears Underground

Lost rivers are karst streams that vanish into sinkholes, common in the Dinaric Alps. Explore how and why they disappear in limestone landscapes.

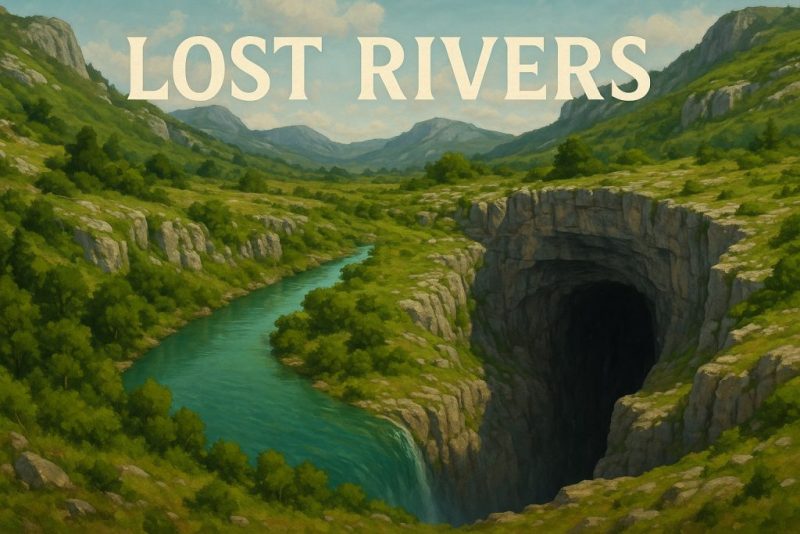

Not all rivers reach another river, lake, or the sea. Some literally vanish from the surface. Without ever making contact with the ocean, they spill out across the land and eventually evaporate—often forming inland deltas or delta. In karst landscapes, others lose their water through porous ground, slowly seeping away. And some go further still, plunging into deep sinkholes where they disappear entirely. These are known as lost rivers.

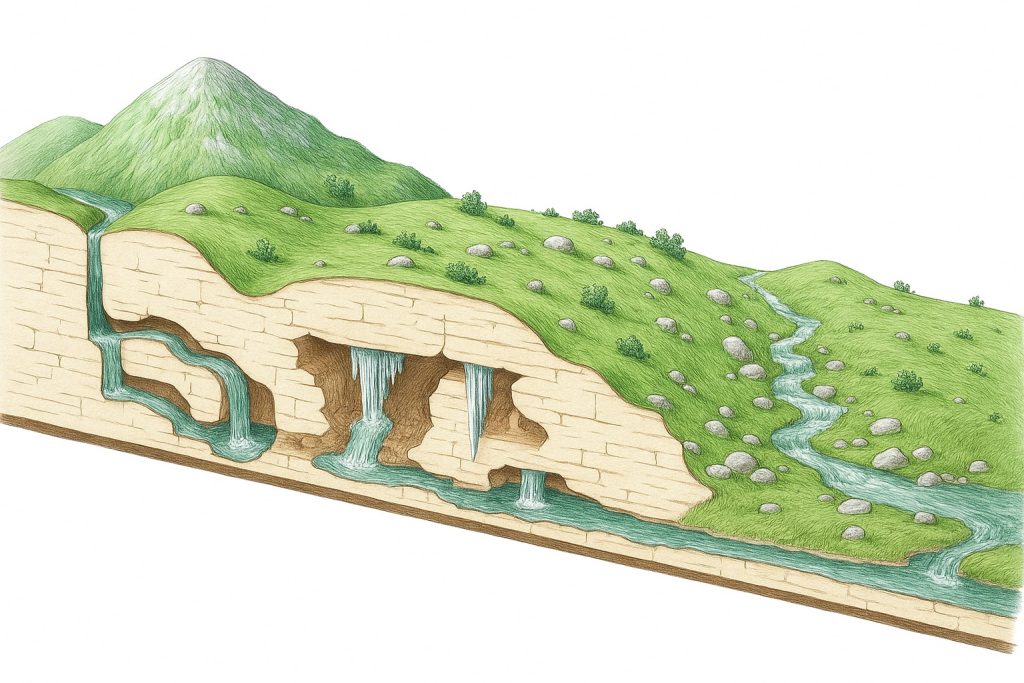

A World Built of Limestone: Karst Terrain

The Dinaric mountains—spanning across Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro—are made predominantly of limestone, a rock highly susceptible to chemical weathering. Over millions of years, slightly acidic rainwater has sculpted this stone into a jagged, pitted wonderland of cliffs, caves, and deep gorges. This kind of landscape is known as karst.

Karst terrain is porous and riddled with hidden passageways. Water doesn’t simply run across the surface—it infiltrates, trickles, carves, and flows beneath. Over time, vast subterranean systems emerge: underground rivers, sinkholes, natural bridges, and cave lakes.

Learn about tufa waterfalls—another stunning creation of rivers in karst landscapes.

Karst Poljes: The Highlands That Flood and Vanish

One of the most distinctive features of the Dinaric karst is the karst polje—broad, flat plains nestled high in the mountains. These plains are ringed by steep limestone walls and often have no visible outlet. During the rainy season, underground aquifers fill up, and water begins to rise, flooding the polje and forming temporary lakes.

Amid these poljes, a curious hydrological drama unfolds. A river may spring up at one end of the plain, flow gently across it—and then vanish. It plunges into a dark hole or a rocky crevice, disappearing from sight. This is a lost river.

Where the Water Goes: From Sinkhole to Spring

Despite their name, lost rivers are not truly lost. They merely take their journey underground. What disappears into the karst eventually reemerges elsewhere—perhaps as a karst spring, sometimes tens of kilometers away. These waters can travel through vast, labyrinthine cave systems, unseen for days, weeks, or even longer.

In fact, some of Europe’s most famous karst springs—like the Buna spring in Bosnia or Krka’s source in Croatia—may be fed, in part, by these hidden rivers.

Rivers of Stone: Dinaric Lost Rivers in Action

Across the Dinaric Alps, this phenomenon is common:

- In Lika (Croatia), the Gacka River famously disappears into a sinkhole and reemerges miles away.

- In Montenegro, rivers like Trebišnjica flow underground for long distances before surfacing.

- In Slovenia, the Planina Polje floods dramatically, with water vanishing into deep swallow holes called ponors.

These rivers only appear briefly on the surface before slipping away again—ghost rivers of the highlands.

Hidden Waters, Hidden Life: Endemic Fish of Croatia’s Lost Rivers

Beneath the quiet surfaces of Croatia’s lost rivers—Gacka, Lika, Jadova, and others—flows a secret world teeming with life. These karst rivers, known for their underground paths and seasonal rhythms, are not just geological wonders—they are ecological sanctuaries. Isolated in time and space, they shelter endemic fish species found nowhere else on Earth.

Among the most notable are:

🔹 Softmouth Trout (Salmo obtusirostris oxyrhynchus)

A unique subspecies of brown trout, this fish has adapted to the cold, slow, and oxygen-rich waters of the Gacka River. Unlike its fast-water relatives, the Gacka trout thrives in the calm, spring-fed currents that flow underground for much of their journey. It’s known for its elongated snout and silvery body, and its presence is a marker of pristine water quality.

🔹 Lika Minnow (Phoxinellus likae)

Endemic to the Lika River basin, this small, slender fish is a true karst relic, surviving in the shadows of disappearing streams. It prefers clear, shallow waters with abundant vegetation and is especially vulnerable to habitat change due to the sensitivity of its karst environment.

🔹 Jadova Minnow (Delminichthys jadovensis)

Discovered only in the tiny and seasonal Jadova River, this critically endangered species is a symbol of how fragile and isolated karst ecosystems can be. Its population is limited to just a few kilometers of river, making it one of the rarest freshwater fish in Europe.

Why It Matters: Ecosystems, Culture, and Water Security

Lost rivers are more than geological curiosities—they shape entire ecosystems. They host unique species like endemic fish, while the underground systems support rare cave-dwelling life forms. In human history, these features shaped settlement patterns, local legends, and water management techniques.

But they also pose challenges. Karst aquifers are vulnerable to pollution due to their rapid water transport and lack of filtration. Managing water in such unpredictable landscapes requires deep local knowledge and hydrological care.