The Timeless Power of River Valley Formation

The river valley is one of the most striking landforms on Earth, shaped over time by the relentless erosional power of flowing water.

River valleys are some of the most captivating and enduring features of our planet’s surface. Carved over millennia by the persistent flow of water, these natural corridors tell the story of Earth’s slow transformation. From narrow gorges to wide, fertile basins, valleys reveal the quiet yet powerful force of erosion that shapes landscapes and sustains life. In this post, we’ll explore how river valleys form, their importance in nature and human history, and why they continue to inspire awe across the world.

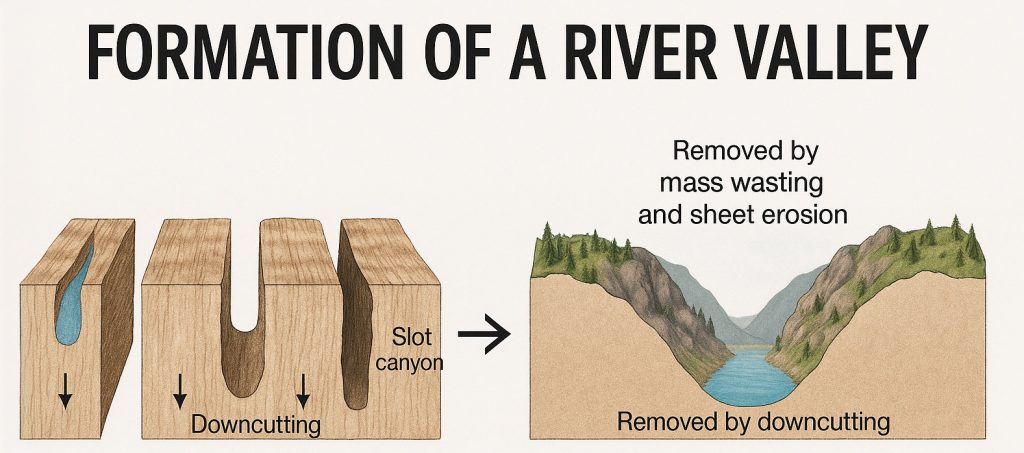

How Rivers Carve the Landscape Through Erosion and Downcutting

Rivers and streams have the power to erode the land they flow through, especially in higher altitudes. As water cuts into bedrock, it creates narrow canyons—particularly where the rock is resistant. Over time, however, mass wasting and sheet erosion break down the surrounding material, causing the stream channel to widen and extend. This ongoing process forms classic V-shaped valleys. At the heart of this transformation is downcutting—the river’s persistent action of deepening its valley floor.

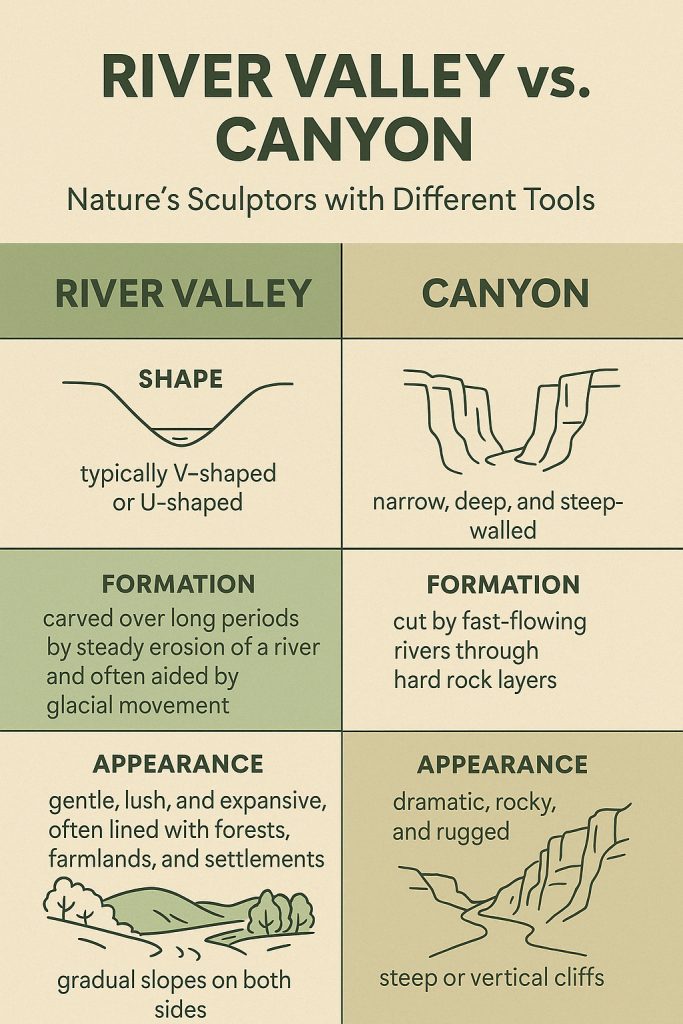

River Valley vs. Canyon: Nature’s Sculptors with Different Tools

Though both are shaped by flowing water, river valleys and canyons are quite different in appearance, formation, and character.

A river valley is typically V-shaped in its younger stages or becomes U-shaped as it ages and widens over time. It forms slowly through the steady erosion of a river, often helped along by glacial movement. River valleys are usually gentle, lush, and expansive — lined with forests, farmlands, and human settlements. Their slopes are gradual on both sides, making them easier to traverse. Classic examples include the Po Valley in Italy or the Nile Valley in Egypt.

A canyon, by contrast, is narrow, deep, and steep-walled — as if the Earth itself were sliced open. These dramatic landforms are carved by fast-flowing rivers cutting through hard rock layers, typically in arid or semi-arid regions where vegetation is sparse. The result is a rugged and rocky landscape, often featuring breathtaking vertical drops. Slopes in a canyon are usually steep or completely vertical, making them challenging to access. Famous examples include the iconic Grand Canyon in the USA and Todra Gorge in Morocco.

In essence, a valley is nature’s embrace — wide, fertile, and life-sustaining. A canyon is nature’s drama — narrow, raw, and awe-inspiring.

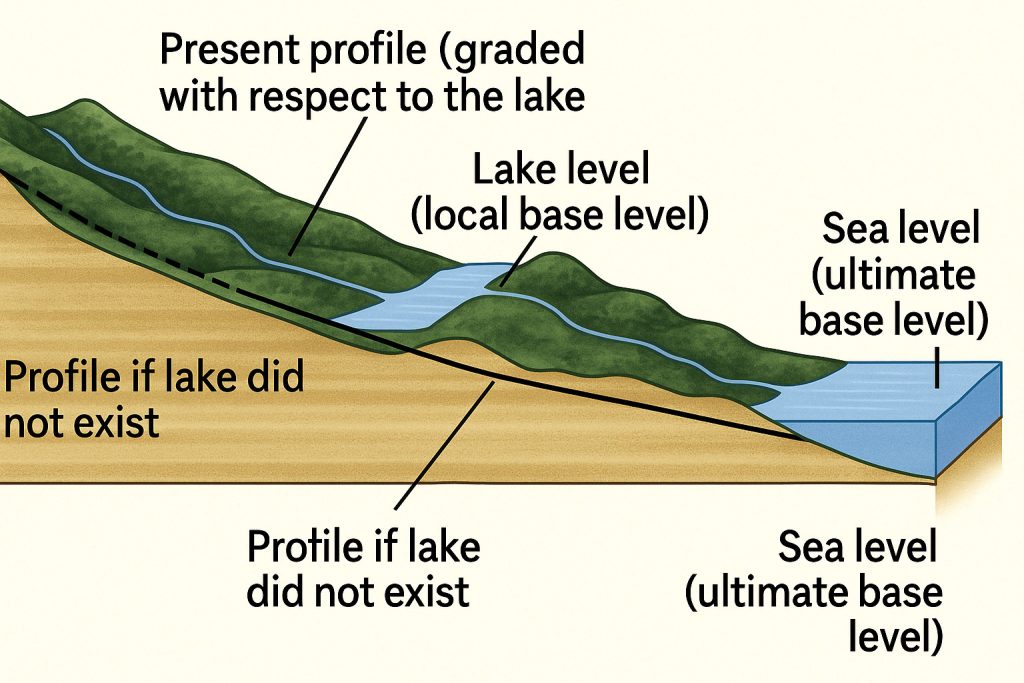

The Limits of Erosion: Understanding a River’s Base Level

Rivers may seem endlessly powerful, but their ability to cut into the land has a natural boundary — known as the base level. This is the lowest point to which a river can erode its bed. For tributaries, the base level is typically the elevation where they meet the main stream. For rivers that empty into the sea, the sea level becomes the ultimate base level.

A river cannot cut below its base level — to do so would mean flowing uphill, which is physically impossible. For most rivers and streams, sea level is the controlling factor that sets the depth to which landscapes can be eroded. However, there are exceptions. In landlocked basins, the base level is defined by the lowest point of that depression. For example, in Death Valley, California, the base level is 86 meters (282 feet) below sea level — the valley’s lowest point.

Streams at higher elevations that lie far above their base level have strong erosive power, especially when flowing over softer or fractured rock. As rivers approach their base level, the force of downcutting gradually weakens.

Over geological time, ice ages have significantly influenced base levels. During glacial periods, sea levels dropped, allowing rivers to erode deeper valleys. When glaciers melted and sea levels rose again, erosion slowed and sediment deposition became dominant. These fluctuations shaped many of the terraces and layered landscapes we see today.

In short, a river is always sculpting — but only down to a point. The base level is where gravity draws the line.

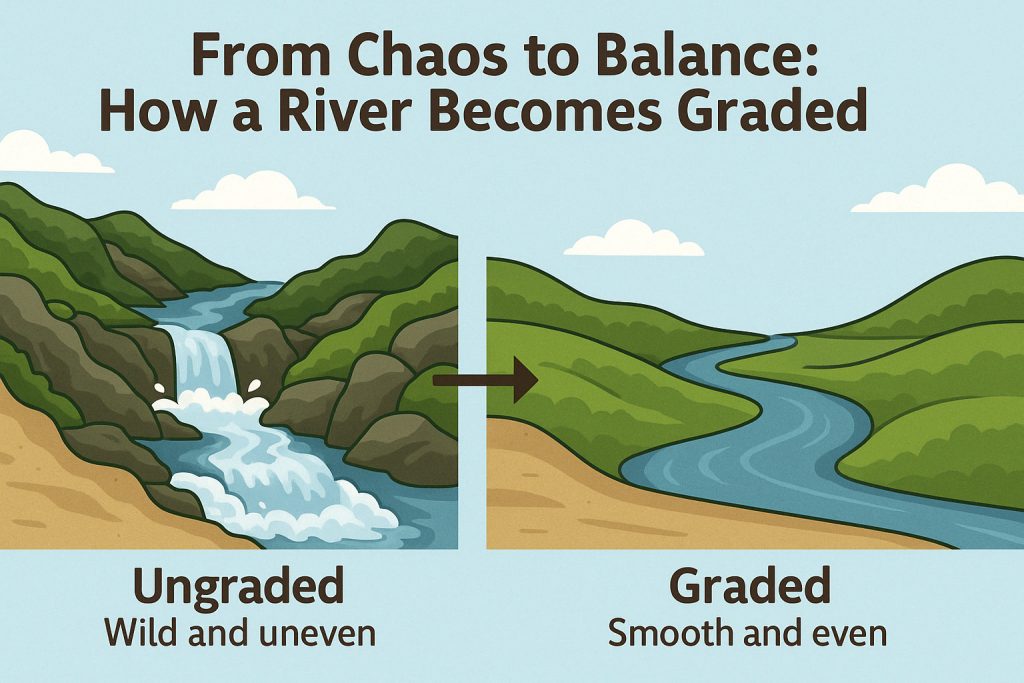

From Chaos to Balance: How a River Becomes Graded

In the early stages of its life, a river is wild and uneven — its longitudinal profile (the slope from source to mouth) is full of irregularities, such as rapids, cascades, and waterfalls. This youthful river is known as ungraded. At this stage, the stream is actively carving through the landscape, using much of its erosional energy not to deepen its bed uniformly, but rather to smooth out the bumps and abrupt drops in its course.

Over time, as erosion wears down the steep sections and sediment fills in the lower ones, the river begins to even out. Its energy is redistributed more efficiently along its length. Eventually, it reaches a more harmonious slope — a smooth, concave curve from headwaters to mouth. At this point, the river is said to be graded.

A graded river doesn’t mean it has stopped eroding or depositing sediment. Instead, it’s in a state of dynamic equilibrium — adjusting constantly to changes in discharge, sediment load, or base level, but with a profile that reflects long-term balance rather than dramatic shifts.

This transformation — from ungraded chaos to graded calm — is a key part of how rivers shape the land over geological time.

Biodiversity Hotspots: Life Flourishes Where Water Flows

River valleys are not just scenic corridors — they are vital lifelines for biodiversity. The constant presence of water, paired with rich soils and varied microclimates, makes these areas some of the most ecologically diverse habitats on Earth.

At the heart of river valley ecosystems are freshwater habitats like streams, pools, and oxbow lakes. These support an abundance of aquatic species, including fish, amphibians like frogs and salamanders, aquatic insects, and even freshwater turtles. The quality and flow of water in these zones are critical to sustaining delicate ecological balances.

Surrounding the riverbanks are wetlands — swamps, marshes, and floodplains that act like natural sponges. These wetlands not only filter pollutants and store carbon but also serve as nurseries for countless species. From dragonflies to ducks, life here thrives in the still waters and dense vegetation.

Adjacent to the river itself are riparian zones — the lush, green ribbons of land lining riverbanks. These zones are hotspots of plant diversity, with willows, reeds, and shrubs that stabilize soil and provide shade, creating cooler microhabitats crucial for aquatic life. This green corridor also acts as a wildlife highway, enabling animals to migrate safely and find food, mates, or shelter.

Many migratory birds rely on river valleys as seasonal stopovers or breeding grounds. Species such as herons, kingfishers, storks, and countless songbirds find nourishment and refuge along these watery paths. Mammals like otters, beavers, deer, and even big cats in some regions also depend on river valleys as part of their natural range.

In some parts of the world, river valleys shelter endangered species and fragile ecosystems found nowhere else — making them not only biodiversity havens but also critical conservation zones. The Amazon, the Mekong, the Nile, and the Zambezi river valleys are all examples of living worlds teeming with species that rely entirely on the unique rhythms of flowing water.

In essence, river valleys are cradles of life — where earth, water, and sunlight meet to nurture a symphony of species.

Shaped by Water, Transformed by People: Human Influence on River Valleys

River valleys are often referred to as the cradles of civilization. The fertile soils and reliable water supply of the Nile Valley (Egypt), Tigris-Euphrates Valley (Mesopotamia), Indus Valley (India/Pakistan), and Yellow River Valley (China) allowed ancient societies to flourish thousands of years ago.

While rivers have been carving valleys for millions of years, today it’s often humans who do the shaping. In mountainous regions, where steep slopes dominate the landscape, the relatively flat bottoms of river valleys are often the only suitable places to build and live. These narrow strips of level ground become crucial zones for settlements, agriculture, industry, as well as roads and railways — the lifelines that connect remote areas.

However, this convenient relationship between people and rivers also comes with challenges. Natural river systems are dynamic — they flood, shift, and erode their banks over time. To protect infrastructure and farmland, rivers are often regulated: their banks are reinforced, their courses straightened, and their floodplains constrained. These interventions aim to reduce flooding and erosion, making the valleys more predictable and safer for human activity.

Additionally, many rivers are dammed — not just to tame their power, but to harness it. Dams transform valleys into reservoirs, supplying water for drinking, irrigation, and hydroelectric power. While these dams generate clean energy, they also dramatically alter ecosystems, sediment flow, and the very landscape of the valleys they occupy.

In short, river valleys today are no longer solely the product of water and time — they are shared spaces, co-created by nature and human ambition. The balance between preserving natural processes and accommodating human needs continues to shape the future of these vital landscapes.

River Valleys: Nature’s Life Lines

River valleys are the sculpted masterpieces of flowing water — winding paths carved through stone and soil, connecting mountains to seas. They are the birthplaces of civilizations, the veins of ecosystems, and vital arteries of both nature and human life.

Over time, rivers cut deep, shape the land, and leave behind fertile soils, sustaining crops, forests, and entire cultures. Their dynamic landscapes evolve with every drop of rain and shift of earth — from roaring canyons to gentle floodplains. These valleys are home to extraordinary biodiversity, and their calm waters have long been mirrors to the story of life.

Today, we live, work, and thrive in their embrace — shaping them as they once shaped us. River valleys are not just features of geography — they are the timeless meeting place of water, life, and civilization.