Rivers in England: Facts and Figures

Discover rivers in England—from the winding Thames to hidden rural streams. Explore key facts, figures, and what makes these waterways so unique.

England’s rivers have shaped the country’s landscape and history for millennia. For instance, rivers played a crucial role in facilitating the Viking raids of the 9th and 10th centuries.

These waterways, ranging from gentle streams to powerful currents, have played a crucial role in the development of settlements, industry, and culture. Rivers in England continue to have an impact on the environment, economy, and daily life of its inhabitants.

The rivers of England offer a fascinating subject for students and nature enthusiasts alike. This article explores the major waterways, their geographical distribution, and their unique characteristics. It also delves into these rivers’ historical significance and importance to the environment. By examining these aspects, readers will gain a comprehensive understanding of England’s riverine network and its enduring influence on the nation.

Major Rivers in England

Numerous rivers shape England’s landscape, each with its own unique characteristics and significance. Three of the most prominent rivers stand out: the Thames, the Severn, and the Trent. These waterways have played a crucial role in shaping the country’s geography, history, and culture.

River Thames

The River Thames, England’s longest river, stretches for 215 miles (346 km) from its source in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds to its estuary on the North Sea at Southend-on-Sea. This majestic waterway flows through eight English counties, including Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Surrey, Essex, and Kent.

The Thames has an ancient history, with its name being of Celtic origin. Originally known as Tameses, meaning dark or muddy coloured, historians hailed it as the oldest place name in Great Britain. Interestingly, in Oxford, the river is referred to as the Isis, a name that stems from Victorian times and is believed to have an impact on the river’s identity in that region.

The river has an influence on numerous settlements along its course, including the metropolis of London and the city of Oxford. Other notable locations include Richmond, Reading, Kingston, Marlow, Henley, and Windsor. The Thames significantly impact the environment, serving as a vital water source and habitat for various species. In its non-tidal waters, the river is home to Harbour Seals, Grey Seals, and around 25 species of course fish.

River Severn

The River Severn holds the distinction of being the longest river in Great Britain, with a length of 220 miles (354 km). It also has the most voluminous flow of water in England and Wales, with an average flow rate of 107 m3/s (3,800 cu ft/s) at Apperley, Gloucestershire.

The Severn begins its journey in the Cambrian Mountains of mid-Wales and is fed by 21 tributaries before reaching the Bristol Channel. Along its course, the river passes through four counties: Powys in Wales, and Shropshire, Worcestershire, and Gloucestershire in England. The Severn’s major tributaries include the Vyrnwy, the Tern, the Teme, the Warwickshire Avon, and the Worcestershire Stour.

One of the most fascinating features of the River Severn is its tidal bore, a phenomenon associated with its lower reaches. The river’s estuary has a remarkable tidal range of 48 feet (15 m), which is frequently asserted to be the second largest in the world, exceeded only by the Bay of Fundy.

River Trent

The River Trent is the third longest river in the United Kingdom, with a length of 185 miles (297 km). Its source is in Staffordshire, on the southern edge of Biddulph Moor, and it flows through the North Midlands before draining into the Humber Estuary.

The Trent passes through several notable towns and cities, including Stoke-on-Trent, Stone, Rugeley, Burton-upon-Trent, and Nottingham. It eventually joins the River Ouse in Yorkshire at Trent Falls to form the Humber Estuary, which empties into the North Sea.

The river’s name, “Trent,” is possibly derived from a Romano-British word meaning “strongly flooding”. This etymology may indicate the river’s tendency to cause significant flooding along its course, with a well-documented flood history extending back some 900 years.

The Trent basin covers a large part of the Midlands, including the majority of Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, and the West Midlands, as well as parts of Lincolnshire, South Yorkshire, Warwickshire, and Rutland. The river is tidal for 50 miles (80 km) up to Cromwell Lock, 3 miles (5 km) below Newark, and at spring tide, a bore known as the eagre develops, with a wave front of 3 to 4 feet (about 1 metre).

These three major rivers – the Thames, Severn, and Trent – continue to have an impact on England’s landscape, ecology, and economy. They serve as vital waterways for transportation, sources of water for agriculture and industry, and habitats for diverse wildlife, making them essential subjects of study for those interested in England’s natural history.

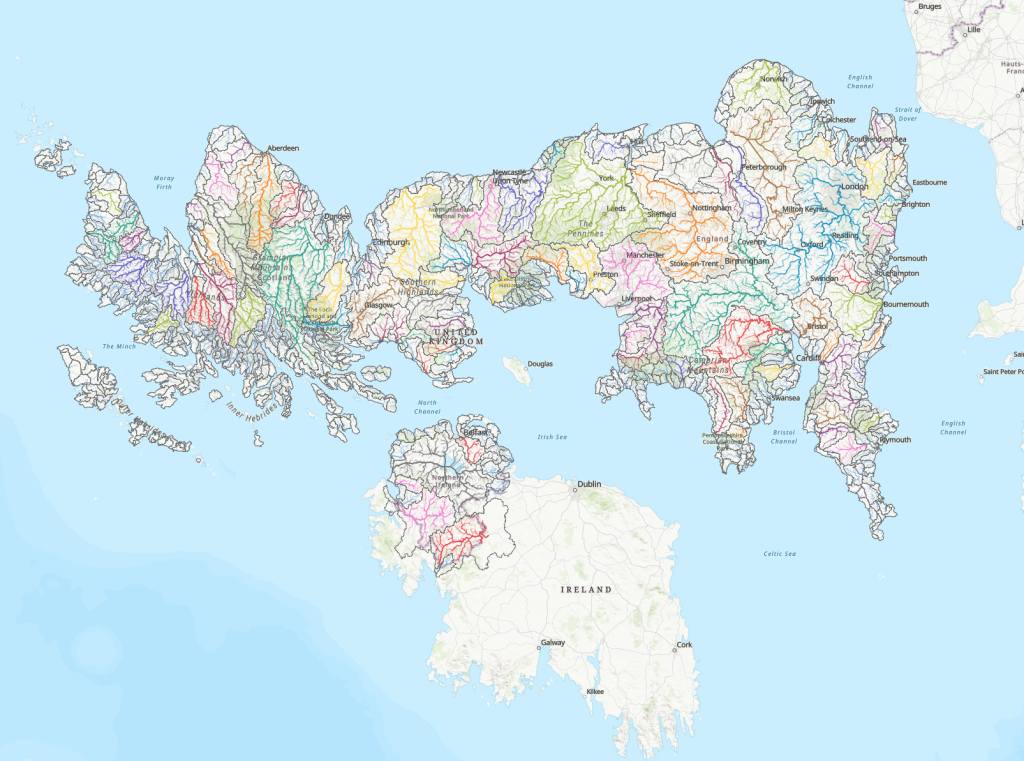

Geographical Distribution of Rivers

England’s rivers form an intricate network that shapes the country’s landscape and significantly impacts its geography, ecology, and human settlements. Understanding the distribution of these waterways offers valuable insights into the nation’s natural history for students and nature history buffs.

Northern England

The rivers in Northern England play a crucial role in defining the region’s topography and have historically influenced the development of local industries and communities. While specific information about Northern England’s rivers is limited in the provided data, it’s important to note that this region is home to several significant waterways that contribute to the country’s overall river system.

Midlands

The Midlands region is characterised by a diverse river network that has shaped its landscape and supported human activities for centuries. The River Trent, one of England’s major waterways, flows through the North Midlands for 185 miles (297 km). Its source is in Staffordshire, on the southern edge of Biddulph Moor, and it eventually joins the River Ouse in Yorkshire to form the Humber Estuary.

The Trent passes through several notable towns and cities, including Stoke-on-Trent, Stone, Rugeley, Burton-upon-Trent, and Nottingham. Its basin covers a substantial part of the Midlands, encompassing the majority of Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, and the West Midlands, as well as parts of Lincolnshire, South Yorkshire, Warwickshire, and Rutland.

Another significant river in the Midlands is the River Avon, also known as the Warwickshire Avon. It flows through several counties and has features that attract canoeists and kayakers. Notable locations along the Avon include:

The River Derwent, flowing through the Peak District, is another important waterway in the Midlands. It offers various sections for canoeing and kayaking, including:

Southern England

Southern England is home to one of the country’s most iconic rivers, the Thames. Stretching for 205 miles (330 km), the Thames runs 140 miles (226 km) from its source at Thames Head to the tidal waters limit at Teddington Lock. From there, it continues as an estuary for another 65 miles (104 km) to The Nore sandbank, marking the transition from estuary to open sea.

The Thames Basin has a complex structure, receiving an annual average precipitation of 27 inches (688 mm). In its upper course, the river drains a broadly triangular area defined by the chalk escarpment of the Chiltern Hills and the Berkshire Downs to the east and south, the Cotswolds to the west, and the Northamptonshire uplands to the north.

At Goring Gap, the Thames cuts through the chalk escarpment and then drains the land north of the North Downs dip slope. Its last great tributary, the River Medway, drains much of the low-lying Weald area of Kent and Sussex to the south of London.

The Thames is characterised by its gentle flow through rolling lowlands, with an average fall of less than 20 inches per mile (32 cm per km) between Lechlade and London. The tidal influence begins to be felt intermittently at Teddington in west London, with the transition from freshwater to estuarine reaches occurring around Battersea in central London.

To protect London from potential flooding, the Thames Barrier was constructed at Silvertown (completed in 1982), along with extensive complementary flood defences along the entire tideway.

Characteristics of English Rivers

While relatively small on a global scale, English rivers possess unique characteristics that have shaped the country’s landscape and history. Understanding these features provides valuable insights into England’s natural heritage for students and nature history buffs.

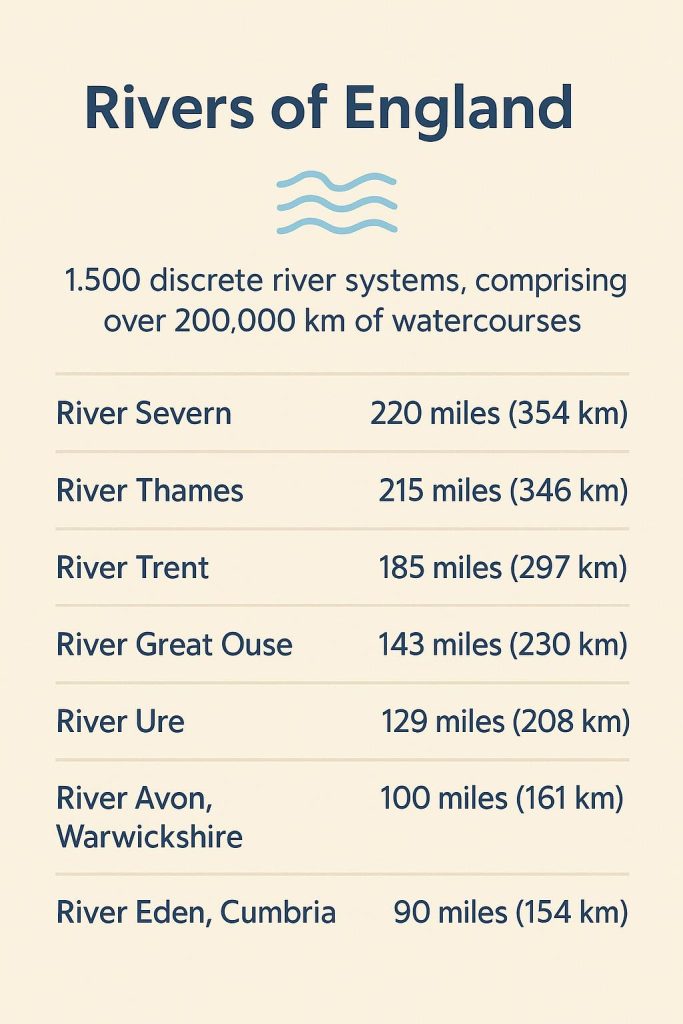

Length

The rivers of England are characteristically short compared to their global counterparts. The River Severn, the longest river in the United Kingdom, stretches for only 220 miles (354 km). This modest length is typical of English rivers, with the River Thames, the second-longest, measuring 215 miles (346 km). The River Trent, another major waterway, extends for 185 miles (297 km).

Other notable rivers in England include:

- River Great Ouse: 143 miles (230 km)

- River Ure/River Ouse, Yorkshire: 129 miles (208 km)

- River Nene: 100 miles (161 km)

- River Avon, Warwickshire: 96 miles (154 km)

- River Eden, Cumbria: 90 miles (145 km)

These lengths reflect the compact nature of England’s geography, with rivers efficiently draining the landscape despite their relatively short courses.

Flow Rate

The flow rates of English rivers vary considerably, influenced by factors such as rainfall, geology, and catchment area. The River Severn has the highest average discharge among English rivers, with a mean flow of 107.4 m³/s. This is followed by the River Trent at 89.0 m³/s and the River Thames at 65.4 m³/s.

Other significant flow rates include:

- River Ure/River Ouse, Yorkshire: 69.8 m³/s [8]

- River Tyne: 45.2 m³/s

- River Eden, Cumbria: 53.7 m³/s

- River Aire: 36.5 m³/s

- River Mersey: 37.1 m³/s

It’s important to note that these flow rates can fluctuate significantly. River flows in England can range through several orders of magnitude, with low flows tending to be very modest in most river basins.

Drainage Basins

The drainage basins of English rivers, while smaller than those of major global rivers, play a crucial role in shaping the country’s hydrology. The United Kingdom has almost 1,500 discrete river systems, comprising over 200,000 km of watercourses. These basins vary widely in size and characteristics, reflecting the diverse geology and climate of England.

Some notable drainage basins include:

- Humber drainage basin: Encompasses several major rivers, including the Trent and Ouse

- Thames drainage basin: Covers a significant portion of southeast England

- Severn drainage basin: Extends across parts of both England and Wales

- Mersey catchment: An important basin in northwest England

- Tyne catchment: A significant basin in northeast England

The geological characteristics of individual catchments, particularly their permeability, have a major influence on river flow patterns. For example, rivers draining chalk aquifers, like the River Lambourn in the Thames basin, exhibit more stable flow regimes compared to those draining impermeable clay catchments, such as the River Ock.

These diverse drainage basins contribute to the unique character of English rivers, creating a rich tapestry of aquatic ecosystems and landscapes that have shaped the country’s natural and cultural history.

Historical Significance of Rivers

Transportation

Rivers have played a crucial role in the development of transportation networks in England, serving as vital arteries for the movement of goods and people. Before the advent of modern roads and railways, water transport was the most efficient and economical method of transportation. Major navigable rivers such as the Humber, Mersey, Yorkshire Ouse, Severn, Thames, and Trent formed the backbone of this transportation system.

The importance of water transport in Britain’s economic development cannot be overstated. Before the Industrial Revolution, the movement of goods from production sites to areas of demand was essential for a functioning economy. While land-based transport using horses had limited quantity, fragility, and freshness of goods, water transport offered greater capacity and speed.

Water-borne trade in Britain comprised three key aspects: sea, coastal, and river transport. Overseas trade, conducted through large ships, was crucial for importing and exporting goods and raw materials. Several key British ports, including London, had been growing on trade even before the industrial boom, with many traders contributing to the construction of public buildings.

Coastal trade was particularly significant due to its cost-effectiveness compared to road transport. Between 1650 and 1750, before the Industrial Revolution, approximately half a million metric tonnes of coal were transported annually from Newcastle in the north to London in the south via coastal routes.

Industrial Revolution

The advent of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century brought about a surge in demand for more efficient and reliable transportation methods. This need led to the development of the modern canal network in Britain. The canals proved to be an economic and dependable way to transport goods and commodities in large quantities, addressing the limitations of the emerging road system and the traditional use of packhorses.

The construction of major canals began in the 18th century, linking key manufacturing centres across the country. These new waterways proved highly successful, utilising a horse-drawn system with towpaths alongside the canals. This method was remarkably economical and became the standard across the British canal network.

The canal system expanded rapidly, eventually forming an almost completely connected network covering the South, Midlands, and parts of the North of England and Wales. This extensive network played a vital role in facilitating the movement of raw materials and finished products, thereby fuelling the nation’s industrial growth.

Urban Development

Rivers and canals have had a significant impact on urban development in England. The establishment of water mills in the Middle Ages dramatically increased riverside settlements. These mills, serving as the main energy source of the time, became focal points for community growth and economic activity.

The industrial era saw further intensification of river use, with increased demands for hydroelectric power, process water, and transportation routes provided by waterways. This led to the development of industrial towns and cities along major rivers and canals, shaping the urban landscape of England.

Riverside development on the Aire near Leeds Bridge

However, the relationship between rivers and urban areas has not always been harmonious. The last two centuries have seen significant morphodynamic impacts on fluvial systems due to changes in land use, industry, flood protection measures, drinking water supply, and hydroelectric power generation. For instance, the channelization of rivers like the alpine Rhone, Isar, and Danube in the mid- to late-nineteenth century caused significant changes in river structures.

From after World War II until the early 1980s, the focus was on reclaiming floodplains for agriculture and expanding settlements, further altering the natural river landscapes. These changes have had lasting effects on the rivers and the urban areas that developed around them, highlighting the complex interplay between natural water systems and human development.

Environmental Importance of Rivers

Rivers play a crucial role in shaping the landscape and supporting diverse ecosystems. For students and nature history buffs, understanding the environmental significance of rivers offers valuable insights into the intricate balance of our natural world.

Biodiversity

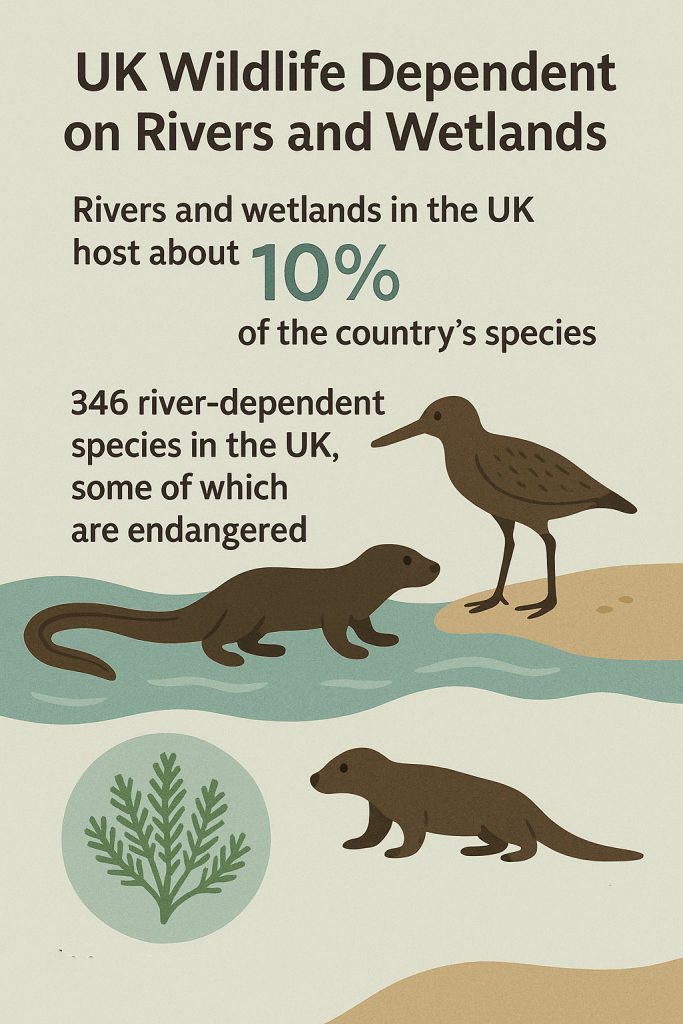

Rivers and their floodplains are among the most important environments in the UK, supporting a disproportionate level of biodiversity relative to their size within landscapes. Despite covering less than 1% of Earth’s surface, freshwater bodies, including rivers, are home to approximately 40% of all fish species and around a third of described vertebrate species globally.

The Environment Agency reports that rivers and wetlands in the UK host about 10% of the country’s species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has identified 346 river-dependent species in the UK, some of which are endangered. These include eels, otters, the bar-tailed godwit, and feather mosses.

The diversity of river habitats contributes to their rich biodiversity. A short stretch of lowland river can feature up to 10 different habitats, including pools, riffles, glides, backwaters, and floodplains, each supporting a unique repertoire of species. England is also home to 170 of the world’s 210 chalk streams, which are rare and internationally important habitats characterised by their gravel and flint beds and crystal clear water.

Recent studies have shown encouraging trends in river biodiversity. A comprehensive analysis over 30 years found significant improvements in river invertebrate biodiversity across all regions and river types in England. The average number of freshwater invertebrate families found at each site increased from 15 to 25 between 1989 and 2018, representing a 66% increase.

Water Resources

Rivers serve as vital sources of fresh water for various human activities and natural processes. In the UK, water companies abstract approximately 4.6 cubic kilometres of water from rivers, lakes, and reservoirs in England annually for public supply. This water is used for drinking, bathing, irrigation, and various domestic and industrial purposes.

However, the demand for water resources can lead to over-abstraction, which affects river health. The UK government estimates that about one in five surface water sources are depleted due to excessive abstraction. This depletion has significant implications for the river ecosystems and the species that depend on them.

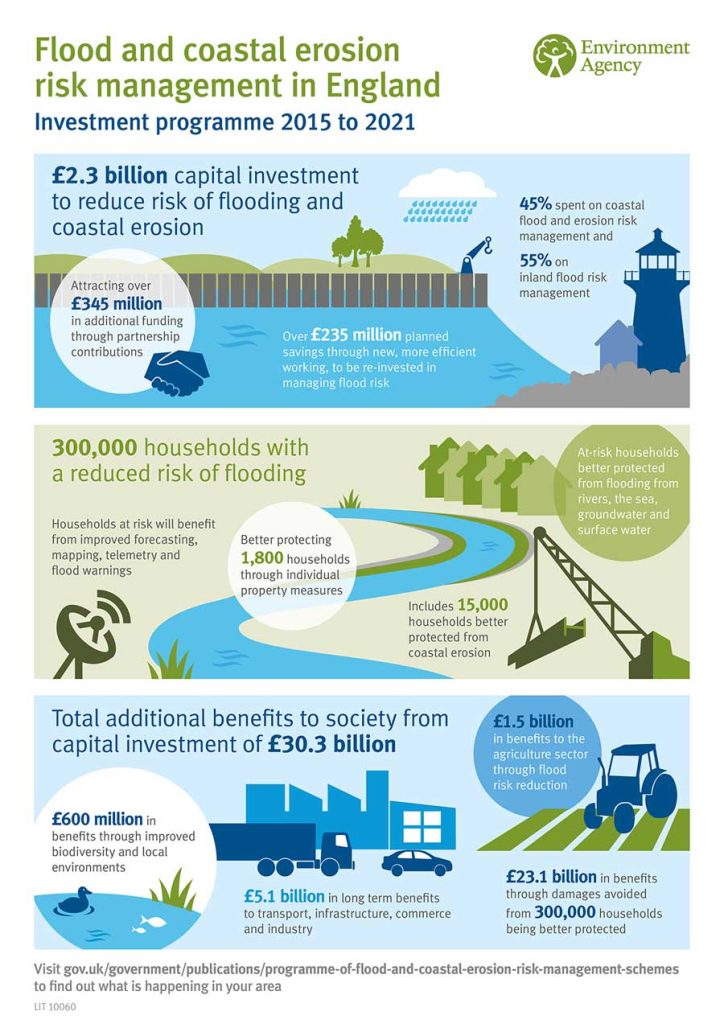

Flood Management in England: Holding Back the Tide

England, a country etched with rivers, ancient floodplains, and a famously moody sky, has long grappled with the elemental power of water. From the quiet meandering of the Thames to the sudden fury of flash floods in Cumbria, the challenge of flood management is as old as the land itself. Yet today, as climate change intensifies rainfall and sea levels inch higher, flood defences have evolved from simple dykes and levees into a sophisticated blend of technology, natural engineering, and community resilience.

Defending the Land: Hard Engineering Solutions

At the heart of England’s flood management strategy are robust infrastructure projects. These include towering concrete flood barriers, embankments, and pumping stations engineered to divert or contain rising waters. The Thames Barrier, a marvel of 20th-century engineering, stands sentinel across the river just downstream of central London. Since its completion in 1982, it has been raised hundreds of times to shield the capital from tidal surges.

Elsewhere, towns and cities now rely on flood alleviation schemes, such as retention basins, raised riverbanks, and sluice gates. These are designed not only to protect properties but also to manage the increasingly unpredictable hydrological patterns of Britain’s wet seasons.

Working With Nature: Soft Engineering & Rewilding

But the future of flood defence in England lies not just in concrete, but in reconnecting rivers with their floodplains. Natural flood management (NFM) schemes are rising in popularity, particularly in rural and upland areas. These include reforesting river catchments to slow runoff, restoring wetlands that act like natural sponges, and even allowing rivers to braid and meander once more.

Projects like the Pickering “Slowing the Flow” initiative in North Yorkshire show how planting trees and building woody debris dams can reduce flood peaks without disrupting the landscape’s character. These approaches offer a double win: they boost biodiversity and carbon capture while shielding homes and farmlands from devastation.

Forecasting & Community Resilience

Modern flood management in England is as much about foresight as force. The Environment Agency, alongside the Met Office, now uses high-resolution data, AI-powered models, and live river level monitoring to issue timely flood alerts. These digital tools, accessible via apps and text alerts, give residents precious hours to move valuables, deploy sandbags, or evacuate.

At the community level, Flood Action Groups have emerged across the country—from Somerset to Shrewsbury—creating localised networks of support and preparedness. Education campaigns, property-level flood resistance (like raised electrical sockets and non-return valves), and emergency planning are all part of a new mindset that sees flooding not as a rare anomaly, but as a recurring reality to be met with calm readiness.

A Shifting Tide

England’s approach to flood management today is layered: a complex interplay of tradition and innovation, of controlling water and learning to live with it. As rainfall records are broken and coastal erosion accelerates, the challenge will be to stay one step ahead. Whether through resilient cities, adaptive architecture, or wild wetlands restored to life, the goal is no longer just to hold back the flood—but to shape a landscape that can flow with it.

Conclusion

England’s rivers have a lasting influence on the country’s landscape, history, and environment. From the mighty Thames to the winding Severn, these waterways have shaped settlements, fueled industry, and fostered diverse ecosystems. Their role in transportation, urban growth, and flood management underscores their significance to both human activities and natural processes. For students and nature history buffs, these rivers offer a wealth of knowledge to explore, from their unique characteristics to their environmental importance.

As we’ve seen, English rivers continue to have an impact on biodiversity, water resources, and flood control. Their ability to support a wide range of species and provide essential services highlights the need for careful management and conservation. By understanding the complex relationships between rivers and their surroundings, we can better appreciate their value and work towards their preservation for future generations. To keep learning about England’s natural wonders, check out more articles on our website.

FAQs

What should I know about the UK’s rivers?The UK boasts roughly 90,000 km of rivers spread across the nation, with only 3% achieving a High Status classification.

Can you share five fascinating facts about rivers?Rivers are among the most biologically diverse ecosystems on Earth. They play a crucial role in feeding populations, have been pivotal in the development of civilisations, and have shaped the Earth’s landscapes beautifully. However, dams have disrupted two-thirds of the world’s major rivers.

Which are the primary rivers in England?England’s two longest rivers are the River Severn, located in the southwest, and the River Thames, which flows through London and is the deepest river in the UK.

What are some interesting details about England’s longest river?The River Severn, stretching 360 km, is not only the longest river in the UK but also the most voluminous. It originates in the Cambrian Mountains in mid-Wales and is fed by twenty-one tributaries before it reaches the Bristol Channel.