Rivers of Africa – From Catchment to Civilization

Explore Africa’s rivers—from the Nile to the Zambezi. Discover their basins, ecology, civilizations, economic role, and the threats they face.

From misty equatorial jungles to desert sands and savannahs, rivers have always defined Africa. They are not just flows of water—they are arteries of biodiversity, the cradles of ancient empires, and the foundation of economies. In this guide, we explore Africa’s rivers through the lens of geography, hydrology, ecology, human history, and the growing threats to their existence.

🗺️ Geography and Geology of Africa’s Rivers

The Plateau Continent’s Watery Puzzle

Africa is often called the Plateau Continent, and this defining geological feature profoundly shapes the character of its rivers. Unlike other continents where rivers meander gently across lowlands, Africa’s rivers are born high and fall fast. The interior of the continent is dominated by elevated plateaus, often thousands of meters above sea level, which suddenly drop toward the coast in dramatic escarpments—natural staircases carved by ancient tectonic uplift.

This plateau structure means that rivers rarely follow a straight or predictable course. Instead, they plunge through deep valleys, rocky gorges, and narrow canyons, often tumbling over dramatic waterfalls and rapids. Rivers like the Zambezi, with its thunderous descent over Victoria Falls, or the Congo, which cuts through the Stanley Pool and Inga Rapids, are powerful examples of how Africa’s terrain channels water with both violence and beauty.

In many places, these features render rivers non-navigable, breaking them into disconnected segments. The Congo River is an exception, offering long navigable stretches in its interior basin—but even it is interrupted by violent cataracts near its mouth.

Geologically, Africa is ancient. The bedrock beneath its rivers dates back billions of years, made up of some of the oldest continental crust on Earth. Rivers such as the Orange and the Limpopo have cut into these crystalline shields over eons, exposing ancient rock and forming some of the most stable yet eroded river valleys in the world.

Africa also differs in the distribution of freshwater lakes, which are relatively few compared to other continents like North America or Europe. While the Great Lakes of East Africa—Victoria, Tanganyika, and Malawi—play crucial hydrological roles, many of Africa’s major rivers do not originate from vast lakes. Instead, they arise in humid highlands or seasonally flooded zones, fueled by tropical rainfall belts, especially those influenced by the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

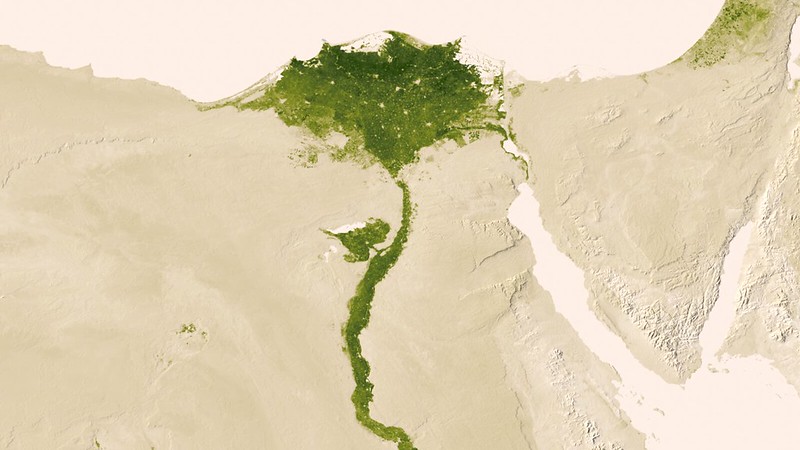

Once they begin their descent, Africa’s rivers traverse some of the most contrasting landscapes on Earth—rushing from mist-shrouded rainforests to sun-baked savannahs, winding through parched deserts and spilling into fertile wetlands. The Nile, for instance, begins in the green hills of Rwanda and Uganda, only to pass through some of the driest terrain on the planet in Egypt and Sudan. The Niger starts in lush Guinea and makes an improbable loop through arid Sahel, eventually forming a vast inland delta in Mali before reaching the Gulf of Guinea.

In essence, the rivers of Africa are not only shaped by the land—they reveal the land’s very bones. Each bend, each fall, each detour is a geological signature, written in water across the ancient face of the continent.

Major Drainage Basins and Catchments

The Arteries of a Continent

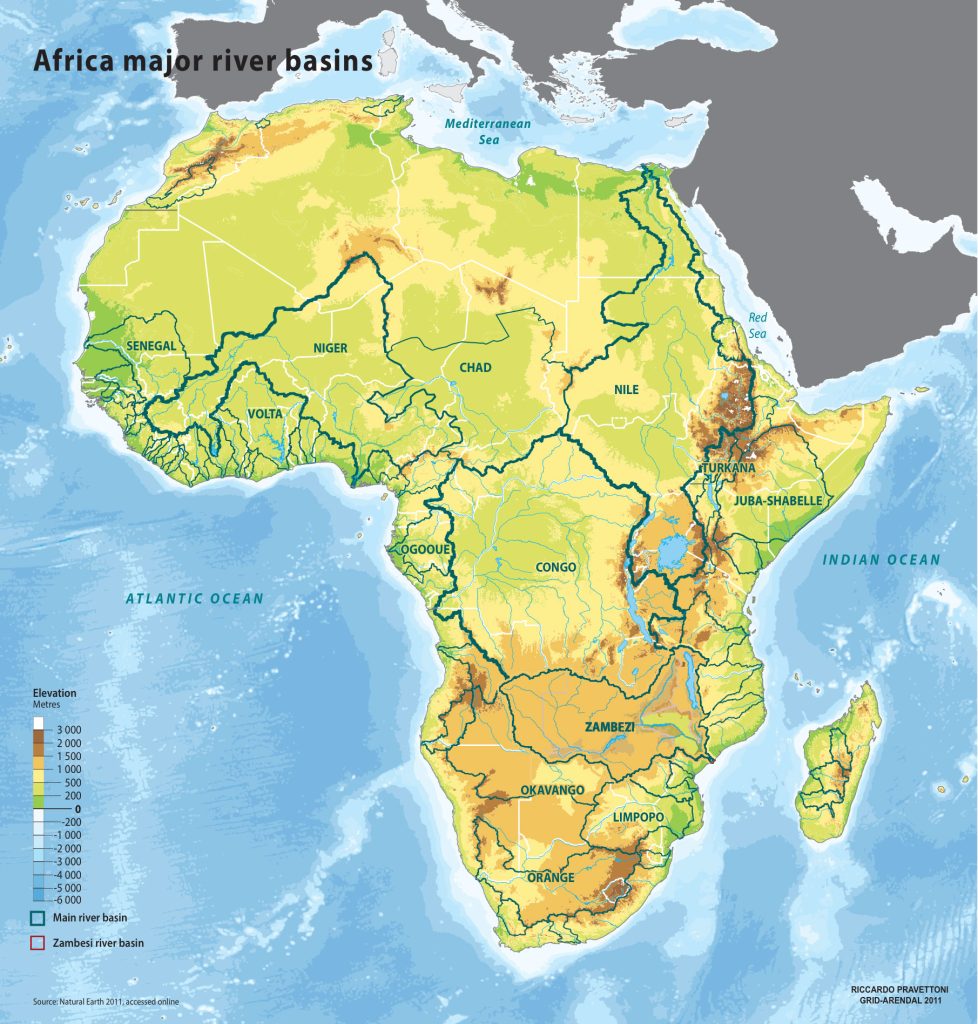

Africa’s immense landmass is drained by five major river basins, each with its own distinct geography, climate, and ecological character. These basins define the way water flows across the continent—toward the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, or, in some cases, nowhere at all.

Together, these basins cover more than 60% of Africa’s surface, shaping ecosystems, cultures, and economies across thousands of kilometers.

1. The Nile Basin

Drainage area: ~3.4 million km²

Outflow: Mediterranean Sea

Countries: Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, South Sudan, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt

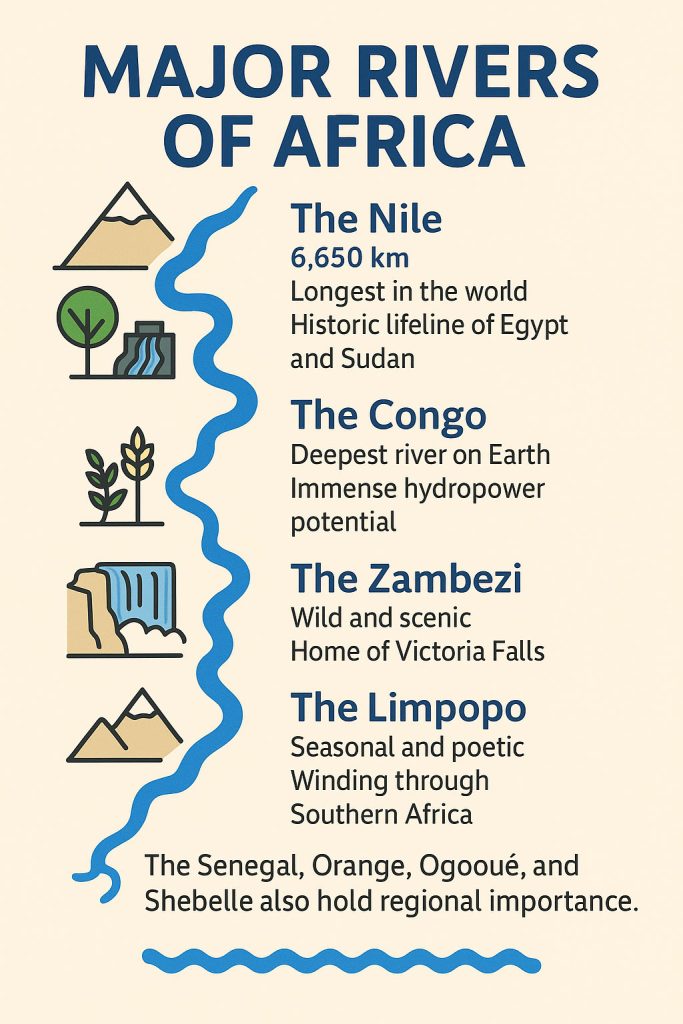

The Nile River system is the most famous and historically significant in Africa. Stretching over 6,650 km, it’s the longest river in the world. The basin begins in the humid highlands of East and Central Africa, with the White Nile originating near Lake Victoria and the Blue Nile rising from Ethiopia’s highlands.

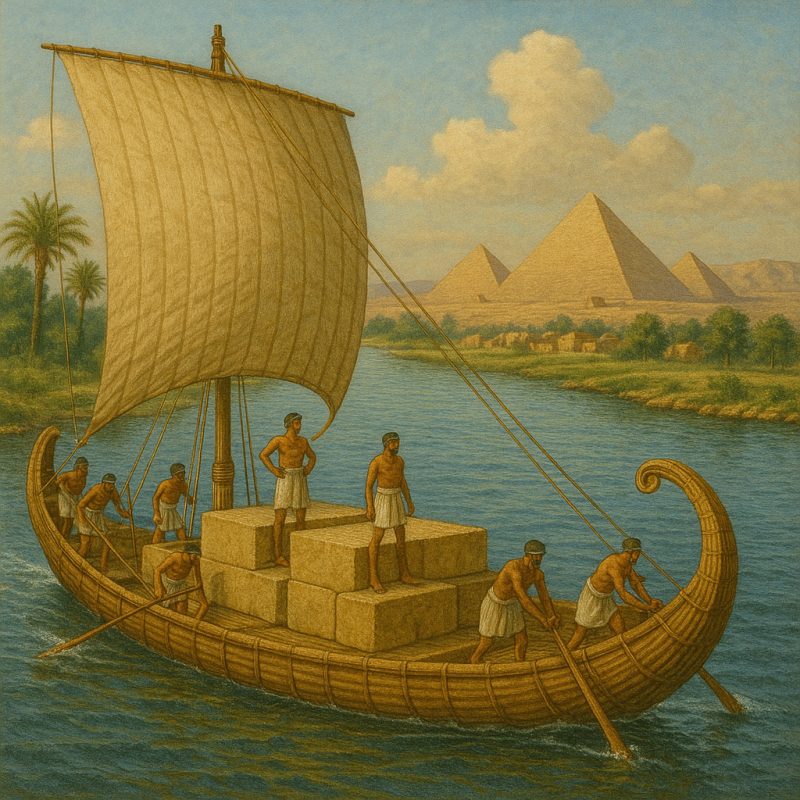

The river flows northward, cutting through deserts and fertile valleys, before reaching the Mediterranean. It has sustained agriculture and civilization for over 5,000 years, especially in the Nile Valley of Egypt.

2. The Congo Basin

Drainage area: ~4.0 million km²

Outflow: Atlantic Ocean

Countries: Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Angola, Zambia, Central African Republic, Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania

The Congo Basin is Africa’s largest by discharge and second in the world by volume, trailing only the Amazon. It contains the world’s second-largest tropical rainforest, a biodiversity hotspot of global importance.

Fed by countless tributaries and cradled by the equatorial rainforest, the Congo River flows in a vast arc across Central Africa. Its depths reach over 220 meters, making it the deepest river on Earth.

3. The Niger Basin

Drainage area: ~2.1 million km²

Outflow: Gulf of Guinea (Atlantic Ocean)

Countries: Guinea, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire

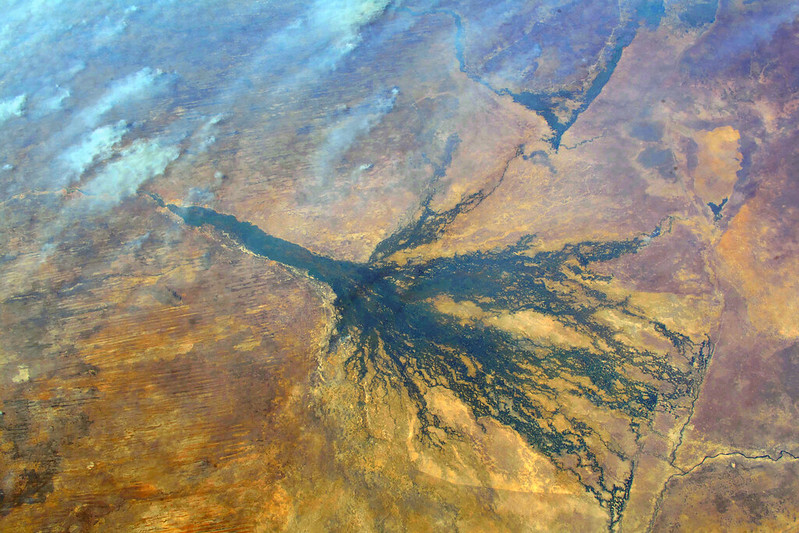

The Niger River forms a curious crescent-shaped loop—rising in the Guinean highlands, then arching northeast into the Sahel before veering southeast to empty into the Niger Delta.

Its basin cuts through arid and semi-arid zones, supporting over 130 million people, especially in cities like Bamako, Niamey, and Lagos. Seasonal floods enable traditional farming systems, like the Mali Inland Delta, a vast wetland oasis.

4. The Zambezi Basin

Drainage area: ~1.4 million km²

Outflow: Indian Ocean

Countries: Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania, Namibia, Botswana

The Zambezi River is a spectacular watercourse of southern Africa, best known for Victoria Falls—Mosi-oa-Tunya, “The Smoke That Thunders.” It flows 2,574 km eastward to the Indian Ocean, supplying water to massive hydropower projects like Kariba Dam and Cahora Bassa.

This basin features a mix of forests, savannahs, wetlands, and highland plateaus, with abundant wildlife and crucial agricultural lands along its floodplains.

5. The Orange–Limpopo Basin

Combined drainage area: ~1.0 million km²

Outflows:

- Orange River → Atlantic Ocean

- Limpopo River → Indian Ocean

Countries (combined): South Africa, Lesotho, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique

In southern Africa, two distinct river systems are often grouped together for their dryland drainage nature. The Orange River, rising in Lesotho’s highlands, is the longest in southern Africa and a lifeline for irrigation and mining across arid regions.

The Limpopo River, made famous in African literature and folklore, is a seasonal river draining semi-arid areas, with a strong flood pulse during the rainy season. These basins play a vital role in managing scarce water resources.

🏜️ Endorheic and Disappearing Systems

Not all African rivers reach the sea. Some flow into endorheic basins, such as the Lake Chad Basin (~2.5 million km²), where water either evaporates or seeps into the ground. Others vanish into sand or stone, like the seasonal wadis of the Sahara.

These systems, while not as prominent as the big five, are often critically important for pastoralists, desert wildlife, and migratory birds.

💧 Hydrology of African Rivers

The Pulse of a Continent

Africa’s rivers flow not just through landscapes—but through seasons, storms, and silence. They mirror the continent’s climatic extremes and variability, resulting in some of the most diverse and dynamic hydrological systems in the world. From the consistent thunder of equatorial torrents to the dusty beds of desert wadis, each river has a rhythm shaped by rainfall, topography, and time.

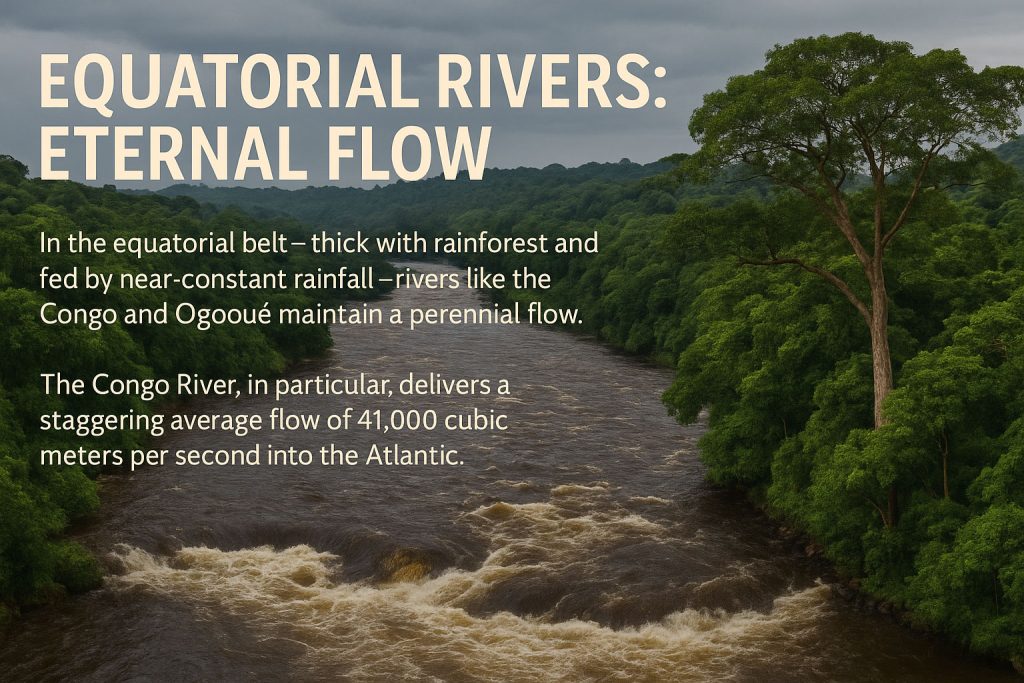

Equatorial Rivers: Eternal Flow

In the equatorial belt—thick with rainforest and fed by near-constant rainfall—rivers like the Congo and Ogooué maintain a perennial flow. These are vast arteries of water that rarely falter, fueled by humid air masses and dense vegetation that traps and releases moisture evenly across the year.

The Congo River, in particular, has the most stable discharge in Africa, delivering a staggering average flow of 41,000 cubic meters per second into the Atlantic. It never truly dries, never truly floods. It simply pulses, like a colossal, ancient heart.

Savannah and Sahel Rivers: The Breath of Seasons

In contrast, rivers in the savannah and Sahel zones—such as the Niger, Senegal, and Benue Rivers—are seasonal in temperament. Their flow is heavily governed by the West African Monsoon, bringing intense rains between June and September, followed by dry months where water levels shrink dramatically.

These rivers expand into vast floodplains—like the Inner Niger Delta in Mali—creating rich ecosystems and traditional agricultural calendars where communities plant as the waters recede. But this rhythm is fragile: late rains, shorter wet seasons, or prolonged droughts can upend life for millions.

Desert Rivers: Ghost Streams from Distant Rains

In Africa’s arid north, rivers such as the Nile in Egypt, the Draa in Morocco, or the Awash in Ethiopia, flow through deserts but not from them. They depend on rainfall from highland regions hundreds or thousands of kilometers away, funneled down narrow valleys to places that may not have seen rain for years.

The Nile, for instance, flows through some of the driest land on Earth, yet persists because of its highland sources: the Blue Nile from Ethiopia and the White Nile from the equatorial lakes. Its flow is so reliant on distant rains that Ethiopian monsoon cycles can determine agricultural success or failure in Egypt.

Ephemeral and Intermittent Rivers: Fleeting Waters

Across the semi-arid zones and deserts, many rivers are ephemeral—visible only during and after heavy rain. Known locally as wadis in North Africa or arroyos in the Sahel, these channels may be bone-dry most of the year but can erupt in flash floods powerful enough to reshape the landscape overnight.

Even more intermittent rivers, like parts of the Limpopo, Tugela, or the Seasonal tributaries of the Niger, flow only a few weeks per year. Yet, their brief existence is vital: recharging aquifers, enabling short bursts of farming, and creating temporary aquatic habitats.

Explore ephemeral and intermittent rivers in greater detail.

The Role of Climate Variability

At the heart of Africa’s hydrology lies climate variability. Shifts in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) determine where and when rain falls. In El Niño years, rainfall patterns can flip—droughts in Southern Africa, floods in East Africa. Climate change amplifies this unpredictability, disrupting ancient rhythms.

Hydrological extremes are now becoming more common: longer droughts, more violent floods, and shifting wet seasons. Rivers once considered dependable are behaving differently—challenging water managers, farmers, and entire nations.

In Africa, a river is never just a river. It is memory, risk, hope, and survival. Its flow may be steady or sporadic, but always it carries with it the story of the land and sky from which it came.

Sculptors of the Land: River Morphology in Africa

African rivers are not just carriers of water—they are sculptors, etching their stories into the land over millennia. Along their journey from mountain spring to ocean mouth, they carve, flood, meander, and deposit, giving rise to some of the most iconic and varied riverine landscapes on Earth.

Deltas: Green Fans at the End of the Journey

Where a river meets the sea and loses its energy, it spreads out like a fan, depositing rich sediment and forming a delta. Africa is home to some of the most ecologically important and culturally iconic deltas. The Niger Delta, a maze of swamps, creeks, and mangroves, is one of the largest in the world and vital for West African biodiversity. Discover more about river deltas.

Meanwhile, the Okavango Delta in Botswana is a geological marvel—an inland delta where the river never reaches the sea. Instead, it evaporates into the sands of the Kalahari, creating a lush seasonal paradise that sustains elephants, lions, hippos, and countless birds.

Estuaries: Where Salt and Fresh Waters Embrace

In regions where rivers meet the sea more directly, estuaries form—brackish water zones that serve as nurseries for fish and birds. The Limpopo River estuary in Mozambique and the Incomati estuary are vital ecological transition zones. Here, tidal flows and river currents dance together, creating complex habitats of reeds, mudflats, and mangrove forests—ecosystems rich in productivity and delicate in balance.

Canyons and Gorges: Rivers as Chisels

The powerful force of water, grinding rock over time, has carved some of the most dramatic canyons and gorges in Africa. The Batoka Gorge, downstream from Victoria Falls on the Zambezi River, slices deep through basalt cliffs, creating thrilling rapids and breathtaking views. In Ethiopia, the Blue Nile Gorge plunges deeper than the Grand Canyon, winding through the highlands like a massive geological scar. These features are reminders of rivers’ sheer power to cut through even the hardest stone, given time and tenacity.

Valleys and Floodplains: Cradles of Life

Along more gentle stretches, rivers widen and slow, creating valleys and floodplains—some of Africa’s most fertile and historically significant regions. The Nile Valley, a green ribbon through the sands of Egypt and Sudan, is a striking example of how a river can create an oasis in the desert. In East Africa, the Rufiji River floodplain in Tanzania supports rice farming, wetlands, and a rich array of wildlife. These seasonal flood zones are often the birthplaces of agricultural traditions, where the cycle of rising and receding waters dictates the rhythm of human life.

Meanders, Oxbows, and Braided Channels: Rivers on the Move

Many African rivers, especially in low-lying regions, exhibit winding meanders, constantly reshaping their paths. Over time, these curves can be cut off to form oxbow lakes, like those seen along the Congo River. In fast-draining floodplains, rivers like the White Nile in South Sudan can become braided, splitting into multiple intertwining channels—each one changing with each rainy season, like a living mosaic of water and land.

These landforms are more than scenery—they are habitats, borders, migration paths, and lifelines. Each bend, fork, and mouth tells a geologic story that connects climate, soil, plant life, animals, and people. To understand Africa’s rivers is to read the land as a living map—constantly being redrawn by water.

🌿 Ecology and Biodiversity

Lifelines for Wildlife and People

Africa’s rivers are not just bodies of water—they are living ecosystems, breathing corridors that connect forests to plains, deserts to seas, and species to survival. Each river tells a different ecological story, but all are bound by a shared rhythm of life, shaped by the flood pulse, seasonal flow, and surrounding habitat. These rivers nourish some of the most extraordinary biodiversity on Earth.

The Congo Basin: The Emerald Labyrinth

At the heart of Central Africa lies the Congo River Basin, a vast, tangled expanse of rainforest, swamp, and river channels. It is the second-largest tropical rainforest in the world, after the Amazon, and a cradle of evolution.

Within its floodplains and dark waters roam forest elephants, bonobos (a close relative of humans), elusive okapis, and dozens of amphibian and fish species found nowhere else. Some tributaries contain hypoxic waters—low in oxygen—yet adapted fish species thrive here, evolved over millennia to breathe in near-alien conditions.

The Niger Delta: A Mosaic of Life and Mud

Where the Niger River fans out into the Atlantic, it creates one of the largest and most complex wetland ecosystems in Africa. Its tangled mangrove forests, creeks, and swamps teem with life.

The delta is a sanctuary for West African manatees, crocodiles, mudskippers, and countless migratory birds that arrive from Europe and Asia. These wetlands act as nurseries for fish and crustaceans, while also providing food and materials for millions of people who depend on fishing, farming, and gathering from its fertile margins.

The Okavango Delta: A Miracle in the Sand

The Okavango Delta in Botswana is one of the world’s most fascinating anomalies—an inland delta with no outlet to the sea. Here, water from Angola’s highlands pours into the Kalahari Desert, creating a shifting paradise of lagoons, floodplains, and islands.

Each year, the flood arrives during the dry season, a miraculous reversal of expectation. Wildlife congregates: elephants bathe, lions hunt buffalo in the reeds, leopards stalk lechwe, and hundreds of bird species nest and feed. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most celebrated wildlife destinations on the planet.

The Zambezi River: Predator and Prey

The Zambezi River, powerful and unpredictable, slices through diverse terrains—its waters brimming with hippos, Nile crocodiles, and tigerfish, one of Africa’s fiercest freshwater predators. It supports wetland birds, from saddle-billed storks to African jacanas, and sustains vast reedbeds and riparian forests along its banks.

The seasonal floodplains, especially in places like the Barotse Floodplain in Zambia or the Caprivi Strip, are home to grazing antelope, buffalo, and predators that follow them.

🦓 The Mara River: Nature’s Most Dramatic Crossing

Few river events on Earth compare to the Great Wildebeest Migration across the Mara River, straddling Kenya’s Masai Mara and Tanzania’s Serengeti. Each year, over 1.5 million wildebeest, accompanied by zebras and gazelles, thunder across the savannah in a primal search for fresh grass and water.

Their journey leads them to the Mara River, a deceptively tranquil waterway that becomes the setting for one of the most dramatic wildlife spectacles on the planet. As herds mass at the riverbanks, tension builds. They hesitate. They surge. They leap.

In the swirling current below, Nile crocodiles—some over five meters long—lie in wait. The crossing becomes a deadly chaos of splashing hooves, snapping jaws, and instinct.

But beyond the drama, the Mara River is a lifeline. It supports year-round wildlife in the Mara-Serengeti ecosystem, nourishing acacia groves, sustaining grazing lands, and helping maintain one of Africa’s last truly wild landscapes. The health of this river—now threatened by deforestation and overgrazing upstream—is essential not only for biodiversity, but for one of Earth’s most iconic natural rhythms.

🏞️ More Than Wildlife: Rivers Shape Habitats

Africa’s rivers don’t just support animals—they create entire landscapes. Floodplains, gallery forests, seasonal wetlands, and alluvial grasslands arise around them, forming mosaic habitats where life flourishes. These zones are often the most productive ecosystems, vital for:

- Grazing animals like antelope and zebras.

- Small-scale agriculture on rich, sediment-fed soils.

- Fishing communities, harvesting both fish and aquatic plants.

They are stepping stones for migratory species, especially birds, that follow the rivers from breeding grounds to overwintering sites.

🐟 A Hidden Treasure: Endemic Freshwater Life

Africa’s rivers also host remarkable aquatic life. Many fish species are endemic, meaning they exist nowhere else on Earth. For example:

- The Upper Congo holds over 700 species of fish, with many still undescribed by science.

- The Lake Turkana River system in Kenya contains ancient cichlids adapted to extreme conditions.

- The Rufiji and Ruaha Rivers in Tanzania support endangered killifish and freshwater prawns vital to local food chains.

Some species have evolved in isolation, separated by waterfalls, rapids, or deep channels for tens of thousands of years.

In every ripple, bend, and seasonal surge, Africa’s rivers breathe life into the continent. They are more than watercourses—they are cradles of creation, refuges of survival, and the roots of ecological resilience. To protect these rivers is to protect the pulse of Africa itself.

🏛️ The Role in Human Civilization

Rivers as Cradles of Culture, Power, and Memory

Long before maps and empires, before the rise of cities or the carving of stone, there was the river—the first road, the first lifeline. In Africa, rivers were not merely geographical features; they were the birthplaces of civilization, the veins of trade, and the channels of belief.

The Nile: Mother of Empires

Perhaps no river has shaped human history as profoundly as the Nile. Stretching through the arid deserts of North Africa, the Nile brought life to Egypt long before the pyramids rose from the sand. Its predictable annual flooding laid down a rich layer of silt, transforming a narrow valley into a fertile ribbon of agriculture amid the desert.

The rhythm of the Nile governed ancient calendars, crop cycles, and festivals. It was worshipped as a deity, charted by priests, and sailed by pharaohs. Every aspect of Ancient Egyptian civilization—writing, religion, architecture, trade—was rooted in the reliable pulse of this river.

The Niger River: Highway of the Sahel

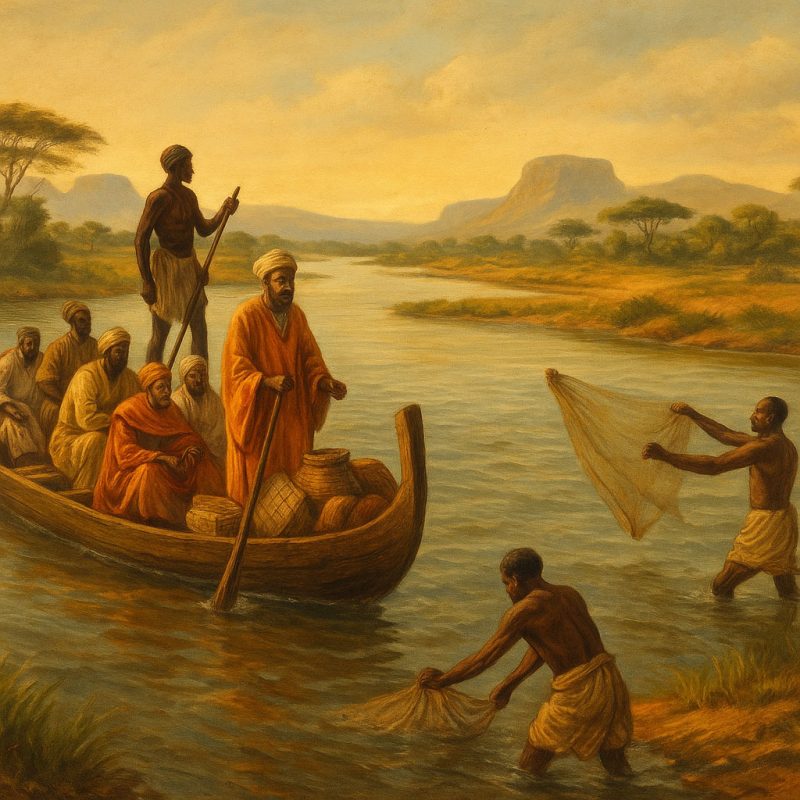

Thousands of kilometers to the west, the Niger River carved a great arc through the Sahel, shaping the Mali and Songhai Empires, two of the most influential West African powers of the medieval era. The river’s inland delta became a natural engine of commerce, a fertile floodplain that allowed rice cultivation, fishing, and pastoralism to flourish.

Cities like Timbuktu and Djenné rose along its banks—centers of Islamic learning, manuscript libraries, and trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and slaves. The Niger was a cultural corridor, connecting caravan routes with river ports and helping ideas, goods, and peoples move across a challenging, semi-arid landscape.

Rivers as Trade Routes and Sacred Corridors

Beyond agriculture, rivers acted as natural highways long before roads or railways. Traders traveled the Congo River deep into Central Africa’s interior. Fishermen cast nets along the Senegal and Gambia Rivers, while the Zambezi provided passage into mineral-rich southern regions.

But rivers were not only used—they were revered. In many African societies, rivers are believed to harbor spirits, serve as gateways to the ancestors, or represent boundaries between worlds. Water rituals, fertility ceremonies, and funerary rites often revolve around rivers. From the animist traditions of the rainforest to the Sufi poetry of the Nile, rivers are woven into the very soul of African spirituality.

Language, Myth, and Memory

Across Africa, languages bear the echo of rivers. Words for “life,” “blood,” and “river” often share the same root. Myths speak of river gods and hidden waters, of creatures who guard the currents and stories that unfold only in the flood season.

These are not merely metaphors. They are reflections of how deeply embedded rivers are in the collective memory of African civilizations. They shaped settlement patterns, dictated seasonal movements, and even inspired the layout of kingdoms and cities.

In the African context, rivers were not obstacles to be overcome—they were the original architecture of society, the threads that bound environment and identity, both sacred and practical. To understand the human history of Africa, one must follow the rivers—where every bend tells a story.

⚓ Economic Importance: Navigation, Hydropower, Agriculture

Rivers as Engines of Livelihood and Growth

Africa’s rivers are not only the beating heart of ecosystems—they are also the economic arteries that sustain communities, feed populations, power cities, and link regions across the vast and varied continent. Their economic value lies not only in what flows through them, but in how they shape the land, the infrastructure, and the possibilities for the future.

🌾 Agriculture: Sowing in the Shadow of the River

For thousands of years, African farmers have depended on flood cycles to enrich their fields with nutrient-rich silt and water. The floodplains of rivers like the Nile, Niger, Senegal, and Zambezi remain vital agricultural zones where the land becomes naturally irrigated and fertile after seasonal inundation.

- In Egypt, the Nile Valley supports millions of people and forms the green core of an otherwise arid country. Its ancient irrigation systems have evolved into vast modern networks feeding crops of wheat, sugarcane, and vegetables.

- In the Senegal River Valley, transboundary water cooperation between Senegal, Mali, and Mauritania has enabled dryland farming and grazing, even in the face of growing climate stress.

- Across East and Southern Africa, rivers support rice paddies, maize fields, banana groves, and more, often with small-scale irrigation schemes managed by communities.

But this lifeline is under pressure. Changes in rainfall, upstream damming, and population growth strain the balance between water supply and food security.

⚡ Hydropower: Energy from the Flow

Africa’s rivers hold enormous hydroelectric potential, especially in the Congo Basin, Ethiopian Highlands, and Southern Africa. Several large dams already contribute to national grids—and even regional energy exports:

- The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile is Africa’s largest hydroelectric project. It promises to bring power to tens of millions but has also triggered international tensions with Egypt and Sudan over water rights and seasonal flow.

- The Inga Dams on the Congo River tap one of the world’s most powerful river systems, with plans for a massive expansion—Inga III—which could theoretically power much of sub-Saharan Africa. However, the project faces political, financial, and environmental hurdles.

- Kariba Dam (Zambia/Zimbabwe) and Cahora Bassa (Mozambique) harness the mighty Zambezi, generating electricity for national and cross-border use—but also altering river ecology and affecting downstream communities and wetlands.

While hydropower offers a low-carbon energy solution, it is not without cost. River fragmentation, fish migration disruption, and floodplain drying are some of the serious environmental consequences—especially when dams are built without thorough social and ecological planning.

🚢 Navigation and Transport: Rivers as Highways

Though many African rivers are broken by waterfalls and rapids, they still function as natural transport corridors, particularly in regions where roads are scarce or seasonal.

- The Congo River is a lifeline in Central Africa, enabling trade and movement deep into otherwise inaccessible rainforest regions. Barges and pirogues ferry goods and passengers between river towns in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, from Kisangani to Kinshasa.

- In West Africa, the Niger River supports both local fishing canoes and larger vessels carrying rice, millet, salt, and livestock to bustling markets.

- Along the Zambezi, ferries and boats link riverine communities and mining regions, even though navigation is seasonal and often disrupted by shifting sandbank.

For many remote communities, rivers are still the most reliable mode of transport, connecting isolated villages to schools, health clinics, and markets.

Rivers in Africa are more than just sources of water—they are sources of life and labor, productivity and power. Their value is measured not only in kilowatts or harvests, but in resilience: the ability of millions of people to grow food, earn income, and build a future in a changing climate.

⚠️ Threats to African Rivers

Despite their strength, Africa’s rivers are under siege:

1. Dams and Water Diversion

Block migration routes, disrupt flood cycles, affect downstream ecosystems.

2. Climate Change

Unpredictable rainfall, prolonged droughts, and extreme floods destabilize flows.

3. Pollution

Urban runoff, industrial waste, oil spills (e.g., Niger Delta), and untreated sewage degrade water quality.

4. Deforestation & Erosion

Clearing of forests along riverbanks leads to siltation and loss of biodiversity.

5. Overuse & Mismanagement

Poor water governance, over-extraction for farming, and unchecked development put both rivers and dependent communities at risk.

🧭 Final Reflection

Africa’s rivers are far more than blue lines on a map.

They are moving stories, shaping everything they touch—from the soil beneath your feet to the myths in your grandmother’s voice.

To protect them is to protect life, heritage, and the future of a continent.