Rivers of the United States: The Lifelines of a Continent

Explore the rivers of the United States—hydrology, major basins, ecology, people, and conservation threats shaping America’s most vital waterway

From the icy headwaters of the Rockies to the winding bayous of the Deep South, rivers are the pulse of the North American landscape. They carve canyons, nourish cities, flood plains, whisper through forests, and roar across deserts. Rivers of the United States are not just waterways—they are histories in motion, natural highways, cultural borders, and wild sanctuaries. Let’s journey from source to sea and explore the great veins that flow through the heart of this vast continent.

Geography & Geology

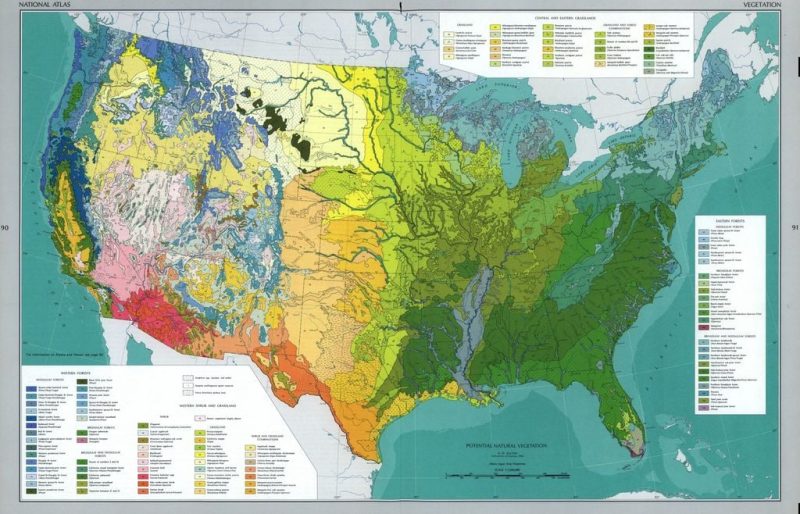

The rivers of the United States are not randomly scattered threads but a vast, interconnected web—woven by the hands of tectonics, climate, erosion, and time. Their paths trace the history of uplifted mountains, fractured bedrock, and shifting sea levels, revealing not just the shape of the land, but the very processes that built the continent itself.

From the rugged peaks of the Rockies to the ancient worn-down Appalachians, rivers have followed the lines of least resistance, carving valleys and gorges as they go. The steep gradients of young mountainous terrain give rise to fast-flowing, straight-cut rivers, while older, more stable regions invite meandering flows that twist like serpents through wide plains and lowlands.

Beneath the surface, geology defines every turn and fall. Hard igneous rocks resist erosion, forming waterfalls and rapids, while softer sedimentary layers allow rivers to dig deep canyons, like the Colorado slicing through eons of rock. In limestone regions, water disappears underground, forming vast cave systems before reemerging as springs. Along coastal plains, ancient seabeds now host slow, silt-laden rivers that drift lazily toward the sea.

Glaciers also played their part. During the last Ice Age, massive ice sheets gouged out basins, rerouted ancient rivers, and left behind kettle lakes and braided streams. Much of the modern river geography in the northern U.S.—from Minnesota’s lake-studded terrain to New England’s drowned river mouths—owes its existence to the icy hand of glaciation.

In short, to study the geography and geology of American rivers is to read the Earth’s autobiography: a layered tale of upheaval, flow, and transformation written in stone and water.

🗺 Major Drainage Basins and Catchments

The rivers of the United States form five monumental drainage systems, each one a continent-spanning circulatory network collecting water from thousands of tributaries and feeding the pulse of life into distant oceans and gulfs.

The Mississippi River Basin – The Nation’s Liquid Spine

The Mississippi River Basin is the titan of them all. Draining over 40% of the continental U.S., it spans from the crest of the Rockies in the west to the ridges of the Appalachians in the east. It’s not just a river—it’s a nation within a nation, with the Missouri and Ohio Rivers as powerful veins, funneling rain and snowmelt into the lower Mississippi’s slow, meandering journey to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Colorado River Basin – Lifeline of the Arid Southwest

The Colorado River Basin is the pulse of the American Southwest. Sourced in the snow-laden peaks of the Rockies, this river has carved its way through sandstone temples and desert silence, etching the Grand Canyon itself into existence. Its waters are precious, divided between states and nations, sustaining agriculture and cities alike—though today, its lower reaches often run dry before reaching the sea.

The Columbia River Basin – Power and Wildness of the Northwest

The Columbia River Basin, born in the glaciated peaks of the Rockies and Cascades, surges westward toward the Pacific. This powerful system, along with its mighty tributary the Snake River, carries cold mountain water through basalt gorges, generating immense hydroelectric power and supporting rich fisheries—especially for salmon.

The Rio Grande Basin – A River of Boundaries

The Rio Grande Basin flows quietly but profoundly along the seam of nations. Rising in the Colorado Rockies and descending through New Mexico and Texas, it threads through high deserts and dry valleys, forming a natural border between the U.S. and Mexico. Here, scarcity defines the landscape, and every drop is a contested resource.

The Great Lakes–St. Lawrence System – North America’s Freshwater Highway

The Great Lakes–St. Lawrence System is a freshwater colossus. Born of ancient glacial lakes, these interconnected inland seas drain eastward into the Atlantic via the St. Lawrence River. This system is not only a critical shipping corridor but a vital ecological link between forested heartlands and coastal estuaries, hosting one of the largest bodies of freshwater on Earth.

Together, these drainage basins define not just where the water flows—but how civilizations rise, how ecosystems breathe, and how landscapes are continually rewritten.

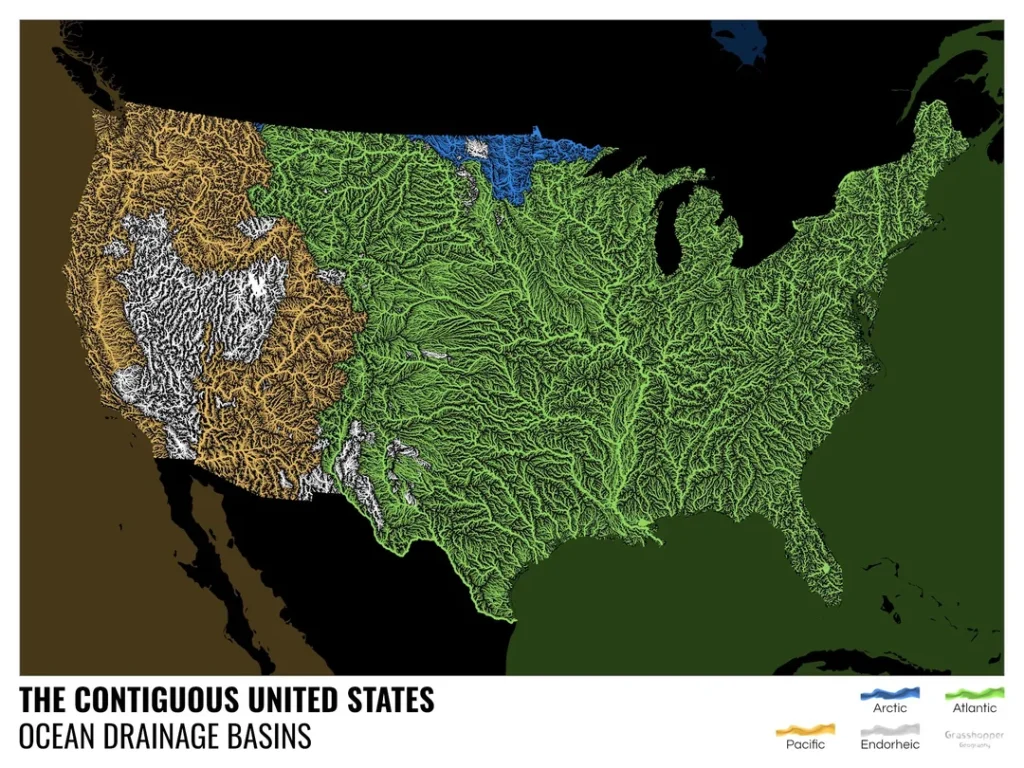

🌊 Drainage into the Seas: Where America’s Rivers End

While rivers begin in the quiet solitude of springs, snowfields, or mountain lakes, they all flow toward something larger. In the United States, every river belongs to one of four major drainage destinations—each a watery threshold between land and sea, or sometimes, land and sky.

Pacific Ocean – Where Mountains Rush to the Sea

Rivers flowing westward from the Sierra Nevada, Cascades, and western Rockies descend steeply toward the Pacific. The Columbia, Sacramento, San Joaquin, and Klamath rivers charge through canyons and valleys before reaching the ocean. These rivers are relatively short but mighty, shaped by tectonic uplift and volcanic terrain. Many are heavily dammed, yet still support agriculture, power, and some of the wildest landscapes in the American West.

Atlantic Ocean – Cradle of Cities and Trade

On the eastern side of the continent, rivers like the Hudson, Delaware, Potomac, and Savannah gently flow toward the Atlantic. Rising in the Appalachians and coastal highlands, these rivers were central to the growth of early American colonies. Today, they continue to feed estuaries and bays that teem with life, shaping harbors, salt marshes, and urban skylines from New England to the Carolinas.

Gulf of Mexico – The Sediment-Rich South

Although part of the Atlantic drainage, the Gulf of Mexico deserves special mention. It receives the outpouring of the Mississippi River, the Rio Grande, and dozens of smaller southern rivers. These rivers carry the soils of America—topsoil from farms, silt from floodplains, and runoff from thousands of tributaries—building vast deltas and wetlands like the Mississippi Delta and Atchafalaya Basin. These are zones of life, complexity, and increasing vulnerability.

Arctic Ocean – Where Ice Feeds the Flow

In the far north, the Yukon River and other Alaskan waterways journey toward the Arctic Ocean, through landscapes defined by permafrost, boreal forest, and tundra. These rivers are wild and remote, supporting Indigenous communities, caribou migrations, and seasonal salmon runs. Their icy pulses are deeply tied to the rhythms of melting glaciers and shrinking sea ice.

Endorheic Basins – The Rivers That Never Reach the Sea

Not all American rivers meet the ocean. In the Great Basin of the West, rivers like the Humboldt flow into closed basins where water evaporates or seeps into salt flats. These endorheic systems are hauntingly beautiful—home to ancient lakebeds, brine pools, and ghostly mirages. In these basins, water does not complete a journey to the sea, but instead vanishes into desert silence.

Each of these drainage paths tells a different story—of altitude and gravity, of climate and contour, of use and neglect. Where a river ends is not the end of its story—but the beginning of something else: a delta, a bay, a marsh, or a memory.

💧 Hydrology

The hydrology of the rivers of the United States is as diverse as the landscapes they traverse—ranging from glacial torrents roaring down alpine slopes to sluggish blackwater streams creeping through subtropical swamps. This diversity is driven by geography, geology, and climate, creating distinct water regimes across the continent.

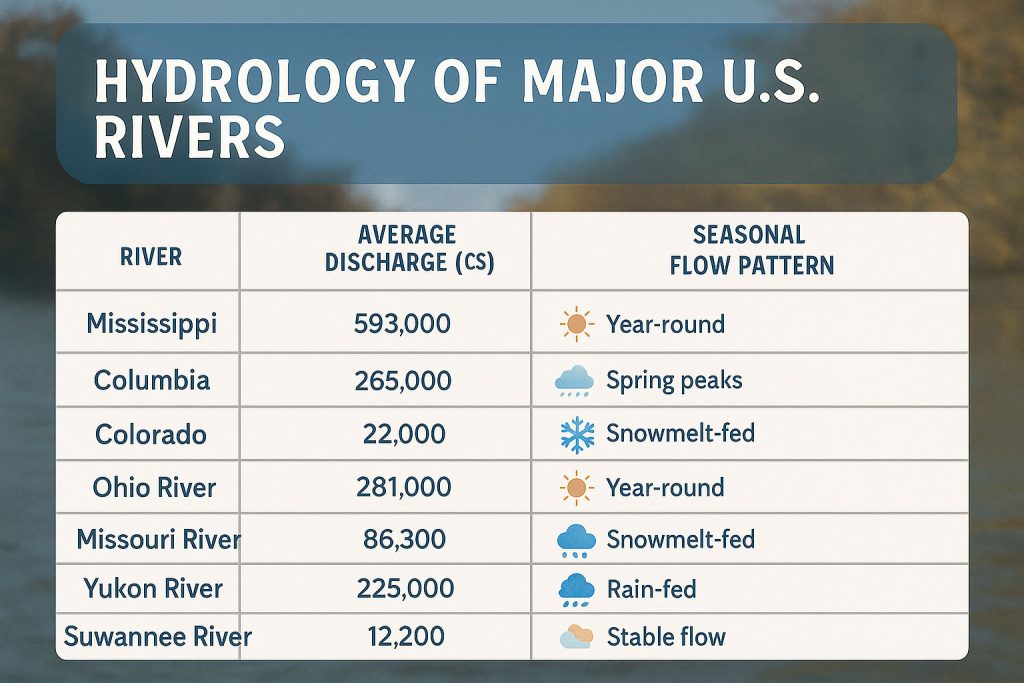

Flow Regimes: Rhythms of Rise and Fall

Every river has a unique flow regime—its natural rhythm of discharge, which can range from consistent year-round flows to dramatic seasonal pulses. In mountainous regions like the Rockies and Sierra Nevada, rivers such as the Columbia, Missouri, and Colorado are fed primarily by snowmelt. These rivers rise in late spring and early summer, peaking as temperatures thaw alpine snowpacks. The Columbia River, for instance, averages a mean annual discharge of 265,000 cubic feet per second (cfs)—one of the highest in North America.

In contrast, Appalachian rivers like the Potomac, James, and Tennessee tend to be rainfall-driven, with more variable year-round flow and frequent winter and spring floods. The Tennessee River discharges about 70,000 cfs, but its flow is heavily managed through a series of TVA dams.

In the humid Southeast, rivers like the Suwannee, Altamaha, and Pascagoula begin in lowland wetlands and exhibit stable, meandering flows through cypress forests and coastal plains. These blackwater rivers are often acidic, rich in tannins, and biologically unique.

Meanwhile, in the arid Southwest, rivers like the Gila, Santa Cruz, and lower Rio Grande are ephemeral—flowing only seasonally or after rainstorms. The Colorado River once surged with over 22,000 cfs at its mouth, but today, due to over-extraction and dams, it frequently fails to reach the sea.

Discharge and Scale: From Trickle to Torrent

The Mississippi River, America’s hydrological giant, has a mean annual discharge of 593,000 cfs at its mouth, making it the fourth-largest in the world by volume. It carries a staggering 16,792 cubic meters per second, draining 31 U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. By comparison, smaller rivers like the Humboldt in Nevada or Santa Ana in California have much lower flow, often dipping below 100 cfs during dry spells.

Some rivers display braided channels, like the Platte River, due to high sediment loads and fluctuating discharge. Others, like the Hudson, are tidal for much of their course, with flow reversing twice daily under the influence of ocean tides.

Groundwater and Springs: The Hidden River Beneath

Not all flow is visible. Many U.S. rivers are fed by aquifers, such as Florida’s Karst springs, which give rise to crystal-clear rivers like the Ichetucknee and Silver River. These spring-fed rivers have near-constant temperature and flow, supporting endemic wildlife and recreational use year-round.

River Ecology: From High Mountains to Desert

The ecological journey of an American river is like traveling through a continent in miniature—from alpine tundra and forested valleys to sun-baked canyons and brackish estuaries. Each stretch of a river tells a story of adaptation, migration, and interdependence, shaping not only landscapes but also the lives that flow with it.

🏔 Headwaters: Life in the Mountains

Rivers often begin in the snowfields and glacial lakes of high mountain ranges like the Rockies, Sierra Nevada, or Cascades. Here, the water is icy cold, swift, and saturated with oxygen—the perfect environment for species that thrive in clean, turbulent flow.

- Trout, salmon, and sculpin navigate rock-strewn channels.

- Mosses, algae, and lichens cling to submerged stones, forming the base of the food chain.

- Insects like stoneflies and caddisflies hatch seasonally, feeding birds and amphibians.

These headwaters are fragile ecosystems, highly sensitive to changes in snowpack, temperature, and pollution. Even slight warming or sedimentation can disrupt these specialized communities.

🌲 Forest Valleys and Mid-Elevation Slopes

As rivers descend, they gather strength from tributaries and begin to widen and meander through forested landscapes and foothills. The gradient softens, and the ecology shifts with the tempo of the water.

- Beavers become ecosystem engineers, damming streams to create wetland mosaics.

- River otters, herons, and kingfishers hunt along the riverbanks.

- Willows, alders, and cottonwoods shade the water, stabilizing soil and dropping leaves that feed aquatic invertebrates.

These stretches are vital for nutrient cycling and biodiversity. They support a broader range of species while buffering communities from flooding and drought.

🌾 Plains and Floodplains: Rivers That Feed the Land

In the Midwest and Deep South, rivers slow into braided channels and oxbow lakes, surrounded by lush floodplains. Here, seasonal floods enrich the soil and sustain a vibrant mix of terrestrial and aquatic life.

- Turtles, frogs, and salamanders thrive in still backwaters.

- Egrets, cranes, and ducks depend on the wetlands for nesting and feeding.

- Fish like catfish, bass, and gar navigate slow currents and vegetated margins.

These floodplains are America’s biological breadbaskets, but also among its most endangered habitats due to levees, agriculture, and development.

🏜 Desert Rivers: The Pulse of the Arid Southwest

In the desert regions of the Southwest, rivers like the Santa Cruz, Gila, and Rio Grande often flow only seasonally or intermittently, responding to rains and snowmelt.

- Their dry beds, known as arroyos or washes, become lifelines during monsoons, reviving cottonwoods, willows, and even endangered fish.

- Wildlife like jackrabbits, roadrunners, and coyotes rely on the brief bloom of life around these rivers.

- Insects emerge en masse, feeding bats and swallows in explosive ecological events.

These rivers demonstrate extreme ecological resilience, adapting to scarcity with pulses of abundance.

🌊 Estuaries and Deltas: Where Freshwater Meets the Sea

At their journey’s end, rivers enter the most biologically productive ecosystems on Earth—estuaries and deltas. These brackish zones are not just rich in life, but also in carbon storage and storm protection.

- The Chesapeake Bay, Mississippi Delta, and San Francisco Bay are key nurseries for shrimp, oysters, crabs, and juvenile fish.

- Mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrasses trap sediment, buffer coastlines, and capture carbon.

- Birds like pelicans, egrets, and migratory shorebirds depend on these zones during critical phases of their life cycles.

But these vital habitats are increasingly threatened by sea level rise, pollution, and wetland loss.

🌎 River Corridors as Ecological Highways

Beyond each section’s unique traits, rivers act as connective tissue between biomes. Migratory birds follow river flyways, fish move upstream to spawn, and seeds drift with the current to colonize new ground.

In essence, rivers are not just habitats, but pathways of life—a dynamic thread binding mountains to oceans, deserts to wetlands, and past to future.

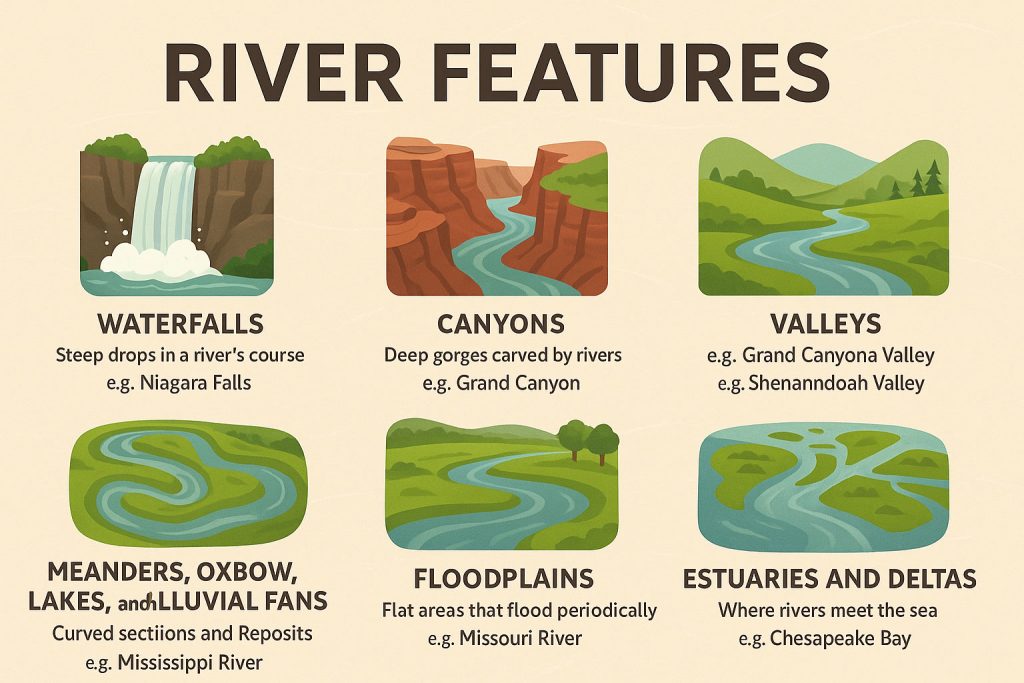

River Features: Sculptors of the American Landscape

Rivers are Earth’s patient sculptors—shaping canyons, spreading floodplains, and painting coastlines not with tools, but with time, sediment, and persistence. Across the United States, from the rugged Rockies to the drowned Atlantic shores, rivers have carved and constructed some of the country’s most iconic features.

🏞 Canyons and Gorges: Deep Stories in Stone

In the West, rivers like the Colorado have carved epic canyons through rock that’s hundreds of millions of years old. The Grand Canyon, one of Earth’s most awe-inspiring landscapes, was sculpted over 5–6 million years by the Colorado River cutting through uplifted plateau and layered sandstone, limestone, and shale.

The Snake River, too, has chiseled out Hell’s Canyon—deeper than the Grand Canyon, with sheer basalt cliffs plunging into a wild gorge system. These deep incisions reveal Earth’s tectonic past and the relentless downward cutting of rivers through rising land.

🌄 Valleys and River Corridors: Cradles of Life and Culture

Rivers such as the Connecticut, Hudson, and Tennessee have carved broad valleys that became settlement corridors, farming basins, and transportation routes. The Appalachian rivers, while lacking the drama of Western gorges, are quietly powerful—carving gentle slopes and fertile troughs that gave rise to early American towns and trade.

The Willamette Valley in Oregon, formed by glacial flooding and river erosion, is a prime example of a river-shaped agricultural heartland. The river valleys of the Midwest—like the Illinois and Wabash Rivers—remain vital ecological and economic arteries.

🌀 Meanders, Oxbows, and Alluvial Fans: The Art of the Slow Curve

As rivers age and the landscape flattens, they slow down and begin to wander. The Mississippi River, one of the most meandering rivers in the world, has created countless oxbow lakes and sweeping meander scars across its vast floodplain.

These gentle arcs are visible from space—reminders of how rivers constantly rewrite their course. Further west, where high mountain streams fan out onto arid basins, rivers like the Kern and Cache la Poudre create alluvial fans—broad spreads of rock, gravel, and sand, perfect for farming when water is present.

🌾 Floodplains: Rivers That Feed the Earth

Floodplains are the breathing lungs of rivers. In the Midwest and Deep South, rivers like the Missouri, Ohio, and Arkansas seasonally overflow, spreading nutrient-rich silt across vast bottomlands. These floods are not disasters—they’re renewals.

The Lower Mississippi River floodplain once supported one of the world’s richest wetland systems, before levees and development reduced its reach. Smaller rivers like the Red River of the South or the Alabama River still nourish intact floodplain forests teeming with amphibians, reptiles, and migratory birds.

💧 Waterfalls: Rivers in Freefall

Where rivers leap off cliffs, they reveal another sculpting power—vertical erosion and bedrock collapse. The Niagara River, connecting Lakes Erie and Ontario, has retreated over 11 kilometers since its formation, forming the thunderous Niagara Falls, one of the most iconic waterfalls on Earth.

In the Pacific Northwest, Multnomah Falls, fed by a tributary of the Columbia, plunges through moss-draped cliffs—a cascade formed by lava flows and glacial scouring. In the Appalachians, waterfalls like Amicalola, Fall Creek Falls, and Cumberland Falls hint at ancient geologic fractures and layers of sandstone laid down long before the first settlers arrived.

🧭 Deltas: Where Rivers Build New Land

At their mouths, rivers slow down and release the burden of sediment they’ve carried for hundreds of miles. The Mississippi River Delta, fanning into the Gulf of Mexico, is a vast, shifting landscape of bayous, marshes, and freshwater lakes.

Smaller but equally dynamic deltas form where the Sacramento–San Joaquin River system enters California’s Central Valley, or where the Yukon River meets the Bering Sea. These are living landforms, expanding and shrinking with tides, storms, and the sediment balance.

🌊 Estuaries: Where Freshwater Meets the Sea

Estuaries are brackish crossroads—where river and ocean meet, mix, and nourish life. The Chesapeake Bay, fed by the Susquehanna and Potomac Rivers, is North America’s largest estuary, supporting crabs, oysters, striped bass, and vast underwater grasses.

The Columbia River Estuary, on the Pacific coast, mixes glacial runoff with salty currents, forming vital nurseries for salmon and other fish. These environments are ecological filters and storm buffers, absorbing energy and trapping nutrients before they reach open water.

🌍 A Living Sculpture

Rivers sculpt not only rock and earth, but histories and futures. They carve deeply, deposit gently, fall violently, and flow rhythmically. They create features we live beside, marvel at, farm within, and fight to protect.

From the shadowed gorges of the West to the glittering deltas of the Gulf, American rivers are landscape artists in motion—etching meaning and memory into the very fabric of the land.

People Along the Riverbanks

From the ancient mound builders of the Mississippi to modern metropolises like New York (Hudson River), Washington D.C. (Potomac), and Portland (Willamette), rivers have always drawn people to their banks. Indigenous nations thrived along them—the Lenape on the Delaware, the Chinook on the Columbia, the Anishinaabe by the Great Lakes—hunting, fishing, trading, and praying to the waters.

Colonial powers followed rivers inland. Pioneers used them as roads. Cities were born at confluences. Today, rivers still provide drinking water, recreation, and spiritual connection—but they also bear the burden of agriculture, industry, and overuse.

Threats and Conservation Challenges

The American river story is also one of loss and struggle. More than 75,000 dams crisscross the U.S., altering flow, blocking fish migrations, and drowning ecosystems. Agricultural runoff creates dead zones in places like the Gulf of Mexico. Urban sprawl pollutes, straightens, and silences formerly wild stretches.

Climate change brings new pressures—longer droughts in the West, stronger floods in the East, and rising seas that salt marshes and estuaries. Iconic rivers like the Colorado no longer reach the sea. Yet, hope flows too: dam removals on rivers like the Elwha and Klamath are reviving salmon runs. Grassroots groups are rewilding banks. Tribal nations are leading restorations of their sacred waters.

Conclusion: Rivers as Memory and Motion

To follow a river is to read a continent. It’s to witness change—geological, ecological, cultural. American rivers are archives of ice and fire, migration and resilience, industry and renewal. They are mirrors of the past and currents of the future.

So next time you stand at the edge of a river—be it the mighty Mississippi or a forest brook in Vermont—listen. The water is telling stories, ancient and urgent, local and continental. Let’s keep them flowing.