How fast are rivers?

From gentle drifts to roaring torrents, rivers flow at wildly different speeds. But what controls their pace—and how fast can they really go?

The distance that water travels in a river or a stream in general over a given time is known as stream velocity—a dynamic rhythm that defines the river’s pace. Generally speaking, mountain rivers charge ahead with exhilarating speed, while their lowland cousins meander slowly across the plains like lazy serpents in no hurry. And yet, rivers are full of surprises: some even reverse their flow, especially near confluences during times of high water, when swollen currents surge back upstream in defiance of gravity’s usual pull.

A moderately fast river drifts along at around 5 kilometers per hour (or 3 miles per hour), but during floods, streams can roar at speeds of 25 kilometers per hour (or 15 miles per hour)—a wild and unrelenting force.

One of the simplest ways to measure a river’s surface speed is with a GPS device on your boat, just as you would track the velocity of any moving vehicle. Naturally, you shouldn’t paddle—let the river do the work. Alternatively, you can embrace the old-school method: toss a floating object into the current and measure how long it takes to drift across a known distance.

A River’s Many Moods: How Flow Changes with Terrain, Depth, and Season

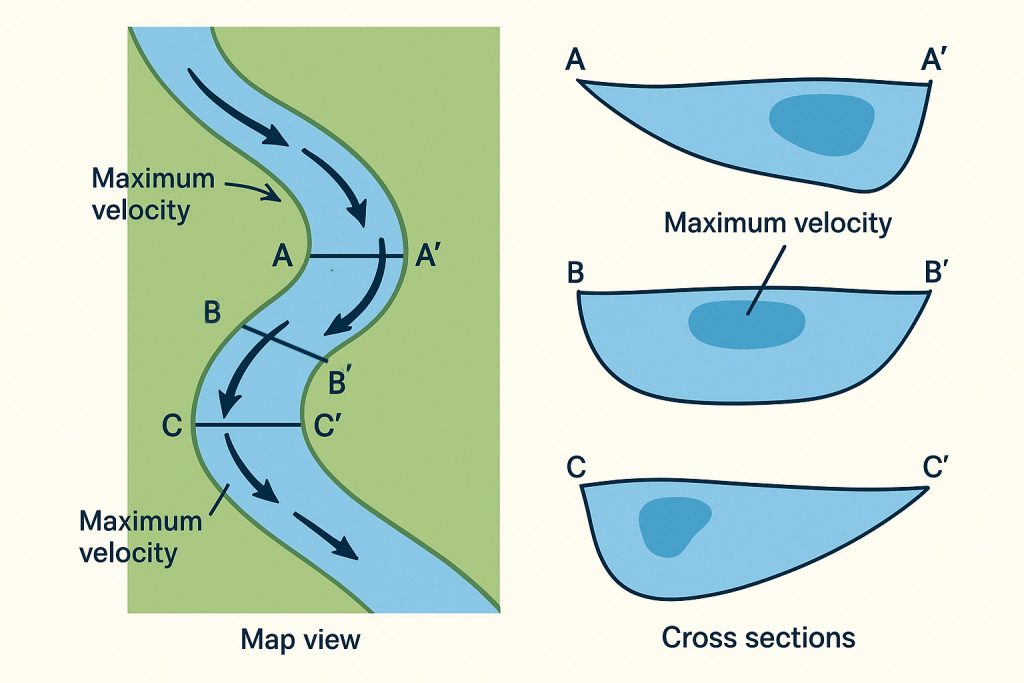

A single river may wear many masks throughout its journey. Its upper reaches, often narrow and steep, tend to race with youthful energy, while the lower stretches slow down, heavy with sediment and maturity. Even one specific section of a river can shift dramatically—from a tranquil glide to a furious tumble through rapids, often in the blink of an eye. Rafters, of course, know this intimately. The current also varies across the same stretch—faster in the center, slower near the banks. And all of it—the tempo, the energy, the direction—dances to the rhythm of the seasons, changing dramatically between low and high water.

Take a cross-sectional look at a stream, and you’ll find its fastest current typically coursing through the middle of the channel—where resistance is lowest and the flow is most uninhibited. But rivers, like dancers, don’t always move in straight lines. When a stream bends around a curve, inertia nudges the swiftest flow toward the outer edge of the bend, carving the bank with relentless precision.

Velocity isn’t just about speed—it’s the river’s lifeblood, the force determining whether it sculpts, carries, or builds. When the current surges with energy, it scours the bed and banks, eroding rock and soil, lifting sediment, and sweeping it downstream. But as the river slows, its grip loosens, and that same sediment settles, forming bars, banks, and deltas. Even slight shifts in velocity can have dramatic consequences—changing not only how much sediment the river holds, but how the landscape itself evolves.

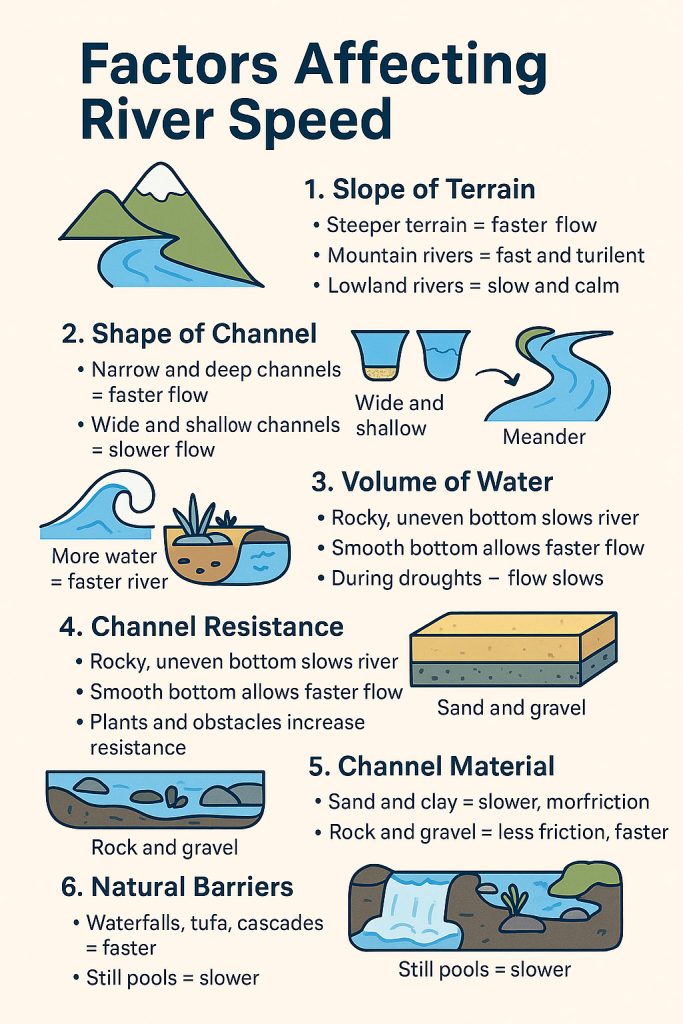

Gradient: The Slope That Shapes a Stream’s Speed

One of the most influential forces behind a stream’s velocity is its gradient—the steepness of its descent. In essence, it’s the tilt of the stream bed or, in massive rivers, the slope of the water surface itself. This downhill angle is typically measured in meters per kilometer (or feet per mile on U.S. maps), providing a simple yet powerful way to understand how rapidly a river loses elevation as it flows.

For example, a gradient of 5 meters per kilometer means the river drops 5 meters vertically for every kilometer it travels horizontally. That might not sound like much—until you step into a mountain stream, where gradients can be wildly steep, plunging 10 to 40 meters per kilometer (or 50 to 200 feet per mile). These streams rush and roar, carving canyons and powering through rocks. In contrast, the mighty lower Mississippi River drifts along almost imperceptibly, with a barely-there gradient of 0.1 meter per kilometer (or 0.5 foot per mile), meandering lazily across the floodplain.

As a rule, a river’s gradient decreases downstream. It begins with a steep, energetic drop in the headwaters and gradually levels out as it approaches the mouth. However, this isn’t a perfect, smooth decline—nature loves its drama. Sudden drops in elevation often create rapids, where the gradient spikes locally, stirring the water into white, frothy chaos before it settles once more into a calmer flow.

Channel Shape and Roughness: The Hidden Sculptors of Stream Speed

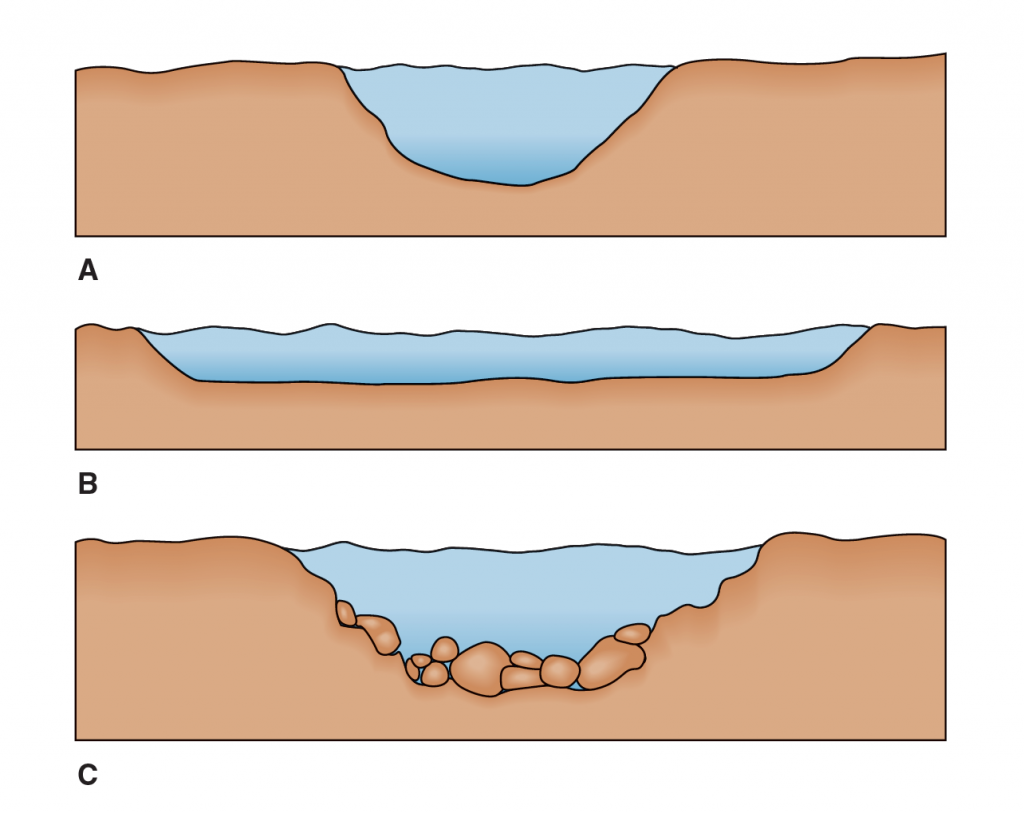

A river’s journey is shaped not only by its slope but also by the form and texture of the path it carves through the land. The shape of the channel plays a crucial role in determining how fast the water flows. As water rushes downstream, it constantly rubs against the bed and banks—this friction acts like an invisible brake, slowing the current. The more contact the water has with its surroundings, the more resistance it meets.

As a stream winds through varying types of rock, its channel adapts. When confined by hard, resistant rock, which erodes slowly, the river is often squeezed into a narrow, tight corridor—like a pressure hose—boosting its speed and power. But when it enters softer, more erodible terrain, the channel may widen dramatically. With that expansion comes more surface area rubbing against the flow, which slows the water down and often leads to sediment deposition—a soft settling as the river loses its grip on what it carries.

Then there’s channel roughness, the texture beneath the surface, which further influences the stream’s pace. A river gliding over a smooth, polished bed can flow swiftly and cleanly. But scatter that same bed with boulders, logs, or coarse gravel, and the story changes—friction mounts, turbulence grows, and the current hesitates.

Even the grain size matters: coarse sediments create far more resistance than fine particles, and a rippled or undulating sand bottom is significantly rougher than one that’s smooth and flat. In the end, it’s these subtle, often unseen features that choreograph the river’s rhythm—speeding it up, slowing it down, and shaping everything in its path.

Volume of Water: Power in the Flow

Another key player in the drama of river speed is the volume of water surging through the channel at any given time—a measure known as discharge. Simply put, the more water a river carries, the faster it tends to move. As the volume swells, so does the river’s energy, pushing it forward with greater force and momentum.

Consider the mighty Amazon or Orinoco, whose colossal flows leave even giants like the Mississippi or Danube trailing in their wake. These vast tropical rivers, swollen with rainfall and countless tributaries, thunder downstream at speeds that mirror their sheer mass.

But volume doesn’t just influence velocity in the moment—it also reshapes the river over time. As discharge increases, the river gains the muscle to erode more aggressively, carving out deeper and wider channels. This expanded pathway, in turn, reduces resistance and allows the water to flow even faster, creating a feedback loop of energy and erosion. In this way, the river’s strength becomes its own architect, gradually transforming the landscape to better serve its ever-growing power.

Certainly! Here’s a descriptive and informative section you can add to a blog post titled “How Fast Are Rivers?” — written in an engaging, National Geographic-inspired tone:

Rivers with Natural Barriers: Waterfalls, Tufa, and Two Faces

Not all rivers flow in a constant rhythm. Some, like Croatia’s stunning Mrežnica River, wear two faces—wild and fast over cascading travertine barriers, then still and serene in the quiet pools between them. These natural barriers, formed by tufa (travertine), create a dynamic mosaic of speed and silence.

Travertine is a type of limestone deposited by mineral-rich waters, often in areas with abundant aquatic plants and mosses. Over centuries, it builds up to form natural dams, steps, and waterfalls that act like speed bumps for the river. Water accelerates dramatically over these obstacles, creating whitewater and froth, only to slow down and spread out into glassy, reflective pools just downstream.

The Mrežnica River, with its 93 travertine barriers, is a perfect example. In some places, it rushes noisily over ledges no taller than a person. In others, it rests in deep, tranquil stretches that resemble a quiet lake. The contrast is so stark, it feels like two rivers woven into one.

These alternating sections of rapid and calm shape biodiversity, filter sediments, and cool the river naturally—all while creating one of the most scenic freshwater landscapes in Europe.

So, how fast are rivers, really?

The answer is: it depends on slopes and seasons, boulders and bends, and rainfall and roughness. From tranquil drifts to thunderous torrents, rivers are in constant negotiation with the landscape, their speed a reflection of everything they touch. Behind every current lies a story of geology, weather, and time—forever flowing, forever changing.