Rivers of South America: Lifelines of a Continent

Discover the mighty rivers of South America—explore their geography, ecology, cultures, and the urgent need for conservation.

From the snow-fed peaks of the Andes to the lush embrace of the Amazon rainforest and the wide, sunburned plains of the Pampas, rivers of South America are more than waterways—they are ancient architects, wild storytellers, and lifelines for millions. These mighty rivers carve the land, shape civilizations, and host one of the richest tapestries of biodiversity on Earth. Welcome to a journey along the rivers that pulse through this dramatic continent.

🏞 Geography & Geology: Sculpted by Time, Shaped by Stone

The rivers of South America are born from dramatic contrasts—a continent forged by fire and chiseled by ice. The towering Andes Mountains, the world’s longest continental mountain chain, stretch like a jagged spine down the western flank of the continent. These snowcapped peaks are not only breathtaking—they are the primary water towers of South America. From here, countless rivers spring to life, fed by glacial meltwaters, highland rainfall, and cloud forest streams.

As these young rivers tumble eastward, they are sculpted by gravity and time, carving their way through high-altitude valleys before fanning out across the vast interior. The result? Some of the world’s most extensive and ecologically vital drainage systems. The Amazon, Orinoco, and Paraná river basins each owe their scale and character to this steep gradient—from mountainous origins to gentle, expansive lowlands.

Beneath this surface drama lies a complex geological foundation. Two ancient landmasses—the Brazilian Shield and the Guiana Shield—form the eastern core of the continent. These billion-year-old cratons resist erosion, channeling rivers around their flanks and creating waterfalls, rapids, and islands. Their mineral-rich soils feed life both in the water and on the land, and they release precious sediments that sustain floodplains downstream.

Meanwhile, the tectonic activity that uplifted the Andes still rumbles today. It has not only given rise to high-altitude lakes like Lake Titicaca, but also creates deep intermontane valleys and active volcanoes that influence river paths, sometimes diverting or damming them entirely.

South America’s river systems, then, are the product of a long and restless history—a delicate interplay of geology, elevation, and climate. They reveal a continent in constant motion, where the past shapes the present in every meander, oxbow, and delta.

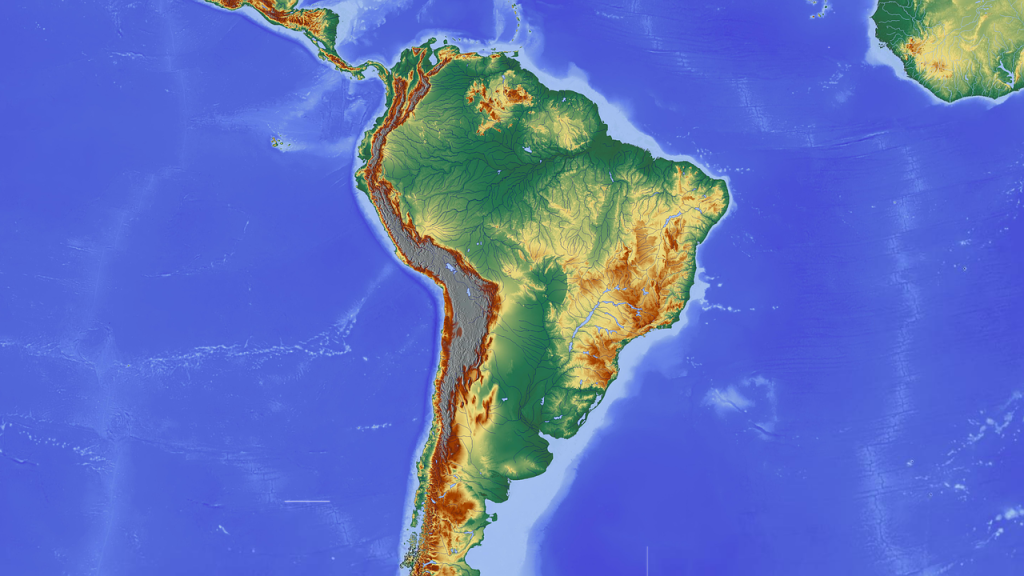

🌊 Major Drainage Basins and Catchments

South America is a continent crisscrossed by colossal drainage basins—immense hydrological realms that channel water, sediment, and life across thousands of kilometers. These river systems are not only impressive in scale; they are also vital engines of biodiversity, agriculture, culture, and economy. Each basin has a distinct personality, shaped by its geography, geology, and climate.

🟢 The Amazon Basin: Earth’s Greatest River Network

By far the largest—and arguably the most iconic—the Amazon Basin sprawls across nine countries and covers over 7 million square kilometers, roughly 40% of the South American landmass. At its heart is the Amazon River, whose staggering volume discharges more water into the ocean than the next seven largest rivers combined. It drains from the glaciers of Peru’s Andes to the Atlantic Ocean, creating an inland sea during rainy seasons. Its tributaries—like the Madeira, Negro, and Tapajós—form a dendritic web of blackwater, whitewater, and clearwater streams, each with its own chemical fingerprint and ecological niche.

🟡 The Orinoco Basin: Savannahs and Swamps of the North

The Orinoco River, rising in the Guiana Highlands of Venezuela and winding over 2,000 km to the Atlantic, defines one of South America’s most ecologically rich yet underexplored basins. Its catchment spans seasonal llanos—vast tropical grasslands flooded in the wet season—creating a vital nursery for fish, birds, and amphibians. A unique feature is the Casiquiare canal, a natural river bifurcation that connects the Orinoco to the Amazon Basin, forming one of the rare links between two major drainage systems.

🔵 The Paraná–Paraguay–Río de la Plata System: South America’s Artery of Trade

Stretching from the Brazilian highlands to the Atlantic coast of Argentina, this river system is the second-largest in South America. The Paraná River, joined by the Paraguay and Uruguay Rivers, flows through agricultural heartlands and urban centers, including Asunción, Rosario, and Buenos Aires. It forms the massive Río de la Plata estuary, a brackish gateway to the Atlantic. Unlike the wild Amazon, this basin is intensely regulated—with locks, dams, and navigation routes serving trade and hydropower.

🟠 The São Francisco River Basin: Brazil’s Cultural Lifeline

The São Francisco River flows entirely within Brazil and is nicknamed the “River of National Integration.” It unites disparate regions, flowing from the tropical savannahs of Minas Gerais through semi-arid hinterlands before turning east to the Atlantic. Historically, it supported early colonization, agriculture, and settlement in the Brazilian interior. Today, it’s a critical source of irrigation and hydropower, though increasingly strained by drought and damming.

🟣 Other Notable Basins

- The Magdalena River Basin in Colombia serves as the country’s principal waterway, vital for transport and fishing.

- The Tocantins–Araguaia system in Brazil, though geographically close to the Amazon, forms a separate basin draining eastward into the Atlantic.

- Numerous Andean Pacific drainages, such as the Santa and Maule Rivers, are short but steep and glacier-fed, sustaining oases in arid western valleys of Peru and Chile.

💧 Hydrology: The Pulse of a Continent

South America’s rivers are a symphony of water in motion—each system flowing to the beat of its own rhythm, shaped by altitude, latitude, rainfall, and geology. The hydrology of these rivers reveals a continent of astonishing contrasts, where torrential deluges, seasonal floods, and vanishing trickles all coexist.

Nowhere is this grandeur more apparent than in the Amazon River, the undisputed hydrological giant of the planet. Fed by relentless rainfall across the equatorial belt and by snowmelt from the Peruvian Andes, the Amazon’s flow volume can exceed 200,000 cubic meters per second during peak discharge—an overwhelming surge that turns the forest into a flooded world. These seasonal pulses inundate an area the size of entire countries, creating a watery wonderland of várzea (flooded forest) and igapó (blackwater forest), where trees adapt to months of submersion and fish swim among trunks.

Further south, rivers like the Paraná and Uruguay demonstrate a different rhythm—strongly seasonal, driven by subtropical rains and shaped by the alternating wet and dry periods of the Pampas. These flood cycles nourish agricultural plains but also bring challenges: droughts that cripple transport and floods that submerge farmland.

In contrast, the rivers of Patagonia, such as the Río Santa Cruz or Río Limay, are born from glacial meltwaters and snowfields. Their flows are often intermittent or modest, but their waters are startlingly clear and icy cold—threads of life winding through arid, wind-scoured steppes. These are rivers that do not flood—they disappear, swallowed by porous basalt or lost in high desert salt pans.

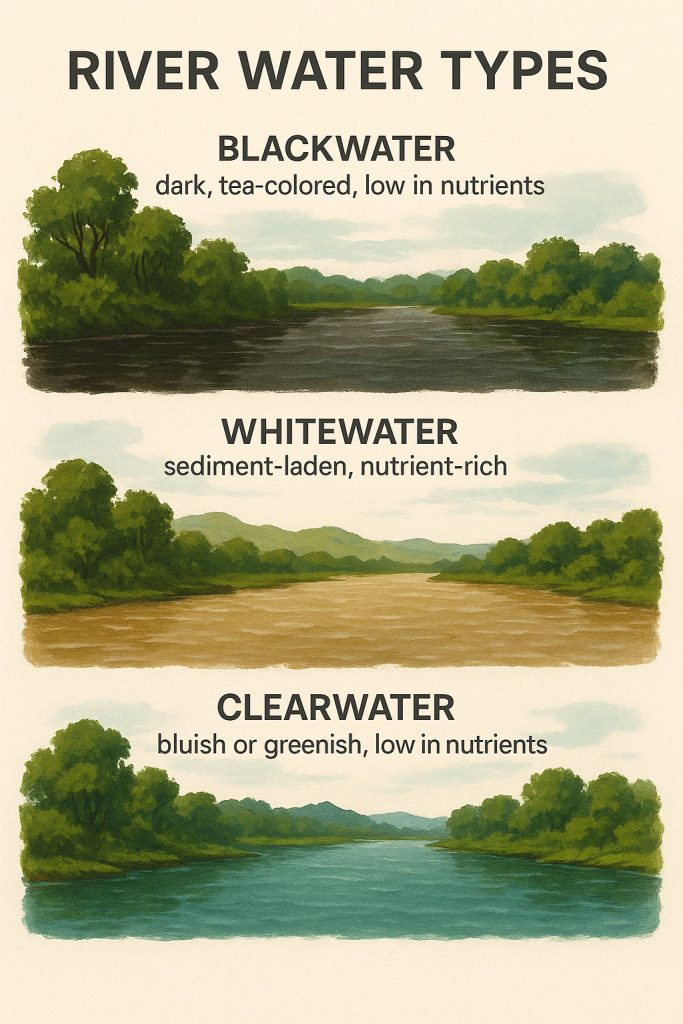

🧪 The Three Water Types: Blackwater, Whitewater & Clearwater

One of South America’s most fascinating hydrological traits is the classification of river water types, particularly in the Amazon Basin, where three distinct water chemistries coexist and intermingle:

- Whitewater Rivers—like the Solimões and Madeira—are nutrient-rich and carry heavy sediment loads from the Andes. Their waters are murky, beige, or light brown, and they fertilize vast floodplains that support agriculture and fish abundance.

- Blackwater Rivers—such as the Rio Negro—are dark, almost tea-colored, stained by tannins from decaying vegetation in sandy, acidic soils. Low in nutrients, they support specialized ecosystems and are often poor in algae, yet rich in unique fish and amphibian species.

- Clearwater Rivers—like the Tapajós and Xingu—have a bluish or green tint with low sediment content and moderate nutrients. Flowing from ancient shields, they typically run over rocky beds and support lush aquatic vegetation.

These three water types—each with its own pH, conductivity, temperature, and mineral content—create hydrological mosaics that allow for extreme biodiversity. Species evolve within these chemical boundaries, and many fish can only survive in a particular water type. The overlapping zones where these rivers meet become crucibles of ecological complexity and evolutionary novelty.

In South America, rivers are more than lines on a map—they are living systems with pulses, chemistry, and character. Their hydrology is as rich and varied as the landscapes they pass through, from cloud forests and mountain passes to savannas, jungles, and deserts. They do not merely move water—they shape life.

🌿 River Ecology: From Frozen Andes to Steamy Tropics

South America’s rivers thread through a breathtaking diversity of ecosystems—from frigid alpine torrents to sultry jungle backwaters. Each ecological zone along these rivers hosts its own cast of characters: aquatic life, birds, mammals, and plants that have adapted in fascinating ways to the rhythms of water, climate, and terrain. These rivers are not just physical features—they are living corridors, shaping evolution and sustaining civilizations.

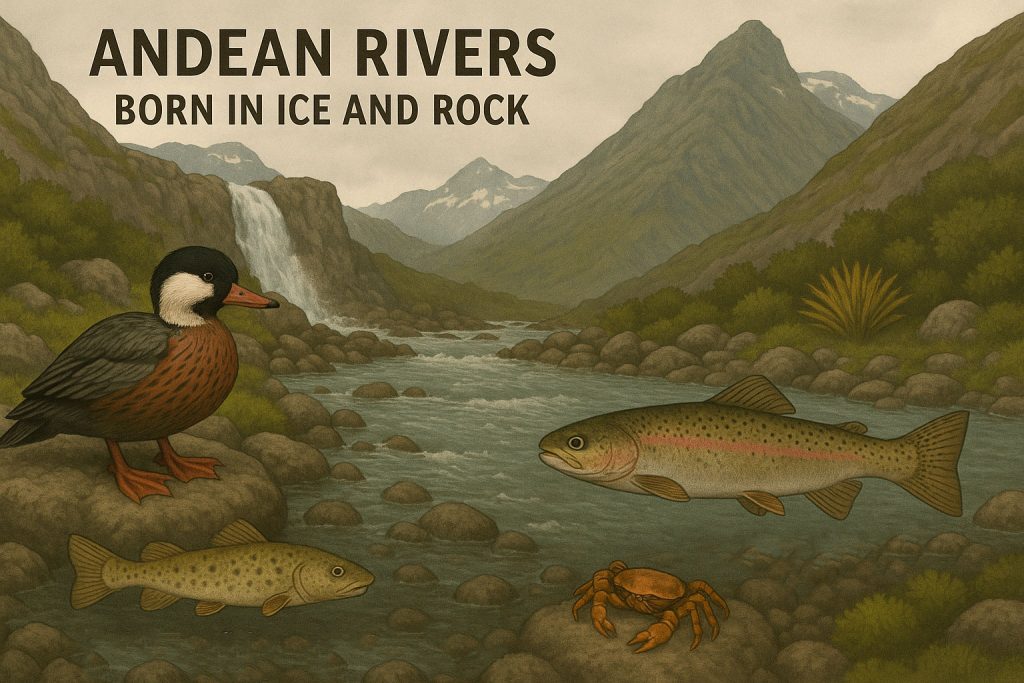

🏔️ Andean Rivers: Born in Ice and Rock

In the high Andes, rivers begin as meltwater streams fed by glaciers and snowfields, slicing through narrow valleys and plunging down rugged terrain. These rivers are oxygen-rich, cold, and fast-flowing, forming niches for specialized species.

Key species & ecology:

- Torrent duck (Merganetta armata) – This remarkable bird surfs through whitewater rapids, nesting on cliffside ledges and diving underwater to forage.

- Andean catfish and freshwater crabs – Cold-tolerant and adapted to low productivity.

- Introduced trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) – While not native, rainbow trout are now widespread in highland streams, often competing with native fish.

- Páramo & puna flora – Vegetation along these rivers includes mosses, bunchgrasses, and cushion plants that thrive in moist, high-altitude conditions.

These rivers also supply water to Andean communities for agriculture and ritual use. Their rapid descent contributes to massive erosion and sediment transport, feeding downstream systems.

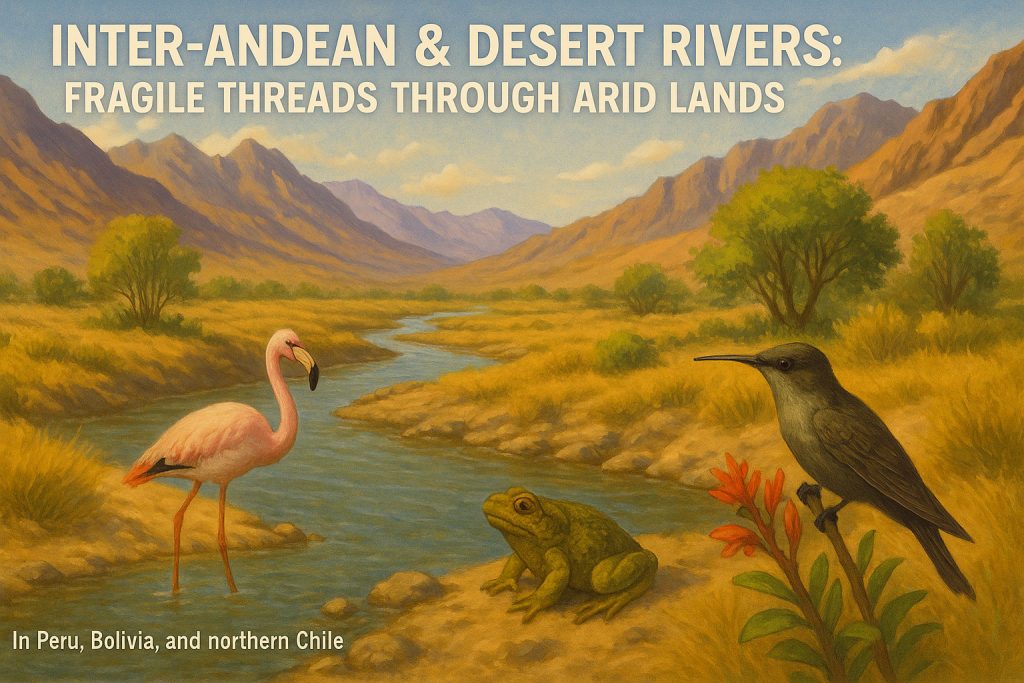

🌵 Inter-Andean & Desert Rivers: Fragile Threads Through Arid Lands

In Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile, some rivers flow through stark deserts and arid intermontane valleys. These are often ephemeral or highly seasonal, sustained by mountain rainfall and glacial runoff. Their ecosystems are delicately balanced.

Key species & ecology:

- Andean flamingo (Phoenicoparrus andinus) – Relies on high-altitude saline lakes and seasonal wetlands.

- Telmatobius frogs – Endangered aquatic frogs found only in Andean streams and thermal springs.

- Giant hummingbird (Patagona gigas) – Feeds along riparian flowering plants.

- Riparian cottonwood and willow groves – Offer shade and stability in otherwise barren terrain.

Despite their modest flow, these rivers are lifelines for pre-Columbian irrigation systems and modern smallholder agriculture. Their delicate hydrology is threatened by glacial retreat and overextraction.

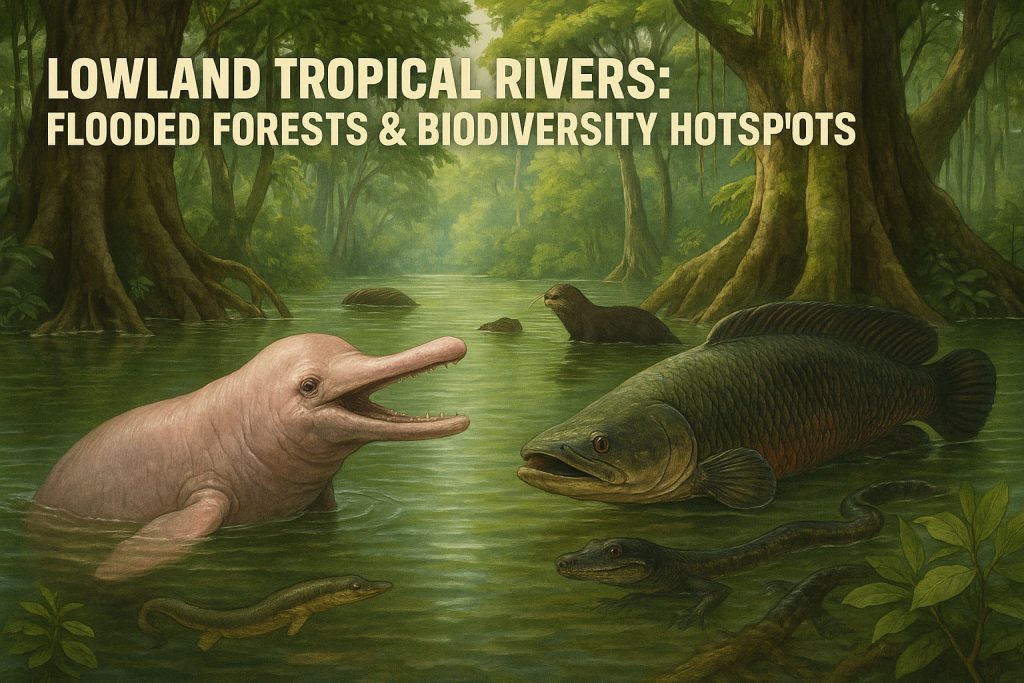

🌴 Lowland Tropical Rivers: Flooded Forests & Biodiversity Hotspots

As rivers descend into the Amazon and Orinoco basins, their ecology transforms into a flood-pulse dynamic—vast areas flood seasonally, giving rise to flooded forests, oxbow lakes, and backwater lagoons teeming with life.

Key species & ecology:

- Pink river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis) – A symbol of the Amazon, this freshwater cetacean navigates submerged forests.

- Arapaima (Arapaima gigas) – One of the world’s largest freshwater fish, air-breathing and adapted to oxygen-poor waters.

- Giant river otter, electric eel, and black caiman – Apex predators and ecological indicators of river health.

- Floodplain trees like Ceiba and Macrolobium – Adapted to months-long submersion.

These rivers function as highways for migration, dispersing fish and seeds, enabling nutrient cycling, and linking distant habitats. Várzea (whitewater floodplains) and igapó (blackwater forests) support contrasting biodiversity due to differences in water chemistry and fertility.

🐟 Pantanal & Paraná Wetlands: Seasonal Surge Zones

The Pantanal, one of the world’s largest wetlands, is a pulsing aquatic plain fed by the Paraguay River. Its river ecology is strongly seasonal, supporting a massive bloom of life during floods.

Key species & ecology:

- Pacu and dorado fish – Important for both ecosystem dynamics and local fisheries.

- Capybara and jabiru stork – Thrive along seasonally flooded banks.

- Marsh deer and anaconda – Symbolic of this rich wetland mosaic.

Farther downstream, the Paraná River meanders into the heavily regulated delta of the Río de la Plata, a transitional zone between freshwater and estuarine systems. It’s a crucial area for migratory birds and riverine commerce, though heavily impacted by dams and pollution.

❄️ Patagonian Rivers: Glacial, Sparse, and Striking

In southern Chile and Argentina, rivers like the Baker, Santa Cruz, and Limay emerge from glaciers and lakes nestled within the Andes of Patagonia. These are cold, swift, and sparsely populated rivers flowing through steppe and temperate forest.

Key species & ecology:

- Magellanic woodpecker & Andean condor – Use riverside cliffs and forests for nesting.

- Native galaxiid fishes – Coldwater specialists now endangered by invasive trout.

- Southern beech forests (Nothofagus) – Hug river valleys, creating stunning autumnal color.

- Río Santa Cruz – One of the last major free-flowing glacial rivers under threat from dam development.

These rivers are geologically young, biologically fragile, and increasingly threatened by hydroelectric megaprojects and tourism pressure.

🏔️ River Features: Sculptors of the South American Landscape

In South America, rivers are more than conduits of water—they are elemental sculptors, endlessly shaping the land with a patient and persistent hand. Over millions of years, they have carved through mountains, molded plains, and laid the very foundation of life. Their legacy is etched in stone, silt, and soil, visible in the dramatic topography and rich ecosystems that ripple across the continent.

🏔 Canyons & Gorges: Etchings in the Andes

Where mountain meets river, drama unfolds. In the Andes, swift rivers plunge through rock to form some of the deepest canyons in the world. The Cañón del Colca in Peru, twice as deep as the Grand Canyon, was hewn by the Río Colca over millennia. These gorges, often inaccessible, are biological refuges and nesting grounds for species like the Andean condor.

Elsewhere, rivers like the Apurímac and Marañón have cut deep, sinuous paths through highland ridges, becoming natural barriers and cradles of cultural identity.

🌋 Valleys & Terraces: Cradles of Civilization

Descending from the Andes, rivers spread into wide, fertile valleys. These fluvial terraces—layered shelves of sediment—are not just geological wonders but fertile lands where Indigenous civilizations like the Inca once thrived. The Sacred Valley of the Incas, carved by the Urubamba River, is a testament to how rivers create landscapes capable of sustaining empires.

🌊 Waterfalls: Power and Majesty in Motion

Few features stir the soul like waterfalls—and South America has some of the most awe-inspiring on Earth.

- Iguaçu Falls: Straddling Brazil and Argentina, this thundering series of 275 cascades is fed by the Paraná River and cloaked in misty rainforest.

- Kaieteur Falls in Guyana plunges from a sandstone plateau in a single drop five times taller than Niagara.

- Countless smaller falls in the Amazon and Andes serve as sacred sites and ecological oases.

🌾 Floodplains: Nature’s Breathing Lungs

In the lowlands, rivers exhale. Every year, rains swell rivers beyond their banks, flooding Pantanal, Los Llanos, and Amazonian forests. These seasonal floodplains are nature’s version of pulse and breath—periodically submerged and then revealed, creating ideal conditions for plant growth, spawning fish, and migrating birds.

- The Pantanal is the world’s largest tropical wetland, shaped by the Paraguay River, a sprawling basin teeming with wildlife.

- Los Llanos of Venezuela and Colombia are vast savannas whose ecology pivots on flood cycles of the Orinoco system.

🌳 Floodplain Forests: Várzea & Igapó

In the Amazon, flooding does not stop at the banks—it engulfs entire forests. Two unique ecosystems emerge:

- Várzea: Whitewater rivers, rich in sediment from the Andes, fertilize forest floors. These areas support towering trees, fruit-bearing plants, and fertile fisheries.

- Igapó: Blackwater rivers like the Rio Negro flow with acidic, nutrient-poor water. Igapó forests are adapted to long submersion and lower productivity, yet house highly specialized life.

Trees in these submerged forests have evolved to withstand months underwater, while fish like the tambaqui feed on fallen fruits and disperse seeds.

🌾 Deltas and Estuaries: Where Rivers Meet the Sea

As rivers reach the ocean, they fan into intricate webs of deltas and estuaries, where salt and fresh water collide and life explodes.

- The Río de la Plata, formed by the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers, is among the broadest estuaries in the world—its brackish waters support marine and freshwater species, migratory birds, and vast fisheries.

- The Orinoco Delta is a labyrinth of channels and forested islands, home to Warao communities who navigate its watery maze in dugout canoes.

From mountain-top torrents to coastal deltas, South America’s rivers are geological storytellers. They wear away mountains and deposit fertile soil, sustain forests that breathe for the planet, and paint the continent in wetlands, waterfalls, valleys, and floodplains. They don’t just shape the land—they define it.

Continent’s most iconic landmarks.

🧑🏽🌾 People Along the Riverbanks

For millennia, South America’s rivers have been more than just physical features—they are spiritual guides, sources of sustenance, and arteries of cultural continuity. The continent’s major river systems have nurtured Indigenous civilizations that see water not as a resource to be used, but as a relative to be respected.

🌿 Indigenous River Cultures: Water as Ancestral Wisdom

In the Amazon Basin, groups such as the Yanomami, Tikuna, Kichwa, and Kayapó maintain complex relationships with riverine landscapes. Rivers are central to their cosmologies—often personified as gods or spirit ancestors—and determine the rhythm of daily life: fishing, farming, ritual bathing, and gathering medicinal plants.

- The Yanomami build communal houses (shabonos) along tributaries, moving seasonally with fish migrations and fruiting cycles.

- The Tikuna, along the Solimões River, practice floodplain agriculture and intricate fishing techniques adapted to the varzea flood-pulse system.

- Along the Orinoco, the Warao people live in palafitos—stilted homes above water—and navigate a watery maze in dugout canoes, their language and lifeways inseparable from the delta they inhabit.

In the south, the Guaraní people settled along the Paraná River and its tributaries, relying on shifting cultivation and aquatic biodiversity, with their myths tracing origin stories to springs and waterfalls.

Rivers, for these cultures, are timekeepers. They mark the planting and harvesting seasons, determine feast and fasting days, and guide travel and trade routes. Even songs and oral histories follow the curves of the rivers they describe.

🌆 Modern River Cities: The Urban Pulse of Water

As colonization and industrialization spread, riverbanks became hubs of economic activity and urban growth. Major cities grew not in spite of rivers—but because of them:

- Manaus, once a rubber boomtown, sits at the confluence of the Negro and Solimões Rivers, surrounded by rainforest but accessible by cargo ships.

- Belém, a colonial port city near the Amazon’s mouth, became a gateway for goods, people, and ideas moving between the forest and the Atlantic.

- Buenos Aires, one of South America’s largest cities, lies on the Río de la Plata, drawing its power, prosperity, and pollution challenges from this vast estuary.

- Asunción, Paraguay’s capital, developed along the Paraguay River, a lifeline for the otherwise landlocked country’s trade and agriculture.

Even smaller towns like Iquitos in Peru and Santarém in Brazil remain reachable only by air or river, with boats—not cars—serving as taxis, trucks, and lifelines. In the Pantanal, floating schools and clinics serve rural populations cut off during the wet season.

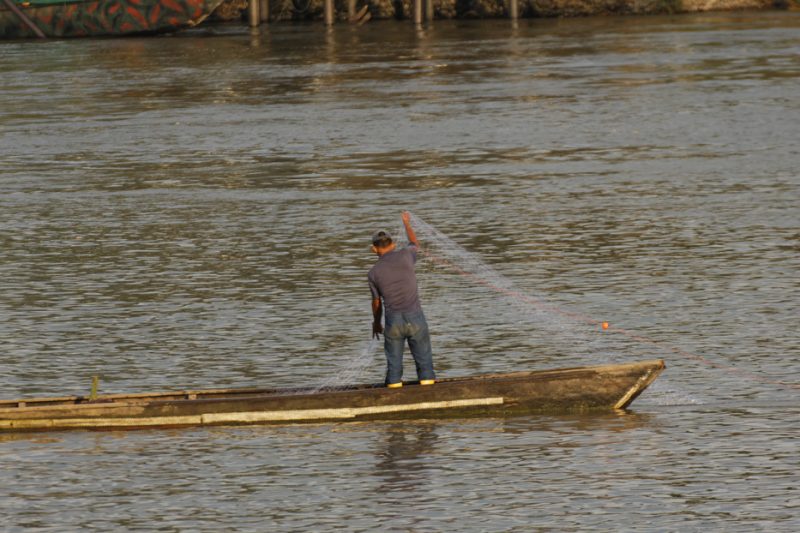

🚤 Rivers as Modern Arteries: Commerce, Culture, and Conflict

Today, rivers are still essential to hydroelectric power (e.g., Itaipú and Belo Monte dams), irrigation for soy and cattle farming, and industrial navigation. But this use has come with conflict: dams flood Indigenous territories, fisheries collapse under pollution, and ancestral lands are lost to monoculture and mining.

Yet amidst all this, rivers also remain cultural stages. Festivals like the Cirio de Nazaré in Belém and Semana Santa river processions turn rivers into ceremonial routes. In Colombia, musicians paddle down the Magdalena River during cumbia festivals, keeping alive traditions tied to the tides and currents.

Across jungle villages, Andean valleys, bustling ports, and modern capitals, rivers still shape South American identity. They are lifelines and lifeways, sacred spaces and economic corridors, reminders that the continent’s greatest stories often begin—not on land—but in the gentle bend of a river.

⚠️ Threats and Conservation Challenges

DeBeneath their grandeur and seeming inexhaustibility, South America’s rivers face mounting threats—pressures that erode not only ecosystems but also the cultures and economies that depend on them. What was once a continent of wild, untamed waterways is increasingly fragmented, contaminated, and overexploited. The challenges are vast, interconnected, and accelerating.

🌲 Deforestation & Agricultural Expansion: Erosion and Contamination

Nowhere is the clash between nature and industry more visible than in the Amazon Basin, where rampant deforestation clears land for cattle ranching, soy plantations, and illegal logging. Without trees to anchor the soil and cycle rainfall, rivers suffer:

- Sedimentation chokes waterways, smothers fish-spawning grounds, and disrupts aquatic food chains.

- Agricultural runoff laced with pesticides, fertilizers, and animal waste creates toxic blooms and dead zones, particularly in the floodplains and tributaries.

- Once-pristine blackwater and clearwater streams become murky corridors of erosion, carrying the scars of upstream exploitation.

⚡ Dams & Hydropower: Energy vs. Ecology

Hydroelectric dams promise clean energy—but at immense ecological cost. The Itaipú Dam on the Paraná and the Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River have flooded entire valleys, displaced Indigenous communities, and cut off migratory routes for fish like the dorados and piracemas that once moved freely along the current.

- Reservoirs trap sediment, starving downstream wetlands and deltas of nutrients.

- Altered flow regimes confuse spawning cycles, especially in flood-dependent systems like the Pantanal and Amazon.

- Some rivers—once living, breathing entities—are now reduced to artificial trickles between concrete barriers.

⛏️ Mining & Mercury Pollution: Gold at a Terrible Price

In the Andean highlands and Amazon lowlands, illegal gold mining has surged. The quest for precious metals brings with it a silent toxin: mercury.

- Mercury used to bind gold leaches into rivers, accumulating in fish and entering human diets—especially devastating for Indigenous communities who rely on river protein.

- Rivers like the Madre de Dios in Peru now carry not just silt, but poison.

- Legal mining also contributes to heavy metal runoff, acid mine drainage, and widespread habitat destruction.

🌧 Climate Change: Shifting the Rhythm of the Rivers

Global warming alters the very heartbeat of South America’s rivers.

- Glacial melt in the Andes increases flows in the short term, but as glaciers retreat, dry seasons become longer and rivers falter.

- Erratic rainfall driven by climate anomalies like El Niño intensifies both droughts and floods—devastating crops, collapsing riverbanks, and overwhelming urban drainage systems.

- Rising sea levels intrude into river deltas like the Amazon and Orinoco, salting freshwater systems and displacing human and animal communities.

🌍 Conservation & Resistance: Guardians of the Waters

Despite grim headlines, rivers are not without defenders. Across the continent, efforts to protect, restore, and respect river systems are gaining momentum:

- Indigenous-led conservation: Groups like the Kayapó and Asháninka manage vast territories using traditional ecological knowledge, often more effectively than state-led programs.

- Biosphere reserves and Ramsar sites: Protect critical wetland habitats, like the Llanos de Moxos and the Amazon Headwaters.

- Community-based monitoring: Locals track river health using both scientific tools and ancestral indicators.

- Transboundary water governance: Frameworks like the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) and La Plata Basin Agreement aim to coordinate management across political borders—though enforcement remains inconsistent.

Still, these efforts are too often underfunded, overlooked, or undermined by extractive interests and weak regulation. The challenge is not simply ecological—it is political, cultural, and economic.

🌅 Conclusion

To understand South America, you must follow its rivers. They are threads that weave the continent’s past, present, and future. Wild and winding, nourishing and threatened, South America’s rivers are among the most vital and vibrant on Earth. To protect them is to protect the heart of the continent itself.