Not Just Water: When Sediment Flows Too

It’s not just water that flows—sediment, sand, and gravel move too, shaping the river’s course and deeply influencing its dynamics.

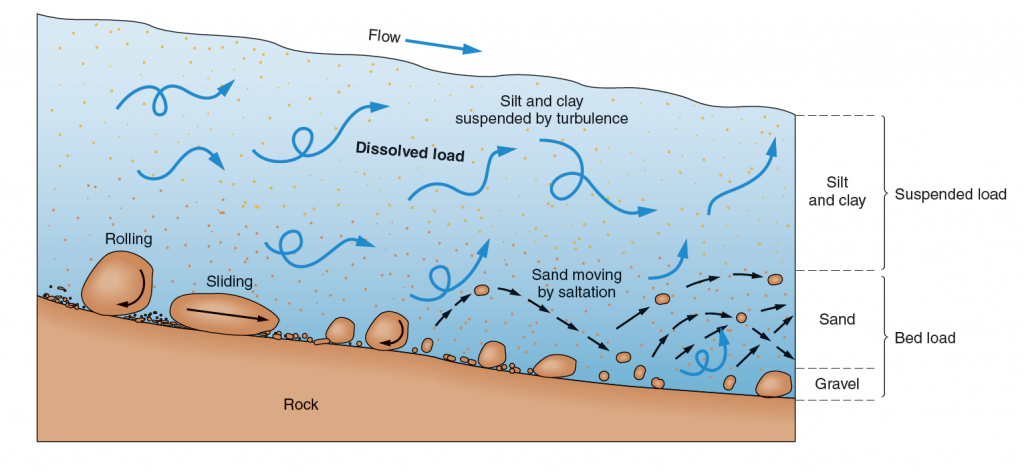

The energy of the stream is spent on river erosion, where the water current breaks the bedrock and sends the rocks downstream. The sediment load transported by a stream can be subdivided into bed load, suspended load, and dissolved load. Most of a stream’s load is carried in suspension in solution.

The bed load

The bed load is the large or heavy sediment particles that travel on the streambed. Sand and gravel, which form the usual bed load of streams, move by either traction or saltation. Large, heavy particles of sediment, such as cobbles and boulders, may never lose contact with the streambed as they move along in the flowing water. They roll or slide along the stream bottom, eroding the streambed and each other by abrasion. Movement by rolling, sliding, or dragging is called traction. As a result, the rocks become rounded and polished. If you dip your head inside the water, you can even hear the pebbles hitting each other.

Sand grains or smaller pebbles move by traction, but they also move downstream by saltation, a series of short leaps or bounces off the bottom. Saltation begins when sand grains are momentarily lifted off the bottom by turbulent water (eddying, swirling flow).

The force of the turbulence temporarily counteracts the downward force of gravity, suspending the grains in water above the streambed. The water soon slows down because the velocity of water in an eddy is not constant; then, gravity overcomes the lift of the water, and the sand grain once again falls to the bed of the stream.

While it is suspended, the grain moves downstream with the flowing water. After it lands on the bottom, it may be picked up again if turbulence increases, or it may be thrown up into the water by the impact of another falling sand grain. In this way, sand grains saltate downstream in leaps and jumps, partly in contact with the bottom and partly suspended in the water.

The suspended load

The suspended load is sediment that is light enough to remain lifted indefinitely above the bottom by water turbulence. The muddy appearance of a stream during a flood or after a heavy rain is due to a large suspended load. Silt and clay usually are suspended throughout the water, while the coarser bed load moves on the stream bottom.

The suspended load has less effect on erosion than the less visible bed load, which causes most of the abrasion of the streambed. Vast quantities of sediment, however, are transported in suspension. You can experience the transport of the suspended load while paddling during the high water, the constant hissing of the sand against the boat.

The dissolved load

Soluble products of chemical weathering processes can make up a substantial dissolved load in a stream. Most streams contain numerous ions in solution, such as bicarbonate, calcium, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. The ions may precipitate out of the water as evaporite minerals if the stream dries up, or they may eventually reach the ocean.

Very clear water may, in fact, be carrying a massive load of material in solution, for the dissolved load is invisible. Only if the water evaporates does the material become visible as crystals begin to form. One estimate is that rivers in the United States carry about 250 million tons of solid load and 300 million tons of dissolved load each year. It would take a freight train eight times as long as the distance from Boston to Los Angeles to carry 250 million tons.

The effect of the velocity on the sediment transport

The dissolved load is the fastest (virtually the speed of the river), while the bed load is the slowest. River velocity is a key variable in sediment transport, an indicator of the energy of the stream. For each grain size, these velocities are different. Sand and silt are light, so they can be transported even by slow rivers. Gravel and boulders are heavier, and this requires much faster current to start moving them.

It takes a higher stream velocity to erode grains (set them in motion) than to transport grains (keep them in motion). No sediment moves until the velocity is high enough. As the flood recedes, the velocity drops below the upper curve and into the transportation area. Under these conditions, the sand that was already eroded continues to be transported, but no new sand is eroded.

As the velocity falls below the lower curve, all the sand is deposited again, coming to rest on the streambed. The coarser particles require progressively higher velocities for erosion and transportation, as boulders are harder to move than sand grains).

Fine-grained silt and clay are actually harder to erode than sand. The reason is that molecular forces tend to bind silt and clay into a smooth, cohesive mass that resists erosion. Once silt and clay are eroded, however, they are easily transported. The silt and clay in a river’s suspended load are not deposited until the river virtually stops flowing.

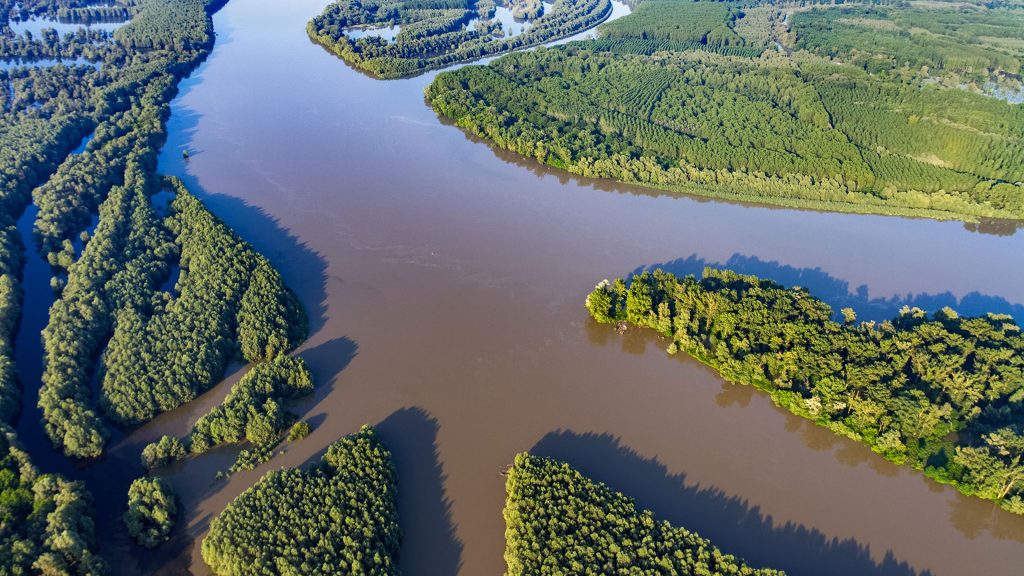

The importance of the sediment transport

In the mountains, a river is a sculptor—carving its bed and sending fragments tumbling down. As it winds through gentler middle reaches, its force softens; heavier loads keep moving, but lighter particles begin to settle. It dances side to side, nibbling at its banks and sketching wide meanders.

By the time it reaches the plains, the river slows to a whisper, laying down its silken cargo of sand and silt. This ever-shifting rhythm of erosion and deposition is the heartbeat of river life—vital to nurturing rich, thriving biodiversity.