Rivers of Canada: From Arctic Wilds to Temperate Forests

Discover the rivers of Canada—from Arctic giants to salmon streams. Explore their geography, ecology, hydrology, and conservation challenges.

The rivers of Canada are among the longest, wildest, and most ecologically vital waterways on Earth. Stretching from icy Arctic deltas to temperate rainforests and prairie plains, they shape the land, support rich biodiversity, and sustain countless communities. In this guide, explore the geography, hydrology, and unique features of Canada’s river systems—plus the challenges they face in a changing world.

🌎 Geography & Geology: Carved by Ice, Fed by Mountains

The rivers of Canada are ancient storytellers, their courses etched into the land by the immense forces of ice, rock, and time. During the last Ice Age, vast glaciers blanketed most of the country, grinding across the surface with unimaginable weight. As they advanced, they scoured the bedrock, carving deep U-shaped valleys and leaving behind vast depressions. When the ice retreated around 10,000 years ago, meltwater surged through these freshly carved corridors, giving birth to many of the river systems we see today.

Canada’s diverse geography creates dramatic contrasts in river morphology. In the Rocky Mountains, steep gradients generate swift, clear torrents, tumbling down rugged valleys and sculpting waterfalls, canyons, and alluvial fans. By contrast, the Canadian Shield—an ancient, weathered expanse of Precambrian rock—hosts rivers that are slower, older, and often meandering, winding through granite outcrops and boreal forest.

Further east, the Appalachians offer shorter, steeper rivers, while in the Prairies, rivers cut deeply into loess and sedimentary plains, forming vast floodplains and oxbow lakes. Meanwhile, in the Arctic tundra, rivers like the Coppermine and Thelon snake slowly through permafrost-dominated terrain, often frozen for much of the year.

In essence, Canada’s rivers are the visible veins of a powerful geological past—fluid maps of an ever-changing land, shaped by fire, crushed by ice, and carried forward by flowing water.

🧊 Glacial Legacy and the “Youth” of Canadian Rivers

Many of Canada’s rivers are geologically young, especially compared to rivers in unglaciated regions like Africa or parts of Asia. This youthful status is due to the massive reshaping of the landscape by glaciers during the last Ice Age (the Pleistocene epoch, which ended roughly 11,700 years ago).

Here’s why:

- Glaciers erased older drainage systems. As the ice sheets advanced, they scoured away ancient river valleys and completely restructured the topography beneath them. When the glaciers melted, new rivers formed in the freshly exposed terrain—often following paths of least resistance carved by the retreating ice or dammed meltwater.

- Many rivers are still finding equilibrium. Because of this, many Canadian rivers are still actively carving their valleys, adjusting their courses, and depositing sediments. In geological terms, this behavior is characteristic of youthful rivers—marked by steeper gradients, rapids, waterfalls, and less meandering.

- Postglacial rebound affects flow. The land is still rebounding (isostatic rebound) from the weight of the glaciers. This ongoing uplift continues to alter river gradients and drainage directions—another hallmark of a young and dynamic fluvial system.

- Lakes and wetlands dominate glaciated regions. Glaciers also left behind thousands of lakes and depressions. Many rivers begin or pass through these glacially carved lakes, giving Canadian waterscapes a distinctive patchwork of interconnected water bodies.

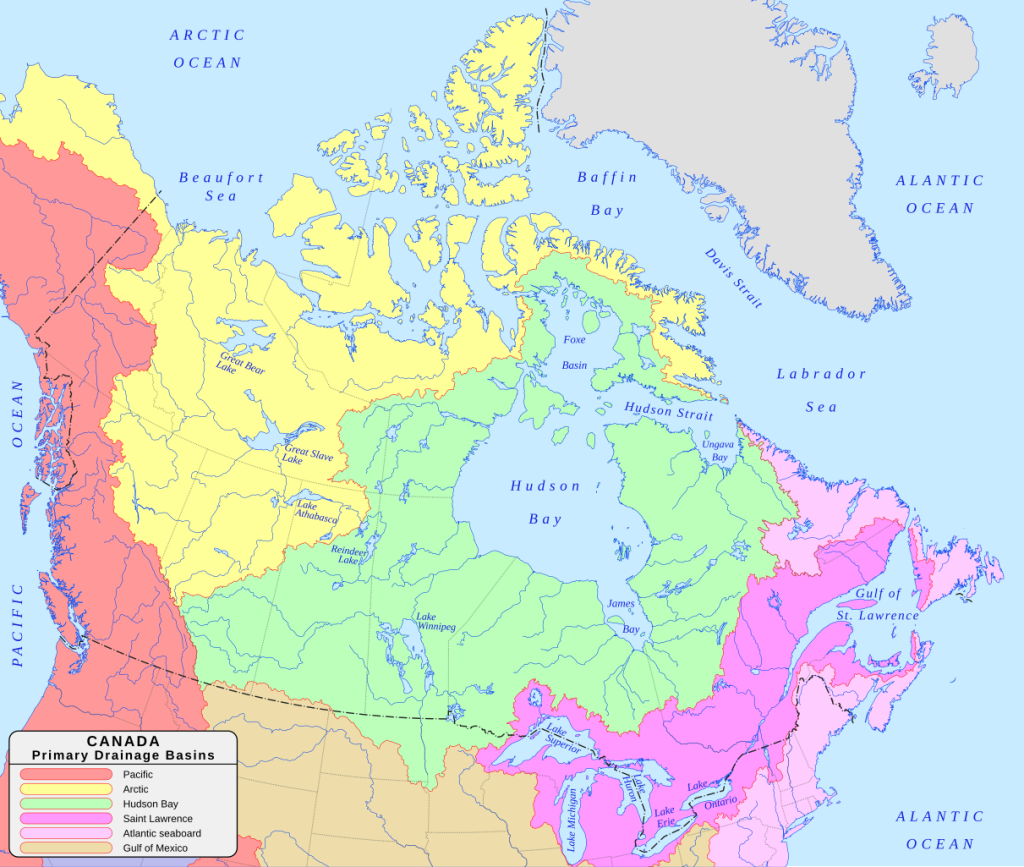

🌊 Major Drainage Basins and Catchments

Canada’s vast and varied landscape is drained by five major basins—each one a colossal system of rivers, lakes, wetlands, and tributaries that channel freshwater across the continent. These drainage basins are not just hydrographic zones; they are dynamic regions shaped by geology, ecology, and culture.

🧊 1. Arctic Ocean Basin

Covering over 3.5 million square kilometers, this is Canada’s largest drainage basin by area. Dominated by the mighty Mackenzie River, the second-longest river system in North America, it carries waters from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and the Northwest Territories into the Beaufort Sea. The Mackenzie’s watershed includes remote boreal forests, sprawling muskeg, and permafrost plains—home to moose, caribou, and migratory birds. Its northern flow makes it an essential corridor for climate studies, Indigenous cultures, and ecological monitoring in a warming Arctic.

2. Hudson Bay Basin

This vast inland basin gathers runoff from much of central Canada, stretching from the Prairies to northern Ontario and Quebec. Major rivers like the Churchill, Nelson, and Saskatchewan funnel their waters into the massive inland sea of Hudson Bay. Once part of the ancient glacial Lake Agassiz, the basin is a land of cold winters and long, slow-moving rivers. It’s rich in wetland ecosystems, particularly important for waterfowl and wading birds, and historically served as a trade route during the fur trade era via the Hudson’s Bay Company.

3. Atlantic Ocean Basin

Flowing eastward, this basin includes some of the country’s most iconic rivers, including the Saint Lawrence River, which connects the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. The Saint Lawrence is both a natural wonder and a heavily engineered shipping corridor, serving as Canada’s economic lifeline. Other rivers like the Miramichi and Sainte-Anne drain the Maritimes, flowing through lush Acadian forests and into the cold Atlantic. This basin supports vibrant ecosystems, world-class salmon runs, and historic settlements dating back to the earliest days of European colonization.

4. Pacific Ocean Basin

Fed by snowmelt and glacial runoff from the Canadian Rockies, rivers in this basin rush westward through narrow valleys and coastal rainforests. The Fraser River, British Columbia’s longest, is legendary for its sockeye salmon runs and plays a crucial role in the province’s economy, ecology, and Indigenous cultures. The Skeena and Columbia (via the Kootenay) also contribute to this basin. With steep gradients, rapids, and deep canyons, these rivers are energetic, erosive forces carving one of the most dramatic landscapes in North America.

5. Gulf of Mexico Basin

Though only a sliver of Canada contributes to this basin, it is a geographical curiosity. The Milk River, rising in Alberta, flows south into the Missouri River, eventually joining the Mississippi River and emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. It’s the only part of Canada whose waters flow into the Caribbean Sea system. The Milk River Valley, semi-arid and starkly beautiful, is rich in dinosaur fossils and Indigenous history.

Each basin is a distinct ecological world, defined by its climate, topography, wildlife, and human history. They act like natural borders—dividing the flow of water, but uniting landscapes under a shared rhythm of rainfall, snowmelt, and seasonal flood. Understanding these basins is key to protecting Canada’s freshwater legacy in the face of growing environmental pressures.

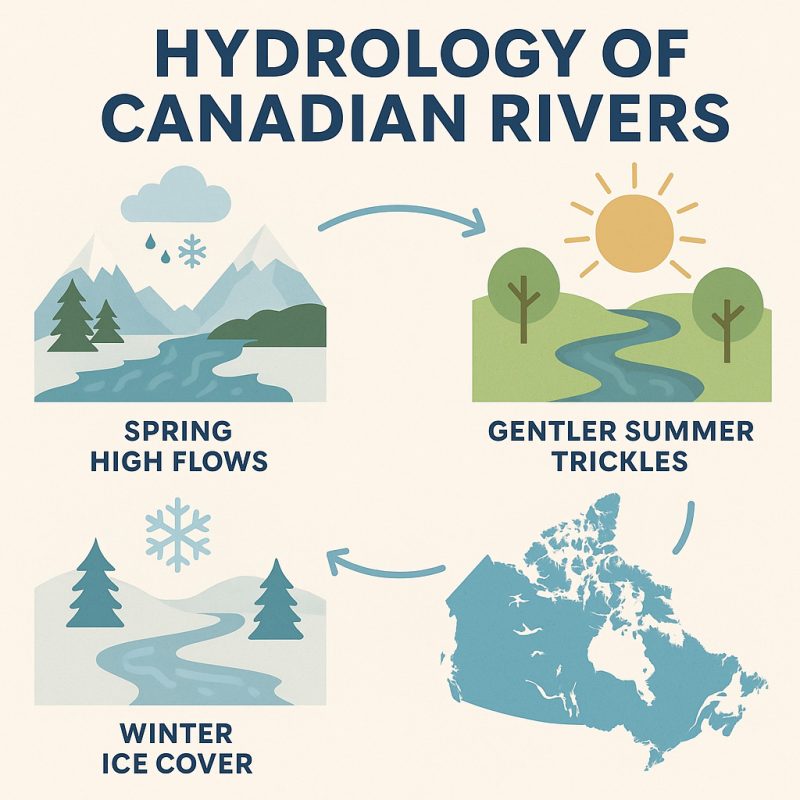

💧 Hydrology: Power in Motion

Canada’s rivers are in constant flux—ever-shifting bodies of water sculpted by season, temperature, and terrain. Their hydrology is a symphony of snowmelt, glacial pulse, rainfall, and freeze, orchestrated across one of the most climatically diverse countries on Earth.

In spring, rivers across the country roar to life. As mountain snowpacks melt and glaciers shed their icy skins, water rushes into valleys and floodplains, turning modest streams into thundering torrents. These freshet events replenish wetlands, carve new channels, and feed spawning grounds—but they also pose risks, occasionally breaching banks and washing out roads, especially in the Prairies and mountainous regions.

In summer, river flows ease. Many rivers shrink to gentle currents or expose dry gravel bars, especially in interior plateaus or arid zones like southern Alberta. But in coastal British Columbia, fed by the Pacific’s wet embrace, rivers like the Skeena and Fraser remain full-bodied year-round, bolstered by rain and glacial melt. These rivers, heavy with sediment, build vast deltas and nourish some of the most productive salmon habitats on the planet.

Winter writes a different story. In the North and across much of central Canada, rivers freeze solid for several months. Ice becomes a seasonal highway, enabling travel, hunting, and supply transport in remote communities, particularly in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Under the ice, flow continues—slow, muffled, but alive.

Among the giants, the Mackenzie River stands supreme. Stretching 4,241 kilometers from the Great Slave Lake to the Arctic Ocean, it drains nearly one-fifth of Canada’s landmass. It is slow, deep, and majestic—a northern Amazon. Meanwhile, rivers like the Fraser, though shorter, are more energetic and sediment-rich, carving steep valleys and depositing nutrient-rich silt into the Fraser Delta, one of Canada’s most ecologically and economically vital regions.

Hydrologically, Canada’s rivers are responsive and powerful, reflecting the rhythms of the natural world. They link glaciers to oceans, mountains to plains, and forests to the sea—translating geography into motion, and weather into flow.

🌿 River Ecology: From Arctic to Temperate

Canada’s rivers are not merely streams of flowing water—they are living, breathing ecosystems that stretch across five major ecozones, each with distinct climates, species, and hydrological rhythms. As they wind from glacier to sea, from tundra to tidepool, Canadian rivers support astonishing biodiversity and form the backbone of vast, interconnected food webs.

❄️ Arctic Rivers: Lifelines of the Frozen North

In the far north, rivers like the Coppermine, Thelon, and Back meander through tundra and permafrost. Here, life is short-seasoned but intense. These rivers carry icy meltwater across barren lands dotted with lichens, sedges, and dwarf willows, home to muskoxen, Arctic foxes, and snowy owls. The Arctic char, a cold-adapted relative of the trout, migrates between freshwater and the sea, spawning in gravelly riverbeds. These rivers are often frozen more than half the year, yet they remain vital to Indigenous communities, who rely on them for travel, fishing, and cultural traditions.

🌲 Boreal Rivers: The Veins of the Northern Forest

Covering more than half of Canada’s landmass, the boreal forest is threaded with rivers that are darker, slower, and lined with spruce, birch, and larch. Rivers like the Churchill, Nelson, and Athabasca pass through muskeg bogs, wetlands, and dense forest, creating critical nesting grounds for waterfowl like loons, mergansers, and Canada geese. Moose wade among willows, wolves shadow the banks, and massive beaver dams reshape water flow. These rivers are particularly sensitive to industrial impacts like logging, hydro dams, and mining, yet they remain among the least disturbed ecosystems on Earth.

🍁 Temperate Rivers: Cradles of Salmon and Biodiversity

In the west and southeast, temperate rivers like the Fraser, Skeena, and St. Lawrence pulse with energy and complexity. The Fraser River, for instance, is one of the world’s great salmon rivers—its seasonal runs bring millions of sockeye, coho, and chinook from ocean to spawning grounds, feeding bears, eagles, orcas, and even forest soil in a nutrient cycle that links mountain and sea. Temperate rivers also support riparian woodlands, amphibians like salamanders and frogs, and insects essential for fish and bird diets. These ecosystems are also among the most human-influenced, yet they remain ecological powerhouses when managed well.

🌾 Prairie Rivers: Resilient Threads of the Grasslands

Canada’s prairie rivers—such as the Assiniboine, Red, and South Saskatchewan—are often overlooked but ecologically rich. They flow through semi-arid grasslands and glacial till plains, often meandering, shallow, and sediment-heavy. Their floodplains and oxbow lakes provide breeding grounds for amphibians and shorebirds, while species like white-tailed deer, burrowing owls, and coyotes depend on their water. These rivers are dynamic—prone to flooding and drought—and require delicate water management in a landscape increasingly affected by agriculture and climate change.

🌊 More Than Waterways: Rivers as Ecological Highways

From north to south, east to west, Canada’s rivers connect ecosystems across vast distances. They carry nutrients, sediments, and species, and serve as migration corridors for fish, birds, and even mammals. Beaver dams, salmon carcasses, and floodplain forests are all part of a resilient, evolving system that depends on free-flowing, healthy rivers.

These rivers are not just water—they are the beating heart of Canadian nature. And protecting them means protecting everything that lives along their banks, swims through their currents, and drinks from their flow.

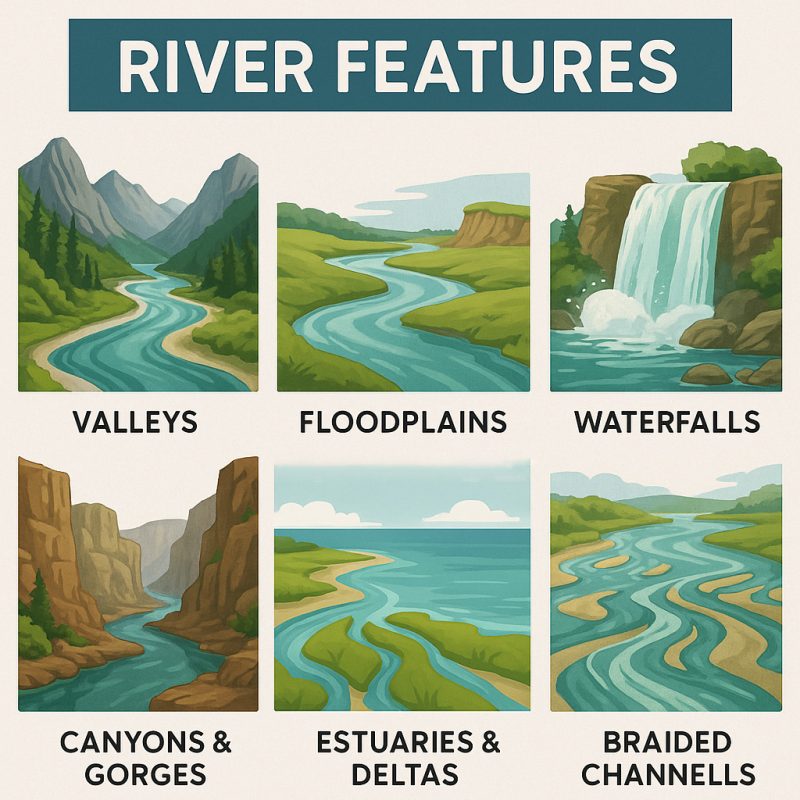

🏞 River Features: Sculptors of the Canadian Landscape

Canada’s rivers are not passive waterways—they are active architects, carving, reshaping, and defining the very surface of the continent. Over thousands of years, flowing water has sculpted an astonishing variety of landforms, from deep canyons to sweeping floodplains, meandering valleys, and fertile estuaries. Each feature tells a story of force, erosion, and renewal.

🏔 Valleys: Water’s Longest Signature

River valleys stretch like signatures across Canada’s terrain. In the Rocky Mountains, rivers like the Kicking Horse and Bow trace sharp V-shaped valleys through rugged peaks—formed by steep gradients and powerful currents. Further east, glacial activity widened many of these into U-shaped valleys, later reoccupied by rivers. In gentler regions, such as the St. Lawrence Valley, rivers carved broad, fertile troughs that became corridors of human settlement, trade, and agriculture.

🌊 Floodplains: Dynamic Cradles of Life

Where rivers slow down—like in the Prairies or southern Ontario—they spread out, depositing silt and creating wide floodplains. These areas, such as the Red River Valley, are incredibly fertile but also prone to seasonal flooding. Floodplains are ecological powerhouses: they nourish wetlands, recharge groundwater, and provide crucial breeding grounds for amphibians, birds, and fish. Many Indigenous settlements and modern cities have grown on these lands, drawn to the richness they offer.

🕳 Canyons and Gorges: Water vs. Stone

In places where rivers meet hard bedrock and steep elevation drops, they cut spectacular canyons and gorges. The Nahanni River, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, slices through the Mackenzie Mountains, forming towering limestone cliffs, thermal springs, and plunging waterfalls. In Quebec, the Jacques-Cartier River flows through a dramatic glacial valley more than 500 million years in the making. These deep cuts in the Earth reveal ancient rock layers and tell stories of a time before humanity.

🌿 Deltas and Estuaries: Where Rivers Meet the Sea

At the mouth of Canada’s great rivers, freshwater meets saltwater in estuaries and deltas—rich zones of biological productivity. The Fraser River Delta, for example, is one of North America’s most important migratory bird habitats, while the St. Lawrence Estuary teems with marine life, including beluga whales and seals. These areas act as buffers against storm surges and provide essential nurseries for fish and shellfish, linking river ecosystems to ocean food webs.

🌀 Braided Channels, Meanders & Oxbows: Rivers in Motion

Across the Yukon and the Mackenzie River Basin, many rivers split into braided channels, creating shifting networks of islands, bars, and sandbanks. In slower-flowing rivers, like those in the southern Prairies, rivers often meander—snaking across the land and sometimes cutting off sections to form oxbow lakes. These features highlight the restless energy of water and the perpetual reshaping of land through erosion and deposition.

💦 Waterfalls

Few features are as dramatic—or iconic—as waterfalls. Canada’s rivers drop over cliffs, plunge through canyons, and thunder into deep pools, creating Niagara Falls, Helmcken Falls, Athabasca Falls, and many more. Waterfalls are powerful erosive agents, forming plunge pools and mist-filled microclimates that support mosses, ferns, and cliffside nesting birds. They also hold deep cultural meaning and attract millions of visitors every year.

From tranquil oxbow lakes to roaring falls, Canada’s river features are living monuments to water’s power and patience. They shape not only the landscape but also the lives and stories of those who live along their banks. Understanding these features means understanding the rhythm of Canada itself.

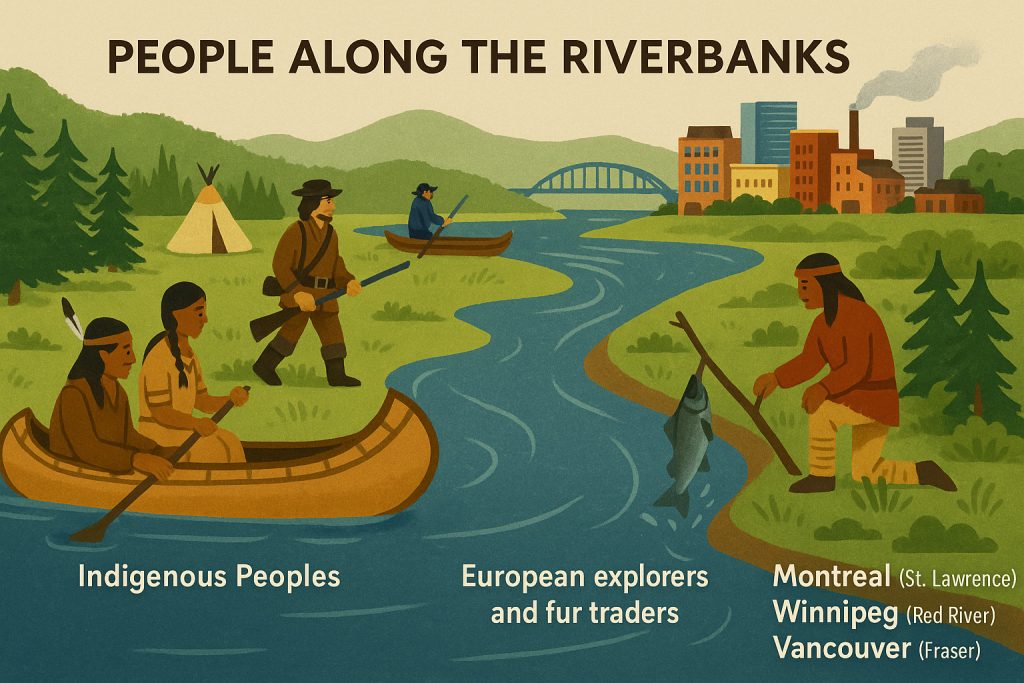

👣 People Along the Riverbanks

Long before roads or railways, rivers were the original highways of what is now Canada. For thousands of years, Indigenous Peoples such as the Cree, Dene, Haida, Mi’kmaq, Anishinaabe, Innu, and Tlingit built their lives around these waters. Rivers were—and still are—sources of food, transportation, spiritual meaning, and seasonal rhythm.

🛶 Indigenous Lifeways and River Cosmologies

In Indigenous worldviews, rivers are not just physical entities—they are living beings, ancestral spirits, and sacred paths. The Fraser River is central to many Coast Salish nations, not just for its salmon runs, but for its place in creation stories. Along the Mackenzie, the Dene people once paddled for weeks to reach seasonal fishing camps. In Mi’kma’ki (eastern Canada), rivers served as migration routes and links between summer coastal sites and winter forest settlements.

Canoes, carved from cedar or birchbark, were expertly crafted to match local river conditions—whether swift alpine flows or slow, winding boreal channels. Traditional knowledge passed down through generations helped communities read the rivers: their eddies, levels, moods, and offerings.

🧭 Explorers, Fur Traders, and Colonization

With the arrival of Europeans, rivers became arteries of expansion and exploitation. French voyageurs paddled the Ottawa River and St. Lawrence deep into the interior in search of beaver pelts, relying heavily on Indigenous guides and knowledge. The Red River became a vital corridor for the Métis Nation, whose culture fused European and Indigenous traditions along these waterways.

Rivers were the backbone of the fur trade, which gave rise to powerful commercial empires like the Hudson’s Bay Company. Trading posts, and eventually cities, grew along major river junctions.

🏙 Urban Growth and Industrialization

By the 19th and 20th centuries, rivers powered the rise of industry. Mills, shipyards, and railways clustered on riverbanks, fueling economic growth—but often at the cost of ecological health. Montreal flourished on the St. Lawrence, Vancouver on the Fraser, and Winnipeg on the Red River, each leveraging the river for shipping, fishing, agriculture, and energy.

Even today, rivers remain cultural and recreational centers—places for festivals, canoe races, waterfront parks, and renewal. Yet many communities, especially Indigenous and rural ones, still face access, pollution, and water justice issues.

Canada’s rivers are more than geological features—they are human histories, lifelines, and living memory. Along their banks, languages were spoken, treaties signed, rebellions fought, and songs sung. The story of Canada is in many ways the story of the people who have lived beside and been shaped by its rivers.

⚠️ Threats and Conservation Challenges

Though Canada is home to some of the cleanest and most powerful rivers on Earth, these lifelines are increasingly under siege. Once seemingly eternal and invincible, many waterways now face the slow unraveling of ecological health. Human activity, climate instability, and resource extraction are testing the resilience of river systems that have flowed for millennia.

⚡ Hydroelectric Dams: Power vs. Passage

Canada is one of the world’s top producers of hydroelectricity, with over 500 major dams harnessing rivers for energy. While they provide low-emission power, these dams come at a cost: they block migratory fish, alter sediment flows, submerge forests, and fragment ecosystems. Iconic rivers like the Columbia, Churchill, and Nelson have been transformed by concrete walls that drown rapids, reroute currents, and silence waterfalls.

🧪 Pollution: A Hidden Contaminant

From fertilizers in the Prairies to industrial discharges near urban centers, pollution seeps into rivers across Canada. Nitrate runoff, heavy metals, and untreated sewage degrade water quality, harm aquatic life, and compromise drinking water—especially in First Nations communities, where boil-water advisories remain a stark reality. In southern rivers, algal blooms and oxygen-depleted zones are becoming more common, a warning sign of ecological stress.

🌡 Climate Change: Disrupting the Rhythm

Rivers are shaped by rhythm: snowmelt in spring, low flows in summer, freeze in winter. Climate change is unraveling that pattern. Glaciers feeding rivers like the Bow, Fraser, and Mackenzie are shrinking fast, reducing long-term water supplies. Warmer winters shorten ice cover, while more extreme floods and droughts swing rivers between extremes. Fish spawning cycles, aquatic insect hatches, and wetland ecosystems all struggle to adapt.

⛏ Extractive Industries: Draining the Wild North

Canada’s boreal and sub-Arctic rivers remain some of the last free-flowing giants on Earth—but they are not untouched. Mining, logging, oil and gas extraction, and even water bottling operations pose risks to pristine northern watersheds. Roads, tailings ponds, and pipeline corridors can disrupt hydrology, introduce toxins, and fracture Indigenous lands where water is not just resource—but relative.

🌱 Rising Guardianship: A Current of Hope

Yet not all is loss. Across Canada, a wave of river conservation is gaining momentum:

- Indigenous-led stewardship projects are reviving ancient care systems—from the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council to land guardians along the Peel River Basin, where a landmark court decision protected over 55,000 km² of wilderness.

- Restoration efforts, like those on the Nottawasaga, Kettle, and Fraser, are replanting riparian zones, removing dams, and restoring spawning grounds.

- Citizen science, watershed councils, and local activism are pushing back against degradation, calling for legal rights for rivers and better water governance.

Rivers cannot speak, but their health—or decline—says everything. Protecting them is no longer optional—it is the most urgent form of climate action, cultural respect, and planetary repair we can undertake.

🌎 Conclusion: Canada’s Wild Lifelines

Canada’s rivers are more than just watercourses—they are threads in the nation’s ecological, cultural, and spiritual fabric. From icy Arctic deltas to the salmon-charged rapids of the west coast, these rivers flow through time and space, telling stories of glaciers, people, and resilience. Protecting them isn’t just an environmental act—it’s a promise to future generations that this vast, wild beauty will endure.

🛶 Want to learn more? Explore our upcoming series on North America’s Greatest Rivers—next stop: the mighty Yukon.