The Living River: How Natural Dynamics Shape Biodiversity

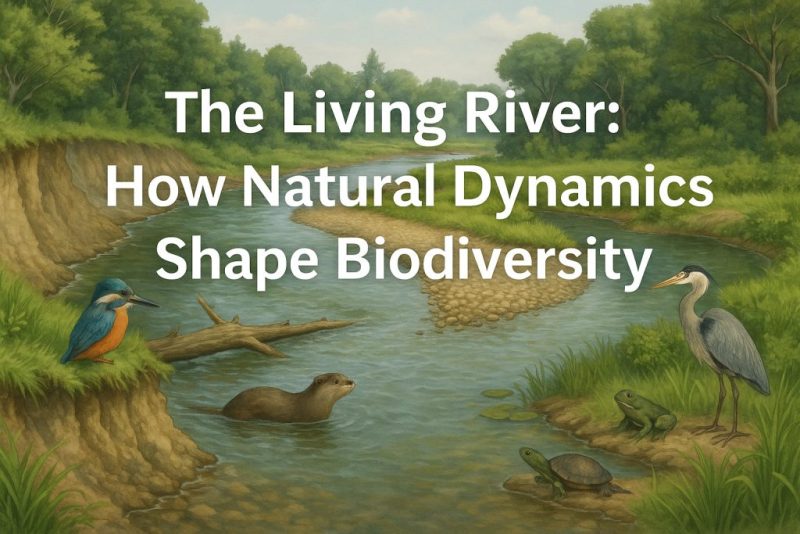

Natural rivers support rich biodiversity by constantly renewing themselves and creating diverse habitats for plants and animals to thrive.

Natural rivers are lifelines of biodiversity, not just channels of water. Their ever-changing flow patterns, seasonal floods, and free-moving channels shape a mosaic of habitats—pools, wetlands, gravel bars, and floodplains—each supporting unique communities of plants and animals. As the river shifts course, it renews old habitats and creates new ones, offering refuge, breeding grounds, and feeding zones for countless species. This dynamic process is essential for the resilience and richness of ecosystems, making natural river dynamics a cornerstone of biodiversity conservation.It’s easy to see that a regulated river—with artificial banks, no riparian vegetation, and missing features like gravel bars, steep banks, and side branches—supports far less life. Even so-called “light” regulation, which leaves a thin layer of greenery along the banks, only offers a pale shadow of the rich biodiversity found in truly natural rivers.

Natural vs. Regulated Rivers: A Stark Contrast in Biodiversity

When comparing natural rivers to their regulated counterparts, the difference in biodiversity is striking. Natural rivers flow freely, meandering through the landscape, carving out new channels, forming gravel bars, steep banks, oxbows, and side branches. These features create a diverse mosaic of microhabitats, supporting everything from spawning fish and amphibians to birds, insects, and riparian plant communities. Dense vegetation along the banks not only stabilizes the soil but also offers shade, food, and shelter for countless species.

In contrast, regulated rivers are often stripped of life. With artificial banks, channelized flows, and engineered barriers, they lack the complexity that nature builds over time. Riparian zones are often absent or reduced to a narrow strip of uniform greenery, unable to support the same variety of organisms. Even when some vegetation is allowed to remain, it represents only a fragment of the richness found in untouched systems. Floodplains are cut off, sediment no longer moves naturally, and seasonal dynamics are muted—all of which erode the ecological integrity of the river system.

In short, regulation simplifies, while natural dynamics diversify. And in the world of ecology, diversity means resilience, function, and life.

Learn more about other negative aspects of river regulation.

The Self-Renewing Power of Dynamic Rivers

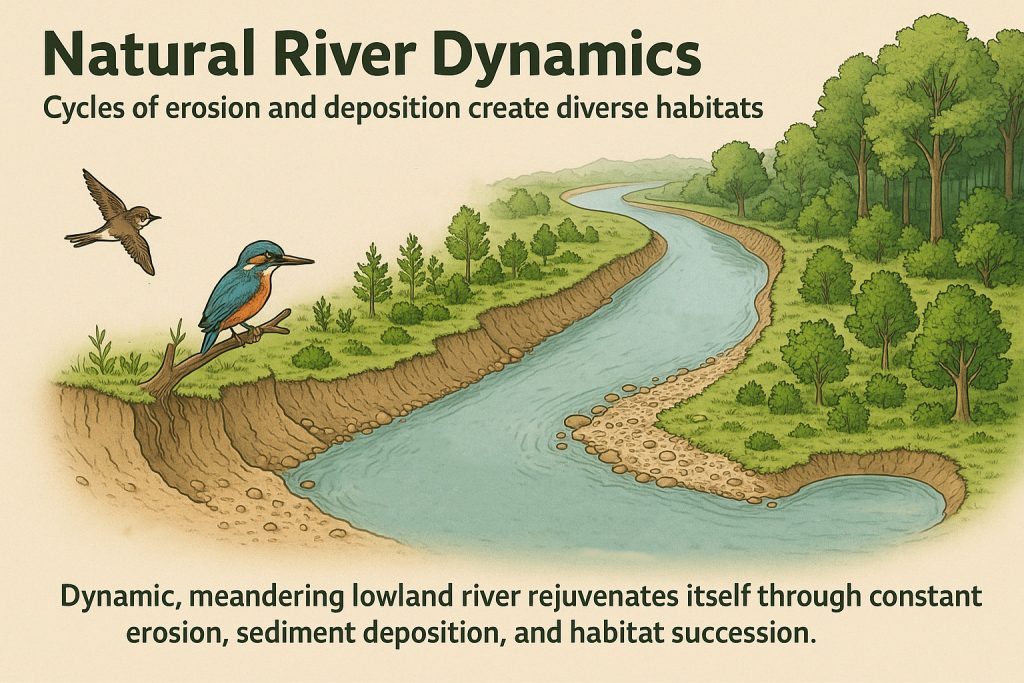

A dynamic river, especially in lowland regions where meandering is most prominent, is a living system in constant renewal. Its secret lies in the cyclical processes of erosion and sediment deposition—a natural rhythm that acts as the river’s fountain of youth.

Unlike regulated rivers, which often display a static landscape of mature forest and simplified habitats, natural rivers showcase the full spectrum of ecological succession. On these vibrant floodplains, you’ll find everything from bare gravel and sand bars, steep banks to dense young forests, all coexisting within a single river corridor.

The process begins with erosion on one bank and sediment deposition on the other. Steep, freshly cut banks are continually created or reshaped—valuable nesting sites for birds like kingfishers andsand martins. Meanwhile, sediment is deposited as gravel and sand bars, not only carried from upstream but also eroded locally from the riverbanks. These exposed bars are the first footholds for plant life. Pioneer species take root, stabilizing the substrate and capturing finer silt. Over time, these sites evolve into grassy patches, then into shrubs, followed by dense young forests, and finally, if undisturbed, into mature woodland. Each stage along this path supports its own distinct community of plants, insects, birds, and mammals, adding layers of biodiversity to the river landscape.

At the same time, the river itself is shifting its course. It may create new side channels or reclaim ancient depressions, forming flowing sidearms. As it meanders more dramatically, it often cuts off loops, leaving behind oxbow lakes—crescent-shaped waterscapes that gradually fill with sediment and organic matter. These backwaters undergo their own slow aging process, evolving from open water habitats to lush wetlands, and eventually, in both tropical and temperate climates, becoming forested floodplain habitats.

This continuous reshaping means that a natural river is always in flux. It carves, deposits, meanders, and floods—constantly resetting the landscape, restarting succession, and creating new opportunities for life to flourish. This perpetual rejuvenation is what makes dynamic rivers not just beautiful but ecologically irreplaceable.