Floodplains: As Vital as the River Itself

Floodplains, once overlooked, are vital extensions of rivers—hydrologically linked, ecologically rich, yet often severed or lost to development.

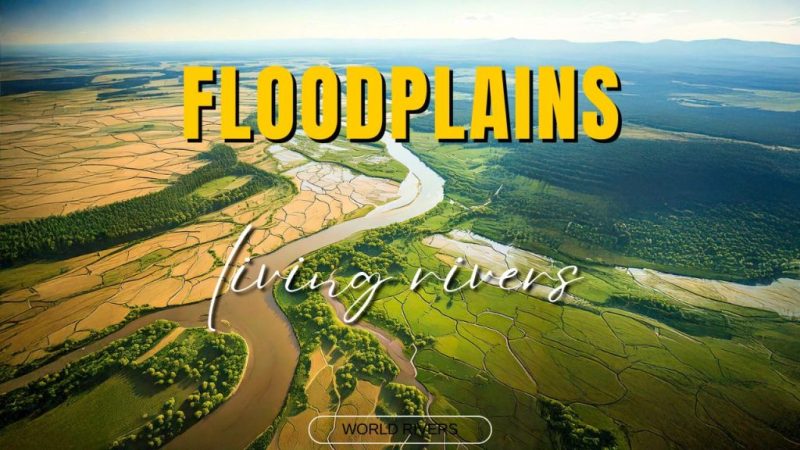

A floodplain is a wide, flat expanse of land formed over time by the gradual build-up of sediment on either side of a stream channel. These low-lying areas come alive during floods, when rushing water spills beyond the riverbanks, spreading across the plain and carrying with it suspended silt and clay. As the waters recede, they leave behind a thin, horizontal blanket of fine sediments, enriching the soil and reshaping the landscape in subtle but powerful ways. Floodplains are extremely important parts of the lowland rivers.

Floodplains: Sculpted by Time and Flow

Floodplains are not static landscapes—they’re in a constant state of transformation. Especially in lowland, meandering rivers, the floodplain is continuously eroded and reshaped by the restless flow. What emerges is often a mosaic of side-arms and dead-arms, like oxbow lakes, silent witnesses to the river’s changing path.

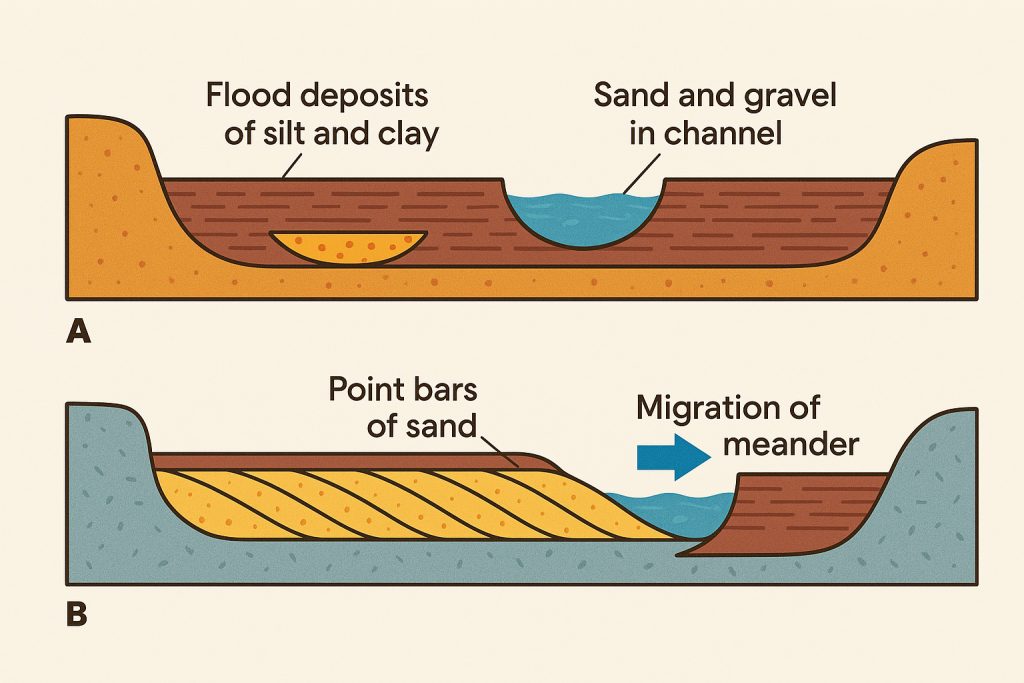

Some floodplains form almost entirely from horizontal layers of fine-grained sediment, gently laid down by retreating waters. Others are shaped by sinuous meanders that wander across the valley floor, carving out new paths and leaving behind point bars on the inside bends. These rivers create a distinctive fining-upward sequence—a natural record of their dynamic life. At the base lie coarse channel deposits, covered by medium-grained point bar sands, and finally capped by fine-grained silts and clays from floodwaters. It’s a layered archive, each stratum telling a story of flow, erosion, and quiet deposition.

The Slowing Surge and the Rise of Natural Levees

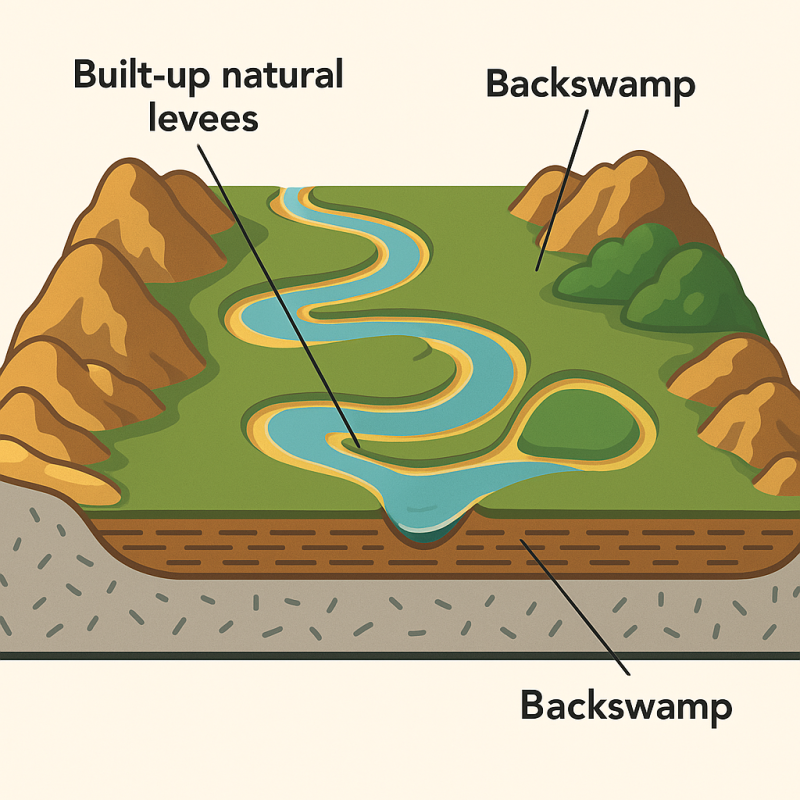

As floodwaters spill from a river onto the floodplain, their momentum falters. Friction with the flat valley floor slows the flow dramatically, transforming the swift, channeled current into a thin, sprawling sheet of water. This abrupt loss in velocity prompts the river to drop its sediment load, starting with the heaviest particles closest to the main channel.

Over time, repeated flooding builds up natural levees—subtle ridges of sediment that flank the riverbanks, gently sloping away from the channel. These elevated borders influence the behavior of tributaries, sometimes forcing them to run almost parallel to the main river for a stretch, rather than merging directly. It’s one of the many quiet ways that sediment and water collaborate to shape the land.

Not All Floodplains Are Created Equal

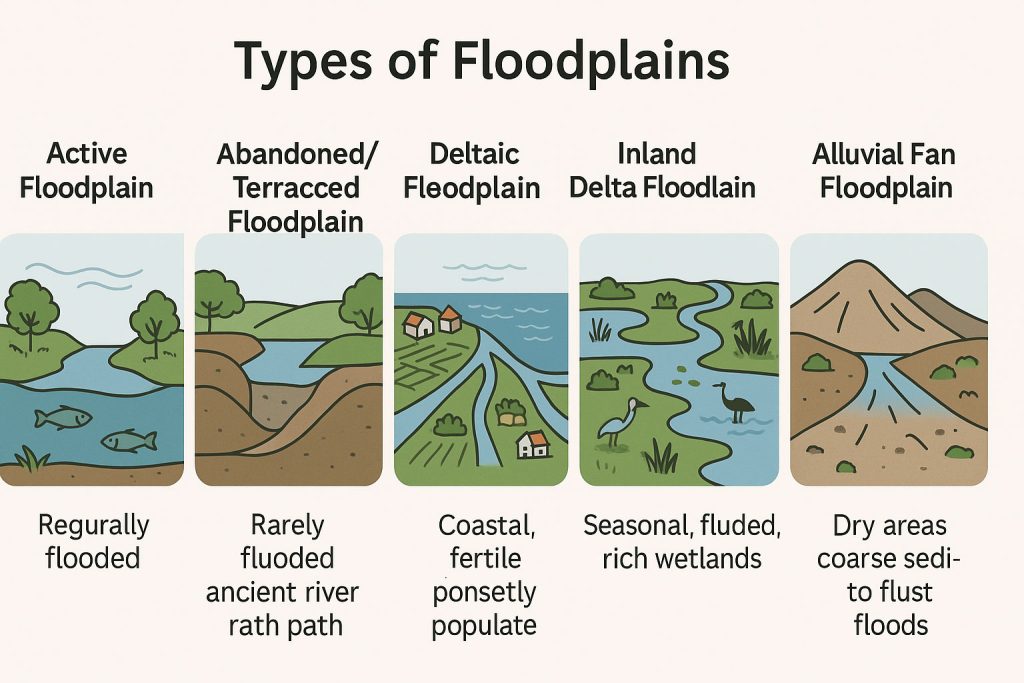

Though the word floodplain might evoke a single image—wide, grassy stretches beside a lazy river—these dynamic landscapes come in a surprising variety of forms, each sculpted by time, flow, and topography. Understanding their differences helps us appreciate the diverse roles they play in ecosystems and human life.

-

Active Floodplains

These are the most dynamic and vibrant. Actively shaped by regular flooding, they lie directly adjacent to the river channel and are frequently inundated, especially during seasonal high flows. Active floodplains are biologically rich, home to migrating fish, breeding birds, and flood-adapted plants. Examples include parts of the Amazon Basin and Lower Mekong. -

Abandoned or Terraced Floodplains

Once part of the active river system, these areas have been left behind as the river shifted its course over time. They often appear as terraces, elevated slightly above the current river channel, and are flooded only during extreme events. Though quieter in terms of hydrology, these floodplains can store old river sediments and support agriculture or grasslands. -

Deltaic Floodplains

Found at river mouths where the river meets a standing body of water (like an ocean or lake), deltaic floodplains are shaped by sediment deposition and tidal influence. Think of the Nile Delta, Mississippi Delta, or the intricate Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta—all lush, fan-shaped floodplains that are densely populated and agriculturally vital, yet highly vulnerable to sea level rise. -

Inland or Inland Delta Floodplains

These occur where rivers dissipate into the land rather than the sea, creating vast seasonal wetlands. The Okavango Delta is a prime example—a floodplain without an ocean, where the river’s life-giving pulse vanishes into the sands of the Kalahari Desert. -

Alluvial Fan Floodplains

Less common but visually striking, these occur where steep mountain streams flatten out and spread sediments in a fan shape. The resulting floodplain is often coarse-grained and prone to flash flooding. They’re found in arid or semi-arid regions, such as parts of California or Central Asia.

Each type plays a unique role—some teem with wildlife, others feed cities and farms, and many act as natural shock absorbers in a changing climate. Regardless of form, all floodplains remind us that rivers are not lines, but living systems with breadth and breath.

The Living Heart of the River

The floodplain is a landscape of quiet contrasts. Closest to the river, the sediment is coarser—sands and silts dropped quickly as the waters slow. But farther out, where the flood spreads thin across the land, it leaves behind a delicate layer of fine clay, enriching the lowlands with fertile soil.

Yet floodplains are more than just sediment sinks—they are biological powerhouses. In many regions, they are even more productive than the river itself. The still backwaters that form in these plains become vital nurseries for fish, amphibians, and countless other species, nurturing biodiversity that supports both ecosystems and local livelihoods.

Despite their importance, floodplains have long been neglected, drained, or cut off in favor of rigid river control. The historical focus on deepening and straightening main channels has come at a cost. Today, we’re finally recognizing that an active, connected floodplain is just as critical as the riverbed itself—especially during rising floods and extreme weather.

In modern water management, floodplains act as natural reservoirs, absorbing vast volumes of water during flood events. This essential role in flood defense is just one of many ecosystem services they provide, from supporting biodiversity and groundwater recharge to carbon storage and fertile agricultural land. Floodplains are not just edges of rivers—they’re the lungs, the womb, and the memory of the riverine world.

Floodplains: Vast, Vital, and Often Overlooked

Floodplains stretch far beyond what the eye can see—sprawling across nearly 2.9 million square kilometers of Earth’s surface. That’s almost the size of India. These dynamic landscapes form along rivers large and small, shaping ecosystems, cultures, and civilizations throughout history.

Some of the world’s most iconic floodplains have become synonymous with abundance and life. The Amazon floodplain, for instance, is an ever-shifting mosaic of forest and water. It swells by up to 10 meters during the rainy season, flooding vast areas and creating one of the richest habitats on the planet. Meanwhile, the Okavango Delta in Botswana—technically an inland floodplain—transforms the dry Kalahari Desert into a lush oasis, teeming with elephants, lions, birds, and fish in a miraculous seasonal pulse.

Closer to human history, the Nile floodplain gave birth to Ancient Egypt. Its predictable annual floods deposited nutrient-rich silt, making agriculture possible in an otherwise arid land. In Europe, the Danube’s floodplains—particularly in Hungary and Serbia—are among the last semi-natural ones on the continent, hosting rare birds and offering crucial wetland functions.

Threats to the floodplains

But not all floodplain stories are thriving. Globally, over 90% of floodplains in industrialized regions have been altered, disconnected, or urbanized. Channelization, dams, levees, and agricultural expansion have diminished their role in flood regulation and biodiversity support. What remains is a fraction of their former reach, yet their value has never been more critical.

Hydropower dams dramatically reshape river systems, both upstream and downstream. By blocking the natural flow of water, they transform free-flowing rivers into artificial reservoirs, altering water temperature, sediment transport, and oxygen levels. Downstream, the reduced sediment flow can lead to riverbed erosion, collapsing riverbanks and diminishing fertile floodplains. The seasonal rhythms of flooding—essential for many ecosystems—are disrupted, often eliminating wetlands and backswamps. For migratory fish like salmon, dams become insurmountable barriers, fragmenting habitats and threatening entire populations. While hydropower offers renewable energy, its ecological cost on river dynamics and biodiversity is profound.

Today, as we face increasing climate extremes, floodplains are being reimagined not just as wild, fertile spaces, but as essential buffers against disaster—natural infrastructure for a warming world. Restoring them is not just about conservation—it’s about rebalancing our relationship with rivers and recognizing the quiet, powerful work these landscapes do every flood season.