Albania Rivers: Wild Beauty Under Threat

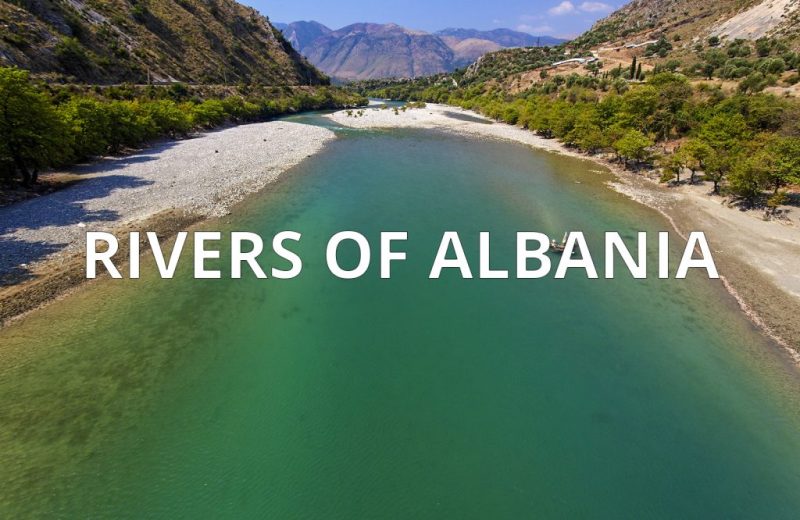

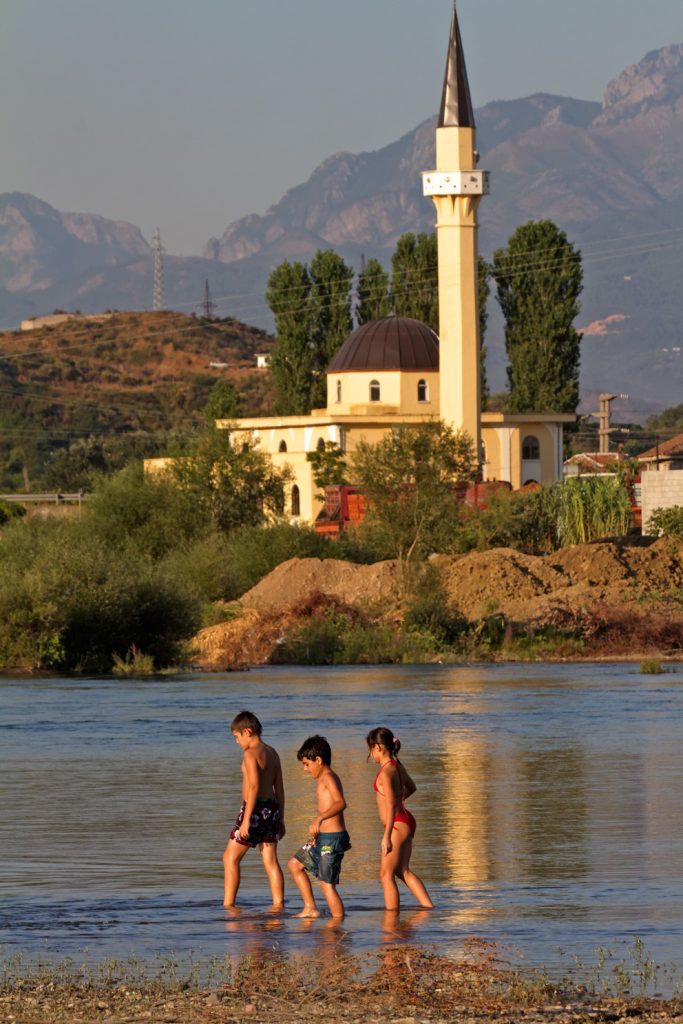

Albania rivers tumble from mountains to the Adriatic—wild, untamed, and now at risk as dam projects threaten their flow, life, and future.

Albania, a small country nestled in the heart of the Balkan Peninsula, is a land carved by water. Known for its dramatic landscapes, it’s home to a network of rivers, streams, springs, and some of Europe’s most iconic lakes—like the vast Lake Shkodër, the deep, ancient Lake Ohrid, and the twin jewels of the Prespa basin. Explore Albania rivers!

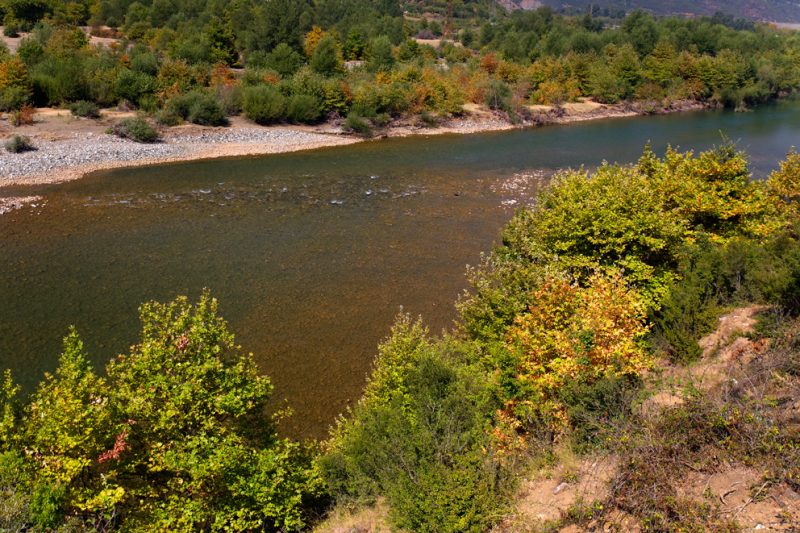

Often called “the land of the eagle,” Albania rises sharply into rugged mountains and rolling hills that slice across the country in all directions. From these highlands, rivers are born—rushing westward through deep valleys before reaching the Adriatic Sea. Though short in length, these rivers are vibrant, untamed, and represent some of the finest examples of natural river stretches in Europe.

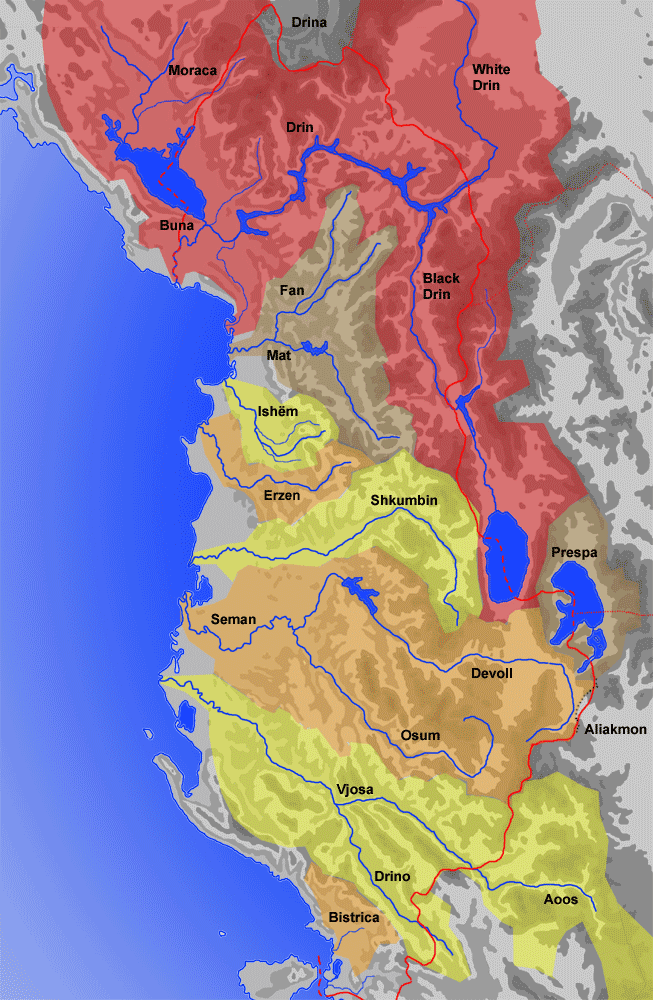

Where the Water Stays: Albania’s Self-Contained River System

The rivers of Albania carry a total annual flow of 1,308 m³/s, amounting to an impressive 41.25 km³ per year. Remarkably, the vast majority of precipitation that falls on Albanian soil remains within the country’s borders—draining through rivers that carve westward to meet the Adriatic Sea.

In fact, Albania is almost a closed hydrological system. To the north, only a small stream slips across the border. To the south, a tiny rivulet drains into Greece. The rest flows entirely within, making Albania’s rivers unique hydrological corridors that define the country’s natural rhythm and identity.

Carving the Land: Albania’s Canyons, Valleys, and Waterfalls

In their upper courses, Albania’s rivers slice through the high mountain ranges, forming deep valleys and dramatic gorges—some with near-vertical walls soaring up to 90 meters (300 feet) above the water. The result is a raw, untamed beauty that feels almost mythical.

The Valbona River, with its turquoise waters, white pebbles, snow-capped peaks, and rushing rapids, delivers postcard-perfect Alpine landscapes. Elsewhere, nature sculpts the land into marvels like the Shala Valley in the Northern Alps, the Tomorica Valley, Këlcyra Gorge on the Vjosa River, and the stunning Bënça and Osumi Canyons. These canyons, with their sheer rock faces and winding waterways, create an ideal playground for rafting, kayaking, and other river sports.

Many of these rivers have also become sites for hydropower development, feeding large dams that supply a significant portion of Albania’s electricity. Yet, the rich karst landscape—marked by porous limestone and underground flows—makes irrigation mostly limited to the valley floors.

Sprinkled throughout this wild terrain are waterfalls—like those of Grunas, Thethi, Shoshan, and Kurveleshi—which add to the region’s natural wonder. Over 200 springs gush from the earth to feed tributaries and provide clean, drinkable water to nearby communities. Some are even thermal springs, long revered for their healing properties since ancient times.

Where Rivers Meet the Sea: From Braided Streams to Coastal Deltas

As Albania’s rivers descend from the mountains, they enter their middle courses, where the terrain softens and the rivers begin to meander. Here, many adopt a braided form, their sediment-laden beds spreading into shifting channels. Rivers like the Devolli, Vjosë, and Mati are vivid examples of this dynamic phase—constantly reshaping their paths with each flood and season.

Eventually, these rivers reach the Adriatic Sea, often ending in small, fan-shaped deltas, especially along the low and sandy Adriatic coast. These fertile fringes are where river and sea embrace, creating alluvial plains rich in biodiversity and agricultural potential.

In contrast, the Ionian coast to the south is mostly rugged and mountainous, with steep cliffs plunging into deep blue waters. Here, only a few rivers carve their way through narrow gorges to reach the sea.

Among the most remarkable coastal landscapes is the Plain of Myzeqe—an expansive alluvial plain shaped by three mighty rivers: the Shkumbin, the Seman, and the Vjosë. This fertile region, etched over millennia by flowing waters, tells the final chapter of Albania’s river journey—from mountain spring to ocean mouth.

🗺️ The Major Rivers of Albania: A Wild Network Still Flowing Free

Albania’s river system is woven from a network of 11 major rivers and over 150 tributaries, coursing through mountains, valleys, and coastal plains. This hydrological tapestry is not just extensive—it’s exceptionally wild by European standards.

The most prominent rivers include the Drin River in the north, Albania’s longest and most voluminous, and the Seman and Shkumbin Rivers in the south, which help define the fertile lowlands.

Remarkably, even some of the largest river systems—such as the Vjosa, the Seman with its Devoll and Osam tributaries, and the Shkumbin—remain largely undammed, flowing freely from source to sea. These untouched stretches represent some of the last wild rivers in Europe and are critical strongholds for biodiversity, ecological integrity, and sustainable livelihoods.

The Drini River: Albania’s Powerhouse of Water and Energy

The Drini River, Albania’s most important watercourse, is formed by two major tributaries: the Black Drini, which rises in North Macedonia and drains a catchment of 5,885 km², and the White Drini, which flows from Kosovo. Together, they unite to form a river system that is not only hydrologically significant but also economically vital.

Along its course, the Drini hosts three large hydroelectric power plants, with a combined water storage volume of 3,730 million m³. These dams provide a staggering 93% of Albania’s electricity generation capacity, making the Drini a true lifeline of national energy.

As it flows northwest, the Drini merges with the Buna River near Shkodra. The Buna, in turn, drains Lake Shkodra, which straddles the border with Montenegro and is fed by rivers from both countries, including the significant Morača River.

Historically, the Drini and Buna once had separate outflows to the sea. Today, however, most of the Drini’s water is funneled into the Buna River, with only a small portion still following the Drini’s original southern channel toward Lezha. The unified flow now continues along the Montenegrin border, ultimately reaching the Adriatic Sea near Ada Bojana—a branching river delta that’s become a naturist paradise known for its unique ecosystem and wild beaches.

🌾 The Seman River: Heart of Albania’s Inland Waters

The Seman River boasts the largest drainage basin entirely within Albania, making it a key artery of the country’s hydrological and agricultural systems. It is formed in the lowlands by the confluence of two major rivers: the Devoll, stretching 160 km from the north, and the Osum, flowing 113 km from the south.

From this union, the Seman winds westward in a series of broad meanders for about 80 km, eventually reaching the Adriatic Sea near the Karavasta Lagoon—a biologically rich coastal wetland and one of the largest lagoons in the Mediterranean. (Note: Tropojë is inland and unrelated to the Seman outflow—likely a mix-up with another location.)

In ancient times, the Seman was known as the Apsus River, marking its presence in classical texts and trade routes.

Today, modern infrastructure meets ancient flow. On the Devoll River, a hydropower and irrigation dam was recently constructed at Banja by Italian developers—part of an expanding effort to harness Albania’s rivers for both energy and agriculture. While the main course of the Seman remains undammed, its tributaries are increasingly shaped by such interventions.

The Shkumbin River: A Cultural and Natural Boundary

Rising in the Valamara Mountains of southeastern Albania, the Shkumbin River flows for 112 miles (180 km) before emptying into the Adriatic Sea. Along its course, it is fed by important tributaries, including the Gur i Kamjës and Rapun streams, adding volume and vitality as it cuts across central Albania.

But the Shkumbin is more than just a river—it is a historical and cultural divide. For centuries, it has marked the linguistic boundary between the Gheg and Tosk dialects of the Albanian language. In ancient times, it also delineated the edge of the Epirus region, standing as the cultural frontier between the Greek and Illyrian worlds during the 5th and 6th centuries.

This river is a natural corridor of both water and identity, flowing through landscapes shaped by history, myth, and the enduring rhythms of daily life.

The Vjosë River: Europe’s Last Wild River

The Vjosë River is one of the last truly wild rivers in Europe—untamed, free-flowing, and breathtakingly beautiful. Stretching 272 kilometers from its source in northwestern Greece to the Adriatic Sea in southwestern Albania, the river flows uninterrupted through a tapestry of canyons, gorges, and fertile valleys.

The first 80 kilometers wind through Vikos–Aoös National Park, where the river cuts deep into the landscape, forming dramatic canyons near Konitsa. Crossing into Albania at Çarshovë, the Vjosë continues its journey northwest, passing through a string of towns that feel like milestones in a flowing odyssey: Përmet, Këlcyrë, Tepelenë, Memaliaj, Selenicë, and Novoselë—before finally spilling into the Adriatic Sea just northwest of Vlorë.

More than just a geographical feature, the Vjosë has become a symbol—a battleground for conservation in the Balkans. Its Albanian stretch is a river of extraordinary ecological value, home to rich biodiversity, traditional communities, and natural processes untouched by large-scale development.

Today, the Vjosë stands at the heart of a growing movement to protect Europe’s last wild rivers from the rising tide of hydropower dam projects. In its roaring waters, people see not only beauty—but resistance.

The Valbona River: Wild Waters of the Unconquered North

The Valbona River winds through the Valbona Valley, a breathtaking slice of the Albanian Alps in the Tropoja District of Northern Albania. This crystal-clear river gives its name not only to the valley, but also to the surrounding region and a small village nestled within it. Everywhere it flows, it brings with it the spirit of the north—untamed and deeply rooted in tradition.

Set against the dramatic backdrop of the Accursed Mountains (Bjeshkët e Nemuna), the Valbona River flows through a land known as the Malësi—a highland region inhabited by strong, fiercely independent people. For over two millennia, these mountains have sheltered a culture that resisted conquest, from Roman legions to Ottoman armies.

The Valbona Valley is more than just a natural wonder—it’s a living symbol of Albania’s rugged heart, where glacial waters, alpine meadows, and stone-built homes exist in harmony with ancient traditions. Today, it’s one of the country’s most beloved hiking and eco-tourism destinations, drawing travelers into its wild, untouched embrace.

Under Siege: The Growing Threats to Albania’s Rivers

For nearly half a century, Albania was sealed off from the world, cloaked in communist isolation. During this time, its natural wonders—from soaring mountains to turquoise rivers—remained hidden, protected not by intention, but by circumstance. While the regime stifled freedoms, it also limited unchecked development. Yet, even under centralized rule, the government undertook large-scale infrastructure projects, including the construction of massive hydropower dams that altered the course of many rivers.

Still, many rivers remained untouched—wild, free, and forgotten.

With the fall of communism and the country’s reopening to the world, came a new wave of pressure. Foreign investors, lured by Albania’s untapped natural wealth, began to see opportunity where others saw ecological treasure. This story echoes across the Balkans, where wild rivers are rapidly being transformed into sources of profit, often at the expense of ecosystems and local communities.

Today, a coalition of organizations—WWF, Euronatur, and Riverwatch—is fighting to protect the last free-flowing rivers of the Balkans. Their flagship effort centers on the Vjosë River, but other gems like the Seman and Shkumbin Rivers still flow uninterrupted—for now.

Albania’s rivers stand at a crossroads: preserve their wild beauty, or surrender them to the relentless current of development. The world is watching. The choice is urgent.

See the gallery: