How Sediment Deposition Shapes River Landscapes

Sediment settles as river energy fades, forming bars, banks, and floodplains. This quiet process plays a vital role in shaping ecosystems and terrain.

Table of Contents

Toggle

Alongside erosion and sediment transport, sediment deposition plays a crucial role in shaping river landscapes and forming new habitats, helping to sustain rich biodiversity.

The sediments transported by a stream are often deposited temporarily along the stream’s course (mainly the bed load sediments). Such sediments move sporadically downstream in repeated cycles of erosion and deposition, forming bars and floodplain deposits. At or near the end of a stream, sediments may be deposited more permanently in a delta or an alluvial fan.

Sand and Gravel Bars

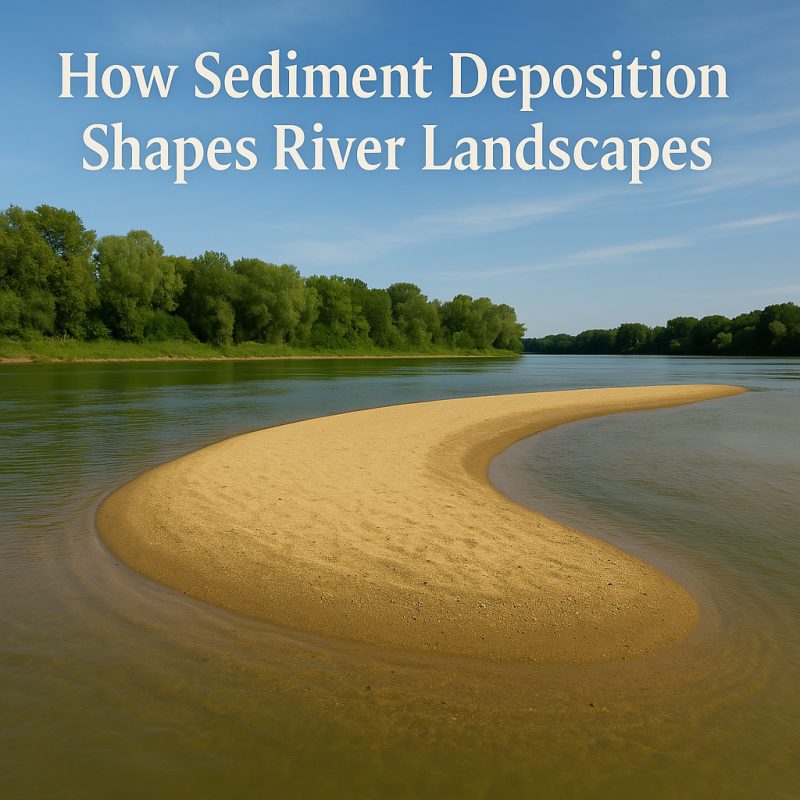

Stream deposits often appear as bars—ridges of sediment, typically composed of sand, gravel, or both. These bars form either in the middle of the stream or along its banks, emerging where the water’s velocity slows and it can no longer carry its full sediment load. In meandering rivers, point bars develop on the inside bends of curves, where the current is slower and deposition dominates.

During a flood, a river becomes a powerful transporter of sediment—capable of moving everything from fine silt and clay to massive boulders. The surge in water volume and velocity gives the river the energy needed to lift and carry even the heaviest particles. But as the floodwaters begin to recede, the river’s energy fades. The water level drops, its speed slows, and it can no longer support the weight of all the suspended material.

The largest boulders are the first to settle, dropping onto the streambed and further slowing the current in that area. This creates a calm zone where finer gravel and sand begin to settle, filling the gaps between larger stones and forming the foundation of a gravel and sand bar—often revealed as the water continues to fall.

Nature’s Anchors: How Obstacles Shape Sediment and Spark New Life

Sometimes, a fallen tree or other obstacle becomes the nucleus for a bar’s formation. These objects disrupt the flow, generating eddies—circular currents where water swirls and loses energy. In these eddies, sediment accumulates, often forming a long, tapering tail of deposition downstream of the obstruction. Here, finer materials like sand and silt settle—rich in nutrients and often fertile enough to support the growth of pioneering plants. These roots, in turn, help stabilize the sediment.

When the next flood comes, it may scour much of the bar away, carrying sediment further downstream. Yet as the waters slow again, new gravel often deposits in the same general area, and a new bar begins to form. Over time, with each flood pulse, these bars shift in shape and size—constantly reshaping the river’s course and creating new habitats in the process.

The braided streams are wider riverbeds where the water is flowing in several channels through the sediment. It is common for middle stretches of the rivers. Learn more here.

Sand and Gravel Bars: Cradles of Life in a Shifting Riverbed

Sand and gravel bars are far more than static piles of sediment—they are living landscapes in motion. These bars emerge where the river slows, depositing its load of sand, gravel, and finer particles. What begins as a bare ridge of sediment soon becomes a dynamic habitat, offering refuge, shelter, and breeding grounds for a wide range of aquatic and terrestrial species.

With time, pioneer plants take root in the moist, nutrient-rich substrate. Their presence marks the beginning of vegetation succession, a gradual greening of the bar as roots stabilize the soil and create microhabitats for insects, amphibians, birds, and more. What was once a patch of bare sediment evolves into a vibrant, self-sustaining ecosystem, constantly shaped and renewed by the rhythm of floods and flows.

Placer Deposits: Nature’s Hidden Treasure Troves

Placer deposits form in streams where flowing water mechanically concentrates heavy sediment. This occurs in zones where the velocity of water is high enough to carry away lighter particles, but not the denser ones, allowing heavier materials to settle out.

Typical locations include river bars on the inside of meanders, plunge pools below waterfalls, and depressions on the streambed—areas where the current briefly slows or swirls, losing the energy needed to keep heavier grains in motion.

These deposits often contain gold dust and nuggets, native platinum, diamonds, and other precious gemstones, as well as heavy mineral grains rich in titanium and tin oxides. Because of this, placer gold deposits have historically attracted countless gold panners, fueling gold rushes and shaping entire regions.

What begins as a natural sorting process becomes a concentrated pocket of wealth, making placer deposits both geologically intriguing and economically valuable.