Rivers That Disappear in the Continents: Endorheic and Lost Rivers Explained

Most rivers flow to the sea—but some vanish inland. Discover rivers that disappear in the continents: endorheic basins, lost rivers, and inland deltas.

Rivers that disappear in the continents may sound like something out of a legend—but they are very real, and surprisingly common. While most rivers dutifully follow gravity’s call to the sea, some never make it. These rivers vanish within the landmass itself, either seeping into porous karst landscapes, evaporating in sun-scorched basins, or spreading into vast inland deltas that fade into silence. Known as endorheic rivers, they flow into closed drainage systems with no outlet to the ocean.

Some end up in the lakes, some disappear underground through karst sinkholes as the lost rivers, or dry up into ghostly traces across deserts and steppes. These enigmatic waterways reveal a hidden geography where water doesn’t follow the rules—and where the continent, not the sea, becomes the final destination.

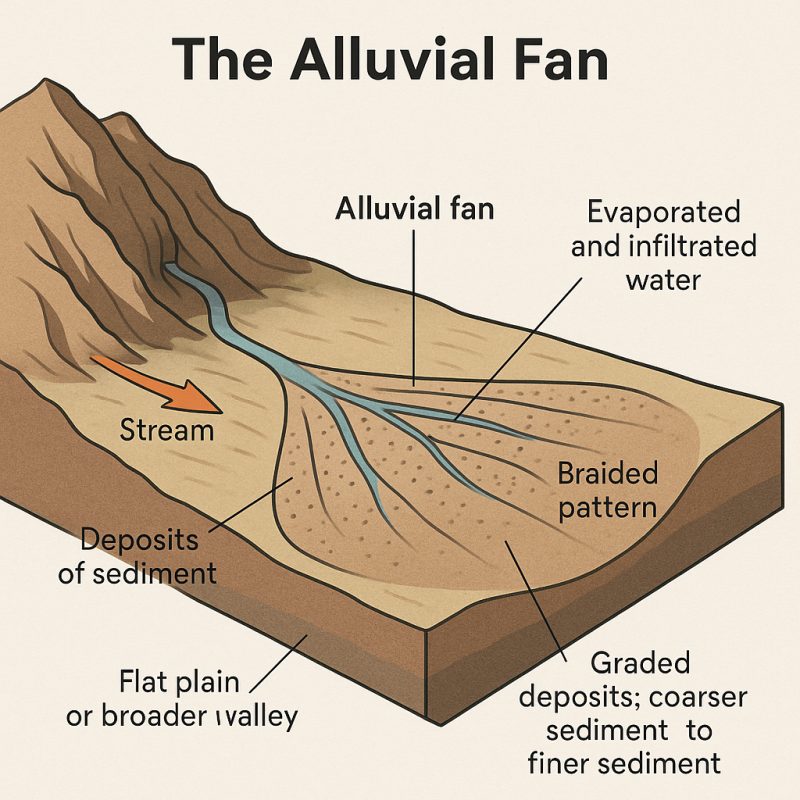

🌾 The Alluvial Fan

Some rivers and smaller streams don’t make it far across the land. Instead, they form alluvial fans—broad, fan- or cone-shaped deposits of sediment that spread out where a river exits a narrow mountain canyon and spills onto a flat plain or wide valley floor.

As the stream emerges from the steep terrain, its velocity suddenly drops, and it loses the energy needed to carry its sediment load. The result is a dramatic unloading: gravel, sand, and silt cascade out in a spread that mimics the shape of a delta, but instead of reaching the sea, the water disperses inland.

Alluvial fans are particularly common in desert landscapes, but they also occur in temperate and alpine regions. In arid areas, deposition often happens rapidly, triggered by short-lived but intense rainstorms. These rare downpours mobilize more sediment than water, creating debris flows that charge down canyons and spread across the fan like an earthen flood.

Over time, streams on an alluvial fan shift and braid across the surface, constantly altering their course. Water gradually evaporates or infiltrates into the porous fan, never to be seen again on the surface. On larger fans, the sediment becomes sorted by grain size—coarse boulders and gravel lie near the mountain front, while finer sands and silts fan out further into the plain.

One of the best places to see this phenomenon is in the southwestern deserts of the United States, where alluvial fans paint the landscape with wide, pale arcs at the feet of rugged mountain ranges.

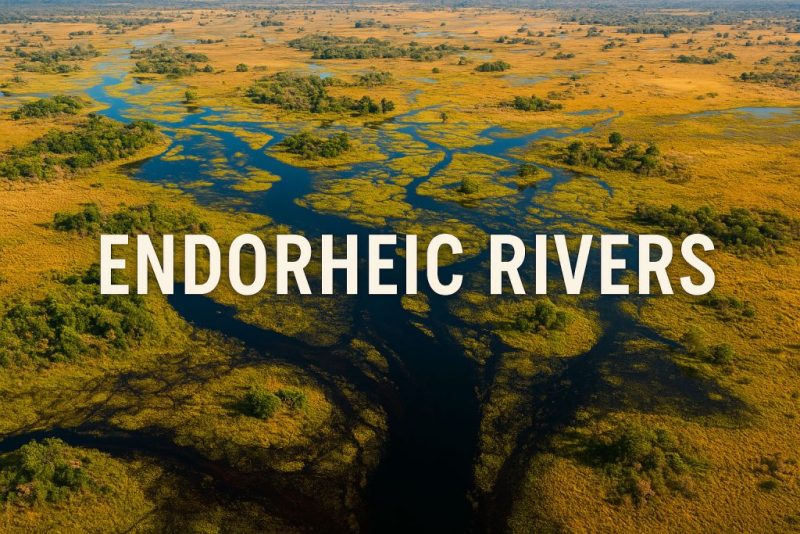

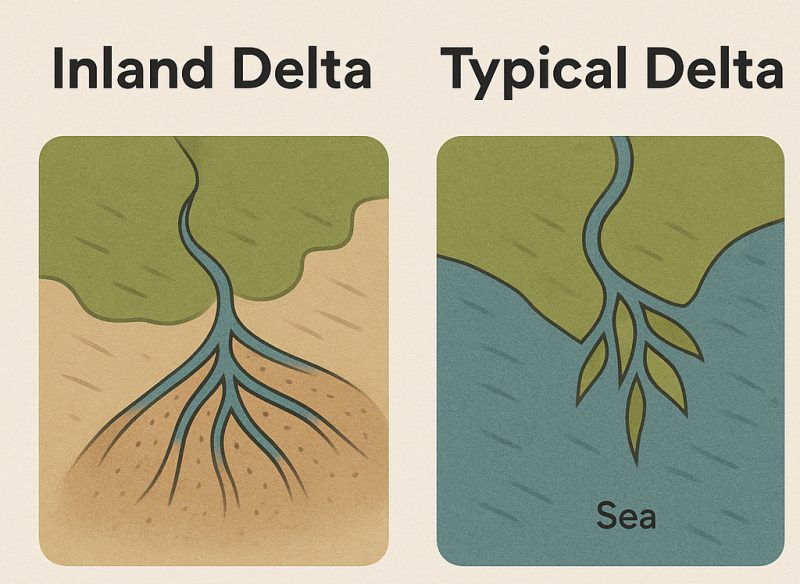

🌿 Inland Delta

The Okavango Delta in northwestern Botswana is perhaps the most iconic example of an inland delta, also known as a low-gradient alluvial fan or endorheic delta. Unlike most river deltas that spill into the sea, the Okavango empties into the sands of the Kalahari Basin, disappearing without ever reaching an ocean.

As the Okavango River slows and spreads, it splits into a complex web of braided channels, lagoons, and floodplains. This delta forms a mosaic of permanent marshes and seasonally inundated plains, with the river’s peak flood arriving during Botswana’s dry season—flooding vast swaths of the arid landscape and creating an improbable oasis in the heart of the desert.

Thanks to this seasonal miracle, the Okavango Delta is one of the most biologically rich wetlands on Earth. It supports a dazzling array of life, including some of the world’s most endangered large mammals: cheetahs, white and black rhinoceroses, African wild dogs, and lions roam this inland paradise.

Not all inland deltas are so large or ecologically complex. Some are little more than fanned-out river sediments that vanish into sandy basins or saline pans, their waters lost to evaporation or underground seepage. But each one tells a story of how rivers adapt when their journey ends far from the sea.

🏞️ Endorheic Lakes: Where the River Journey Ends

In the vast interior of continents, some rivers do not reach the sea at all. Instead, they flow into endorheic lakes—closed basins with no outlet to an ocean. These lakes are the final resting place for countless lost rivers, their waters trapped in isolation, evaporating under sun and sky.

Unlike typical lakes that overflow into rivers or drain to the sea, endorheic lakes are self-contained. They rise and fall with the seasons, and their water balance is controlled solely by inflow, evaporation, and seepage. Over millennia, this has made many of them salty or alkaline, as minerals accumulate with nowhere to escape.

Famous examples include:

- The Caspian Sea, technically the world’s largest endorheic lake, stretching across five countries and fed by the mighty Volga River.

- The Aral Sea, once among the largest lakes on Earth, now a cautionary tale of over-irrigation and ecological collapse.

- Lake Eyre in Australia, a shimmering salt pan most of the year, that occasionally transforms into a shallow inland sea after heavy rains.

- Lake Turkana in Kenya, the world’s largest desert lake, sustained by the Omo River yet threatened by damming upstream.

Endorheic lakes are often found in arid or semi-arid regions, where evaporation exceeds precipitation. They support unique ecosystems adapted to extreme salinity and fluctuating water levels. Some harbor endemic fish species or host vast gatherings of migratory birds—ephemeral sanctuaries surrounded by desert silence.

Yet, they are also vulnerable. Because they have no outlet, pollutants and agricultural runoff can accumulate over time, turning once-thriving habitats into toxic sinks. As climate shifts and human pressures grow, the fate of these ancient basins remains uncertain—mirrors of water at the edge of survival.

🌌 Lost Rivers: Flowing Through the Underground World

Some rivers seem to vanish from the face of the Earth—not by drying up or evaporating, but by slipping quietly into the ground. In landscapes dominated by porous limestone bedrock, known as karst, water doesn’t always stay on the surface. Instead, it carves secret paths through cracks, fissures, and caverns, flowing into the darkness below. These are the lost rivers.

Though invisible, their journey continues. Lost rivers dive underground, winding silently beneath forests, fields, and mountains. Far from being gone, their waters may reappear days or even weeks later—as a spring gushing from a cliffside, as a resurgence at the base of a hill, or even bubbling up from the seafloor as a freshwater submarine spring.

Some of these rivers reconnect with the surface and go on to join other rivers or reach the sea. Others remain elusive, never returning to the light. They flow endlessly through the subterranean world, weaving through caverns lined with mineral sculptures, echoing in halls where no sunlight has ever reached.

In Croatia, rivers like the Gacka, Lika, and Jadova are classic examples—disappearing into vast ponors (sinkholes) and reemerging far away, transformed but still alive. In other places, these underground streams may feed distant wells, wetlands, or even underwater springs in the ocean.

📚 Read more about the karst landscapes and the underground world of rivers in our dedicated feature.

🌧️ Rivers That Come and Go: Intermittent and Ephemeral Streams

Not all rivers flow year-round. In many regions—especially arid and semi-arid landscapes—some rivers appear only with the rains. These are known as intermittent and ephemeral rivers.

- Intermittent rivers flow seasonally, often during the wet months, and fall dry when the rains stop.

- Ephemeral rivers are even more fleeting—springing to life only after heavy storms, sometimes flowing for just hours or days before vanishing into sand and soil.

Though short-lived, these rivers play a vital role. They carve valleys, recharge aquifers, bring life to parched ecosystems, and carry nutrients across otherwise barren landscapes. Their flow is unpredictable, but when it comes, it transforms the land—filling dry channels, reviving vegetation, and calling wildlife to drink from waters that may soon be gone.

They are the rivers of absence and return, pulsing in rhythm with the sky.

Learn more about the rivers that vanish, reappear, and defy expectations.